Hauptinhalt

Results for

Me at the beginning of every meeting

Happy Pi Day!

3.14 π Day has arrived, and this post provides some very cool pi implementations and complete MATLAB code.

Firstly, in order to obtain the first n decimal places of pi, we need to write the following code (to prevent inaccuracies, we need to take a few more tails and perform another operation of taking the first n decimal places when needed):

function Pi=getPi(n)

if nargin<1,n=3;end

Pi=char(vpa(sym(pi),n+10));

Pi=abs(Pi)-48;

Pi=Pi(3:n+2);

end

With this function to obtain the decimal places of pi, our visualization journey has begun~Step by step, from simple to complex~(Please try to use newer versions of MATLAB to run, at least R17b)

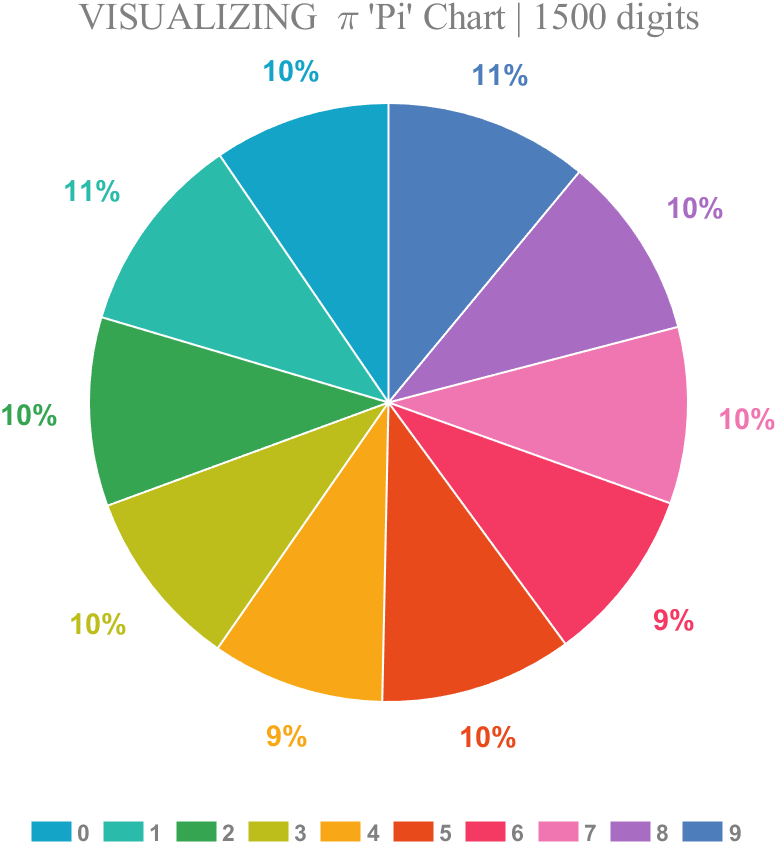

1 Pie chart

Just calculate the proportion of each digit to the first 1500 decimal places:

% 获取pi前1500位小数

Pi=getPi(1500);

% 统计各个数字出现次数

numNum=find([diff(sort(Pi)),1]);

numNum=[numNum(1),diff(numNum)];

% 配色列表

CM=[20,164,199;43,187,170;53,165,81;189,190,28;248,167,22;

232,74,27;244,57,99;240,118,177;168,109,195;78,125,187]./255;

% 绘图并修饰

pieHdl=pie(numNum);

set(gcf,'Color',[1,1,1],'Position',[200,100,620,620]);

for i=1:2:20

pieHdl(i).EdgeColor=[1,1,1];

pieHdl(i).LineWidth=1;

pieHdl(i).FaceColor=CM((i+1)/2,:);

end

for i=2:2:20

pieHdl(i).Color=CM(i/2,:);

pieHdl(i).FontWeight='bold';

pieHdl(i).FontSize=14;

end

% 绘制图例并修饰

lgdHdl=legend(num2cell('0123456789'));

lgdHdl.FontWeight='bold';

lgdHdl.FontSize=11;

lgdHdl.TextColor=[.5,.5,.5];

lgdHdl.Location='southoutside';

lgdHdl.Box='off';

lgdHdl.NumColumns=10;

lgdHdl.ItemTokenSize=[20,15];

title("VISUALIZING \pi 'Pi' Chart | 1500 digits",'FontSize',18,...

'FontName','Times New Roman','Color',[.5,.5,.5])

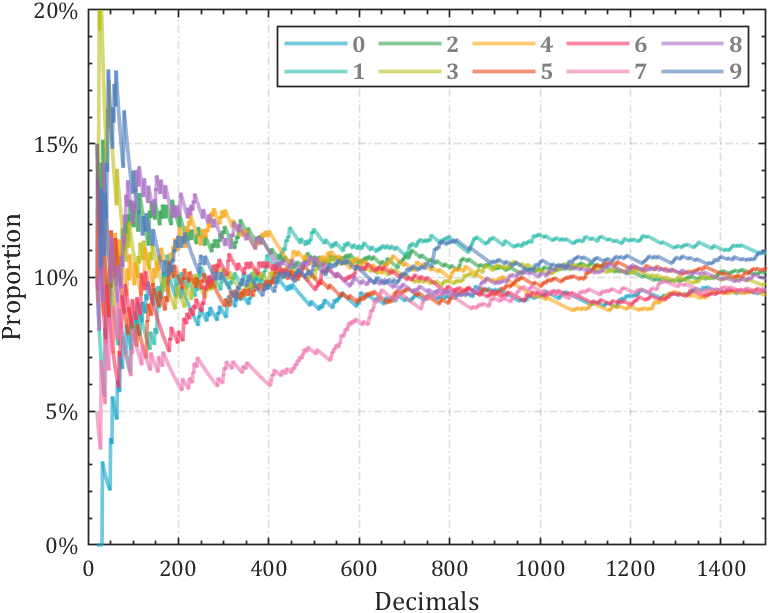

2 line chart

Calculate the change in the proportion of each number:

% 获取pi前1500位小数

Pi=getPi(1500);

% 计算比例变化

Ratio=cumsum(Pi==(0:9)',2);

Ratio=Ratio./sum(Ratio);

D=1:length(Ratio);

% 配色列表

CM=[20,164,199;43,187,170;53,165,81;189,190,28;248,167,22;

232,74,27;244,57,99;240,118,177;168,109,195;78,125,187]./255;

hold on

% 循环绘图

for i=1:10

plot(D(20:end),Ratio(i,20:end),'Color',[CM(i,:),.6],'LineWidth',1.8)

end

% 坐标区域修饰

ax=gca;box on;grid on

ax.YLim=[0,.2];

ax.YTick=0:.05:.2;

ax.XTick=0:200:1400;

ax.YTickLabel={'0%','5%','10%','15%','20%'};

ax.XMinorTick='on';

ax.YMinorTick='on';

ax.LineWidth=.8;

ax.GridLineStyle='-.';

ax.FontName='Cambria';

ax.FontSize=11;

ax.XLabel.String='Decimals';

ax.YLabel.String='Proportion';

ax.XLabel.FontSize=13;

ax.YLabel.FontSize=13;

% 绘制图例并修饰

lgdHdl=legend(num2cell('0123456789'));

lgdHdl.NumColumns=5;

lgdHdl.FontWeight='bold';

lgdHdl.FontSize=11;

lgdHdl.TextColor=[.5,.5,.5];

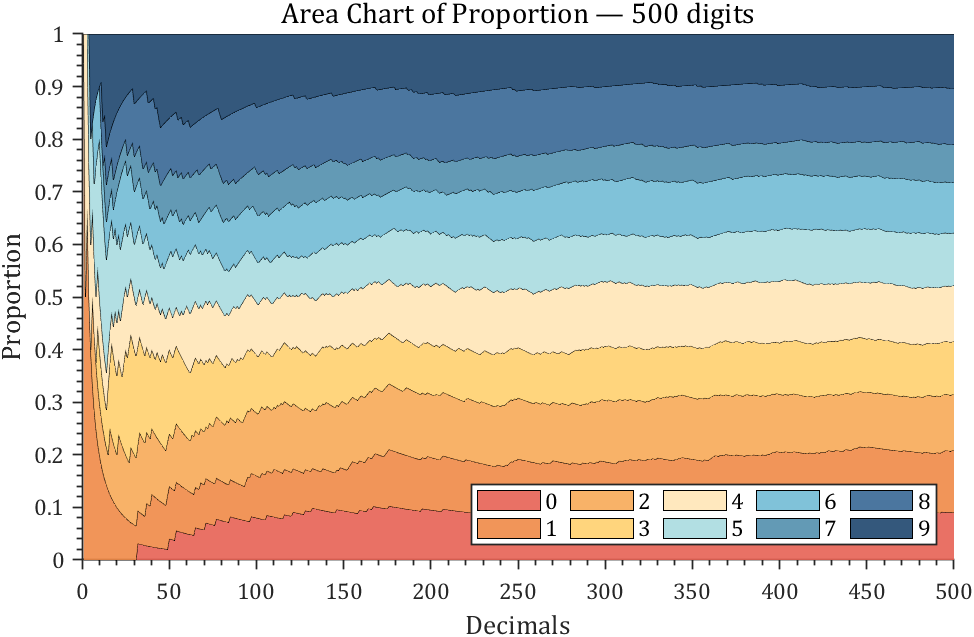

3 stacked area diagram

% 获取pi前500位小数

Pi=getPi(500);

% 计算比例变化

Ratio=cumsum(Pi==(0:9)',2);

Ratio=Ratio./sum(Ratio);

% 配色列表

CM=[231,98,84;239,138,71;247,170,88;255,208,111;255,230,183;

170,220,224;114,188,213;82,143,173;55,103,149;30,70,110]./255;

% 绘制堆叠面积图

hold on

areaHdl=area(Ratio');

for i=1:10

areaHdl(i).FaceColor=CM(i,:);

areaHdl(i).FaceAlpha=.9;

end

% 图窗和坐标区域修饰

set(gcf,'Position',[200,100,720,420]);

ax=gca;

ax.YLim=[0,1];

ax.XMinorTick='on';

ax.YMinorTick='on';

ax.LineWidth=.8;

ax.FontName='Cambria';

ax.FontSize=11;

ax.TickDir='out';

ax.XLabel.String='Decimals';

ax.YLabel.String='Proportion';

ax.XLabel.FontSize=13;

ax.YLabel.FontSize=13;

ax.Title.String='Area Chart of Proportion — 500 digits';

ax.Title.FontSize=14;

% 绘制图例并修饰

lgdHdl=legend(num2cell('0123456789'));

lgdHdl.NumColumns=5;

lgdHdl.FontSize=11;

lgdHdl.Location='southeast';

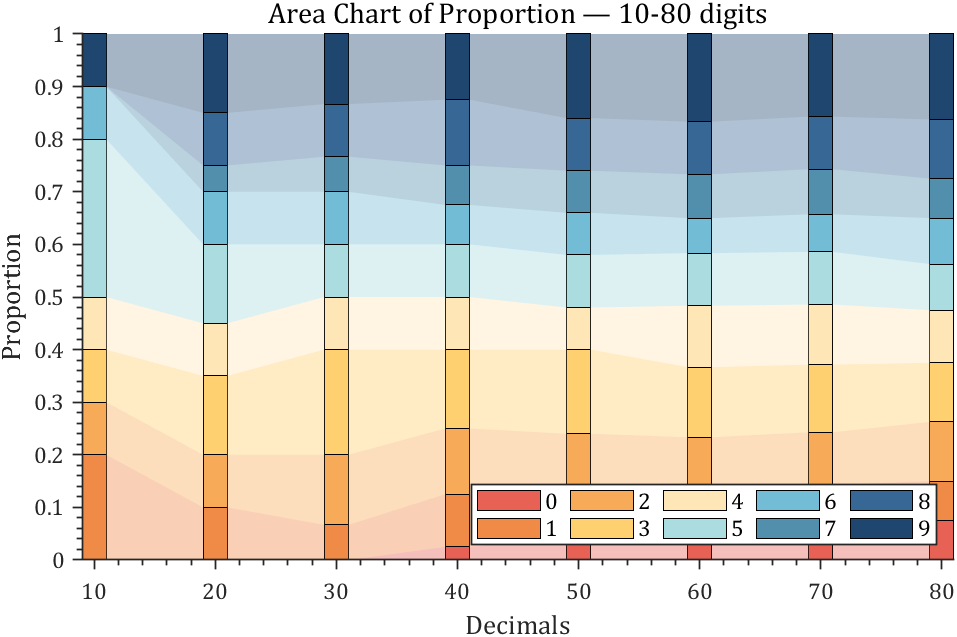

4 connected stacked bar chart

% 获取pi前100位小数

Pi=getPi(100);

% 计算比例变化

Ratio=cumsum(Pi==(0:9)',2);

Ratio=Ratio./sum(Ratio);

X=Ratio(:,10:10:80)';

barHdl=bar(X,'stacked','BarWidth',.2);

CM=[231,98,84;239,138,71;247,170,88;255,208,111;255,230,183;

170,220,224;114,188,213;82,143,173;55,103,149;30,70,110]./255;

for i=1:10

barHdl(i).FaceColor=CM(i,:);

end

% 以下是生成连接的部分

hold on;axis tight

yEndPoints=reshape([barHdl.YEndPoints]',length(barHdl(1).YData),[])';

zeros(1,length(barHdl(1).YData));

yEndPoints=[zeros(1,length(barHdl(1).YData));yEndPoints];

barWidth=barHdl(1).BarWidth;

for i=1:length(barHdl)

for j=1:length(barHdl(1).YData)-1

y1=min(yEndPoints(i,j),yEndPoints(i+1,j));

y2=max(yEndPoints(i,j),yEndPoints(i+1,j));

if y1*y2<0

ty=yEndPoints(find(yEndPoints(i+1,j)*yEndPoints(1:i,j)>=0,1,'last'),j);

y1=min(ty,yEndPoints(i+1,j));

y2=max(ty,yEndPoints(i+1,j));

end

y3=min(yEndPoints(i,j+1),yEndPoints(i+1,j+1));

y4=max(yEndPoints(i,j+1),yEndPoints(i+1,j+1));

if y3*y4<0

ty=yEndPoints(find(yEndPoints(i+1,j+1)*yEndPoints(1:i,j+1)>=0,1,'last'),j+1);

y3=min(ty,yEndPoints(i+1,j+1));

y4=max(ty,yEndPoints(i+1,j+1));

end

fill([j+.5.*barWidth,j+1-.5.*barWidth,j+1-.5.*barWidth,j+.5.*barWidth],...

[y1,y3,y4,y2],barHdl(i).FaceColor,'FaceAlpha',.4,'EdgeColor','none');

end

end

% 图窗和坐标区域修饰

set(gcf,'Position',[200,100,720,420]);

ax=gca;box off

ax.YLim=[0,1];

ax.XMinorTick='on';

ax.YMinorTick='on';

ax.LineWidth=.8;

ax.FontName='Cambria';

ax.FontSize=11;

ax.TickDir='out';

ax.XTickLabel={'10','20','30','40','50','60','70','80'};

ax.XLabel.String='Decimals';

ax.YLabel.String='Proportion';

ax.XLabel.FontSize=13;

ax.YLabel.FontSize=13;

ax.Title.String='Area Chart of Proportion — 10-80 digits';

ax.Title.FontSize=14;

% 绘制图例并修饰

lgdHdl=legend(barHdl,num2cell('0123456789'));

lgdHdl.NumColumns=5;

lgdHdl.FontSize=11;

lgdHdl.Location='southeast';

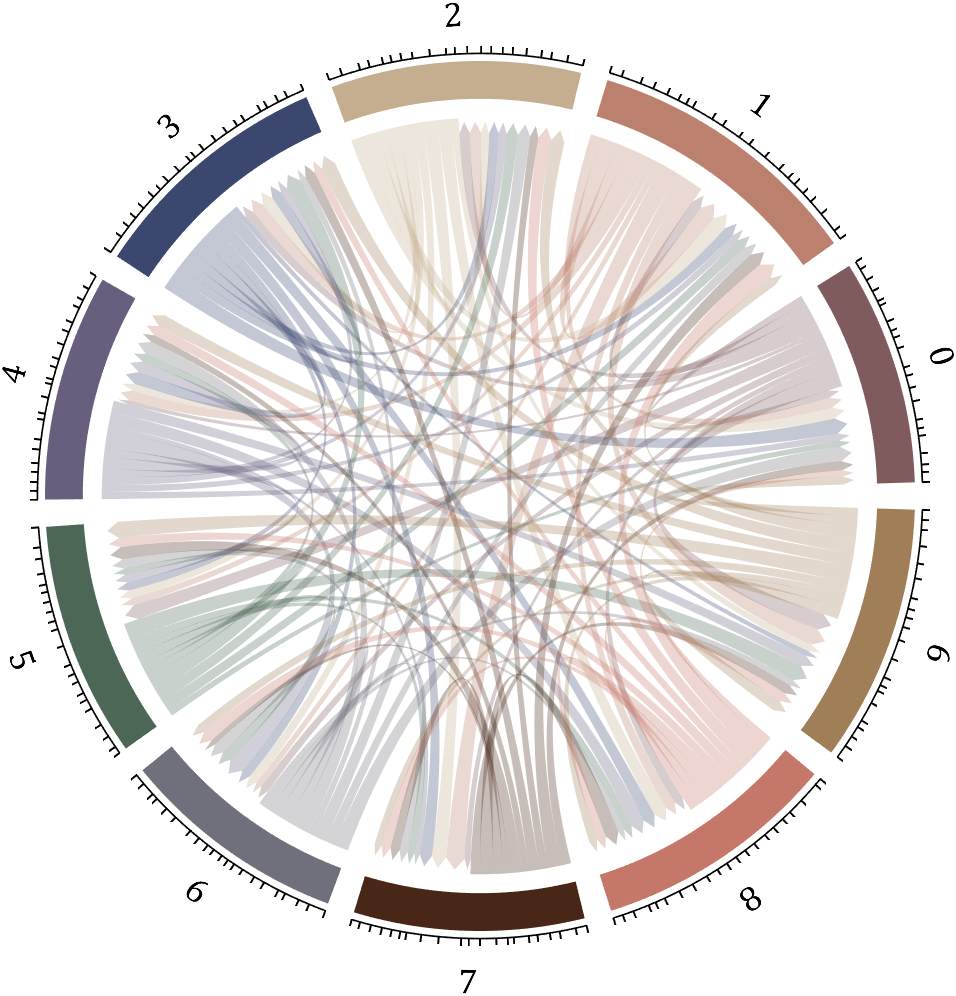

5 bichord chart

Need to use this tool:

% 构建连接矩阵

dataMat=zeros(10,10);

Pi=getPi(1001);

for i=1:1000

dataMat(Pi(i)+1,Pi(i+1)+1)=dataMat(Pi(i)+1,Pi(i+1)+1)+1;

end

BCC=biChordChart(dataMat,'Arrow','on','Label',num2cell('0123456789'));

BCC=BCC.draw();

% 添加刻度

BCC.tickState('on')

% 修改字体,字号及颜色

BCC.setFont('FontName','Cambria','FontSize',17)

set(gcf,'Position',[200,100,820,820]);

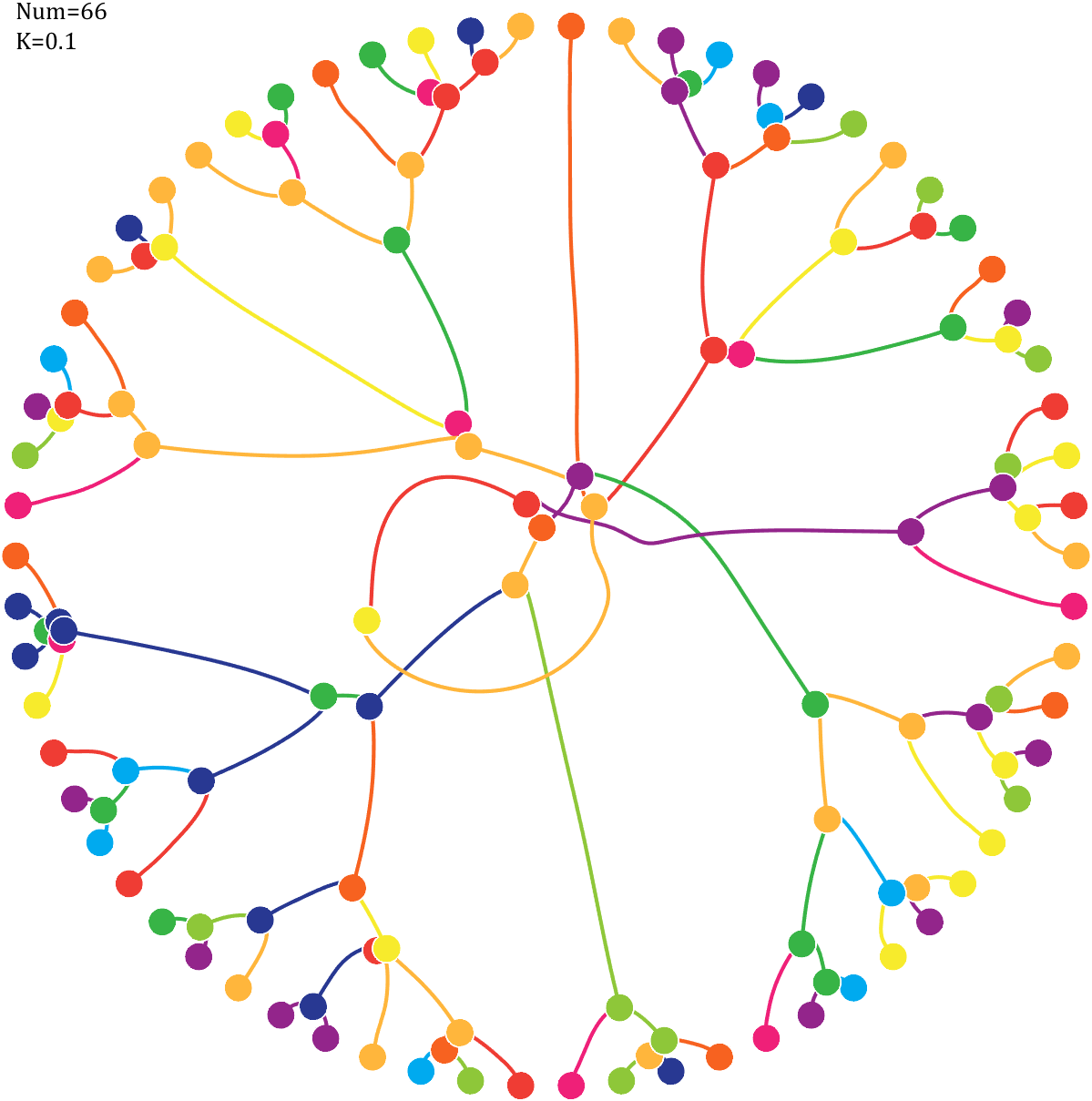

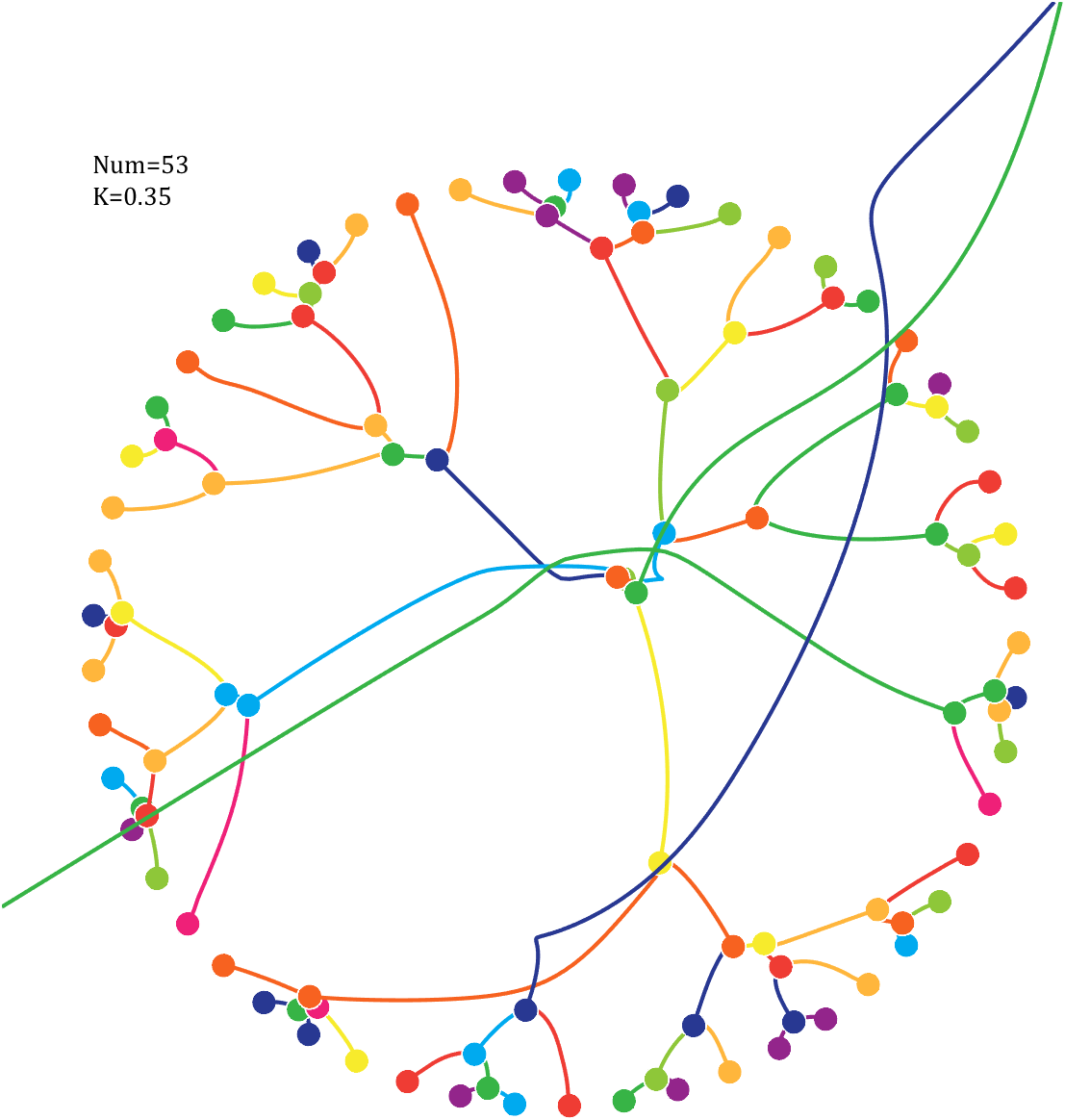

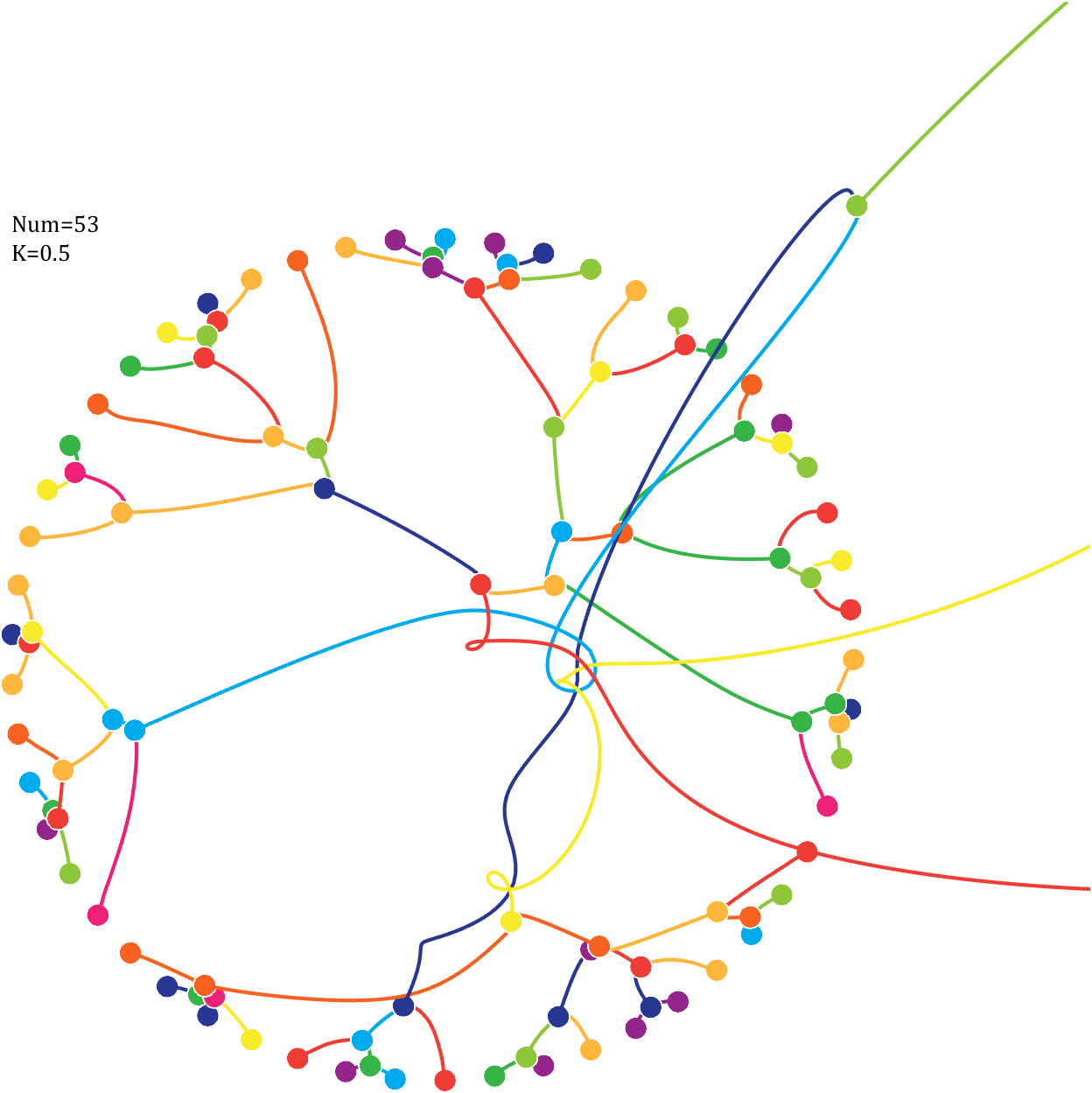

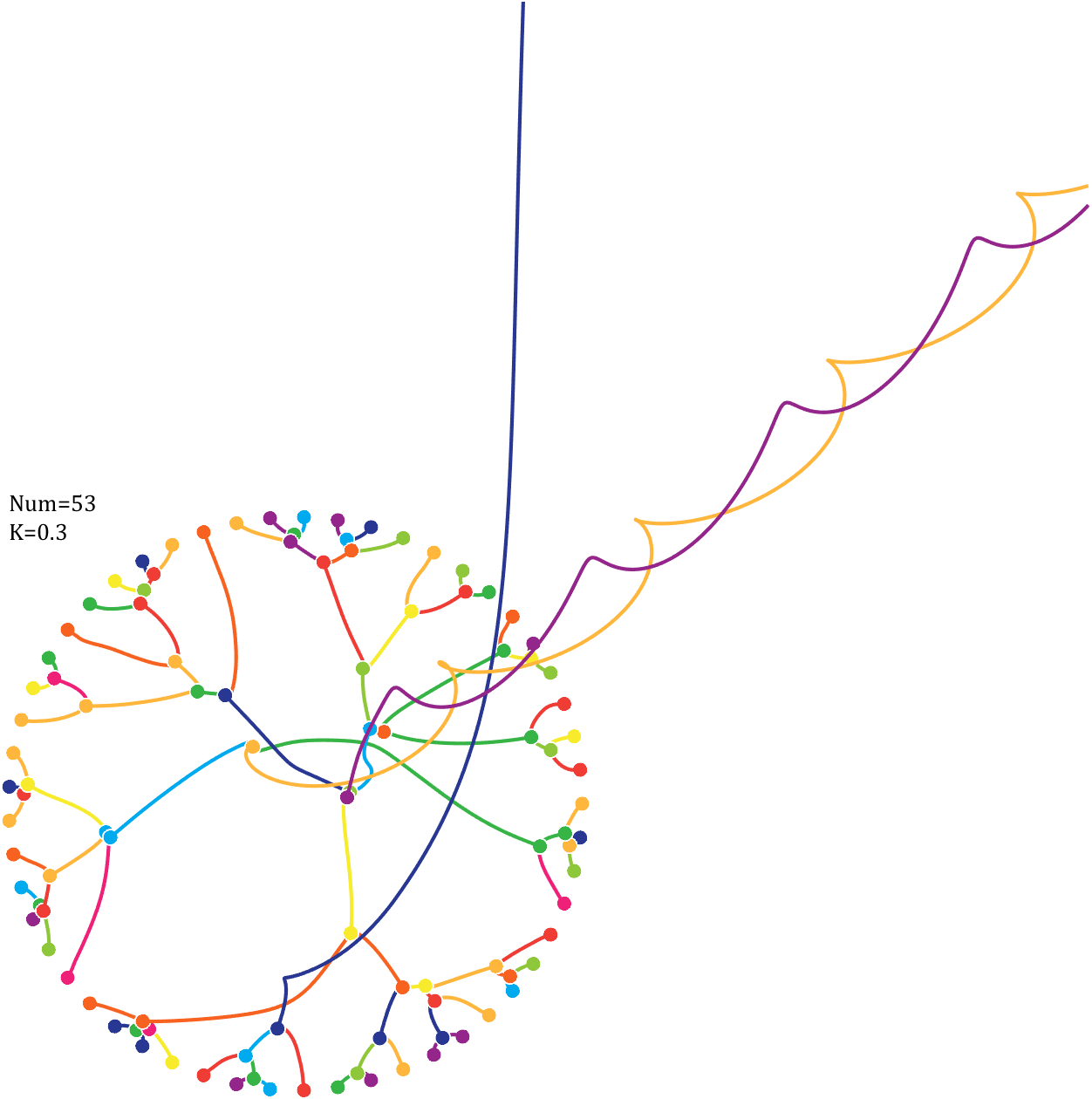

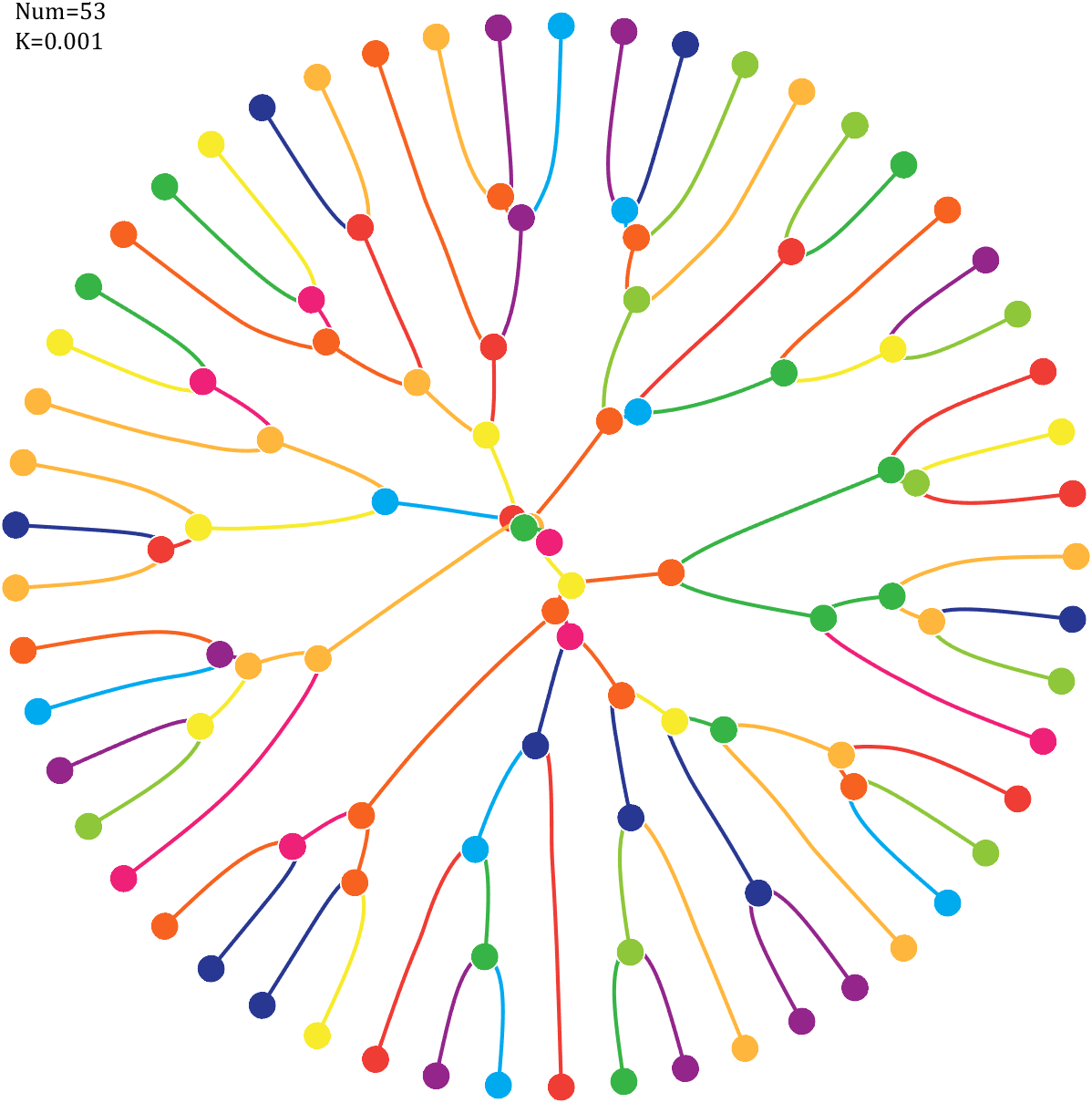

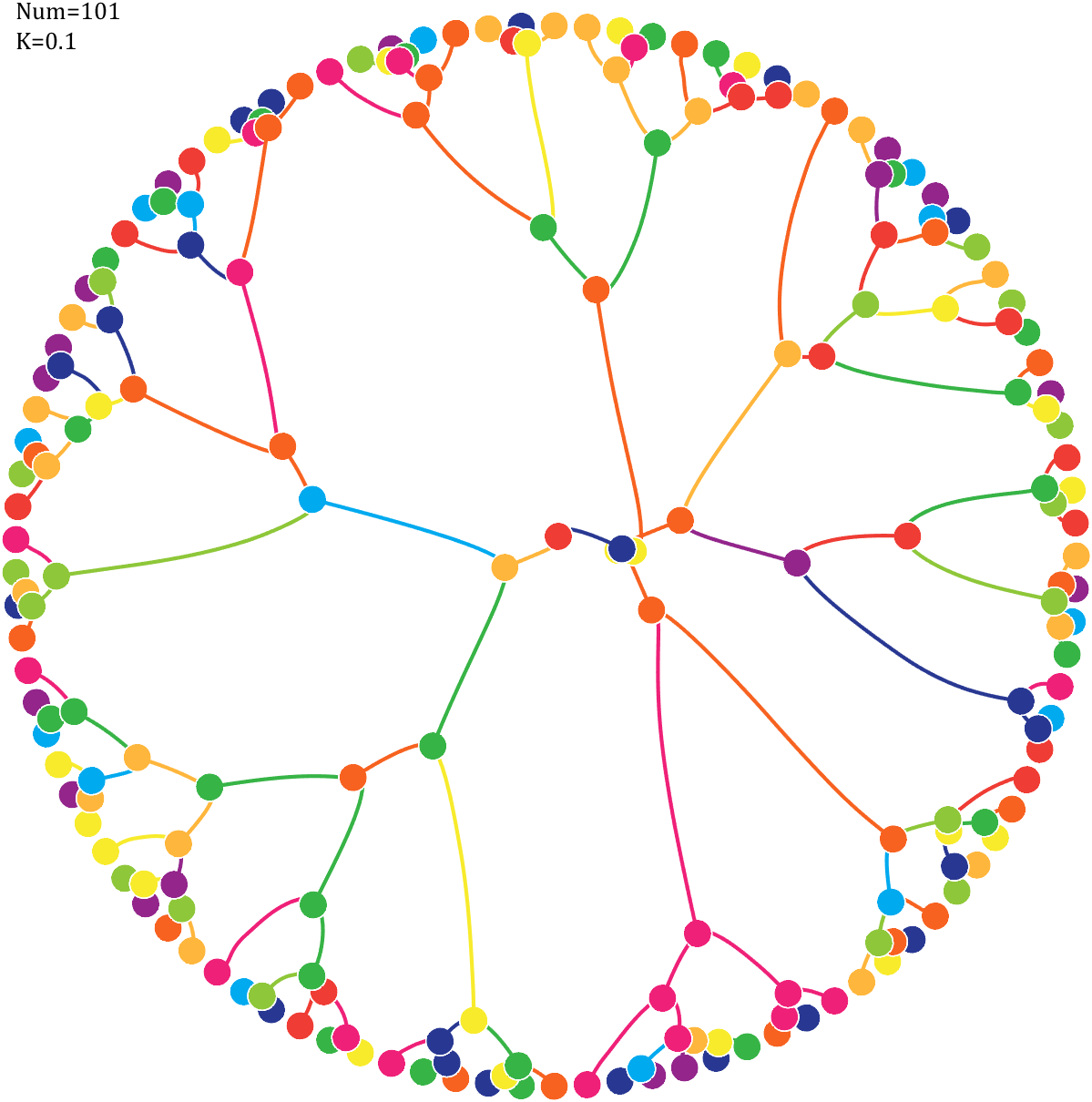

6 Gravity simulation diagram

Imagine each decimal as a small ball with a mass of

For example, if , the weight of ball 0 is 1, ball 9 is 1.2589, the initial velocity of the ball is 0, and it is attracted by other balls. Gravity follows the inverse square law, and if the balls are close enough, they will collide and their value will become

, the weight of ball 0 is 1, ball 9 is 1.2589, the initial velocity of the ball is 0, and it is attracted by other balls. Gravity follows the inverse square law, and if the balls are close enough, they will collide and their value will become

After adding, take the mod, add the velocity direction proportionally, and recalculate the weight.

Pi=[3,getPi(71)];K=.18;

% 基础配置

CM=[239,32,120;239,60,52;247,98,32;255,182,60;247,235,44;

142,199,57;55,180,70;0,170,239;40,56,146;147,37,139]./255;

T=linspace(0,2*pi,length(Pi)+1)';

T=T(1:end-1);

ct=linspace(0,2*pi,100);

cx=cos(ct).*.027;

cy=sin(ct).*.027;

% 初始数据

Pi=Pi(:);

N=Pi;

X=cos(T);Y=sin(T);

VX=T.*0;VY=T.*0;

PX=X;PY=Y;

% 未碰撞时初始质量

getM=@(x)(x+1).^K;

M=getM(N);

% 绘制初始圆圈

hold on

for i=1:length(N)

fill(cx+X(i),cy+Y(i),CM(N(i)+1,:),'EdgeColor','w','LineWidth',1)

end

for k=1:800

% 计算加速度

Rn2=1./squareform(pdist([X,Y])).^2;

Rn2(eye(length(X))==1)=0;

MRn2=Rn2.*(M');

AX=X'-X;AY=Y'-Y;

normXY=sqrt(AX.^2+AY.^2);

AX=AX./normXY;AX(eye(length(X))==1)=0;

AY=AY./normXY;AY(eye(length(X))==1)=0;

AX=sum(AX.*MRn2,2)./150000;

AY=sum(AY.*MRn2,2)./150000;

% 计算速度及新位置

VX=VX+AX;X=X+VX;PX=[PX,X];

VY=VY+AY;Y=Y+VY;PY=[PY,Y];

% 检测是否有碰撞

R=squareform(pdist([X,Y]));

R(triu(ones(length(X)))==1)=inf;

[row,col]=find(R<=0.04);

if length(X)==1

break;

end

if ~isempty(row)

% 碰撞的点合为一体

XC=(X(row)+X(col))./2;YC=(Y(row)+Y(col))./2;

VXC=(VX(row).*M(row)+VX(col).*M(col))./(M(row)+M(col));

VYC=(VY(row).*M(row)+VY(col).*M(col))./(M(row)+M(col));

PC=nan(length(row),size(PX,2));

NC=mod(N(row)+N(col),10);

% 删除碰撞点并绘图

uniNum=unique([row;col]);

X(uniNum)=[];VX(uniNum)=[];

Y(uniNum)=[];VY(uniNum)=[];

for i=1:length(uniNum)

plot(PX(uniNum(i),:),PY(uniNum(i),:),'LineWidth',2,'Color',CM(N(uniNum(i))+1,:))

end

PX(uniNum,:)=[];PY(uniNum,:)=[];N(uniNum,:)=[];

% 绘制圆形

for i=1:length(XC)

fill(cx+XC(i),cy+YC(i),CM(NC(i)+1,:),'EdgeColor','w','LineWidth',1)

end

% 补充合体点

X=[X;XC];Y=[Y;YC];VX=[VX;VXC];VY=[VY;VYC];

PX=[PX;PC];PY=[PY;PC];N=[N;NC];M=getM(N);

end

end

for i=1:size(PX,1)

plot(PX(i,:),PY(i,:),'LineWidth',2,'Color',CM(N(i)+1,:))

end

text(-1,1,{['Num=',num2str(length(Pi))];['K=',num2str(K)]},'FontSize',13,'FontName','Cambria')

% 图窗及坐标区域修饰

set(gcf,'Position',[200,100,820,820]);

ax=gca;

ax.Position=[0,0,1,1];

ax.DataAspectRatio=[1,1,1];

ax.XLim=[-1.1,1.1];

ax.YLim=[-1.1,1.1];

ax.XTick=[];

ax.YTick=[];

ax.XColor='none';

ax.YColor='none';

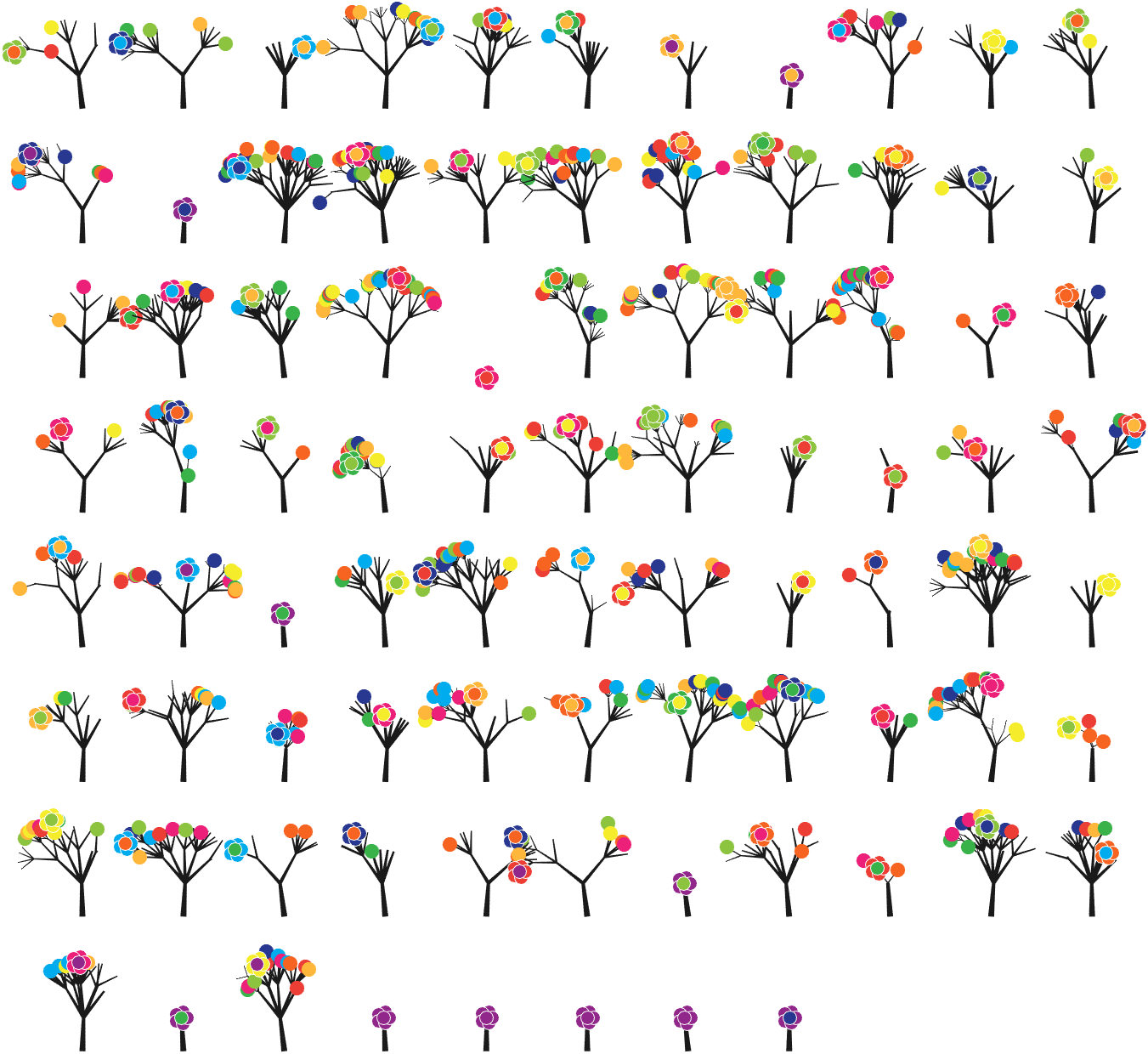

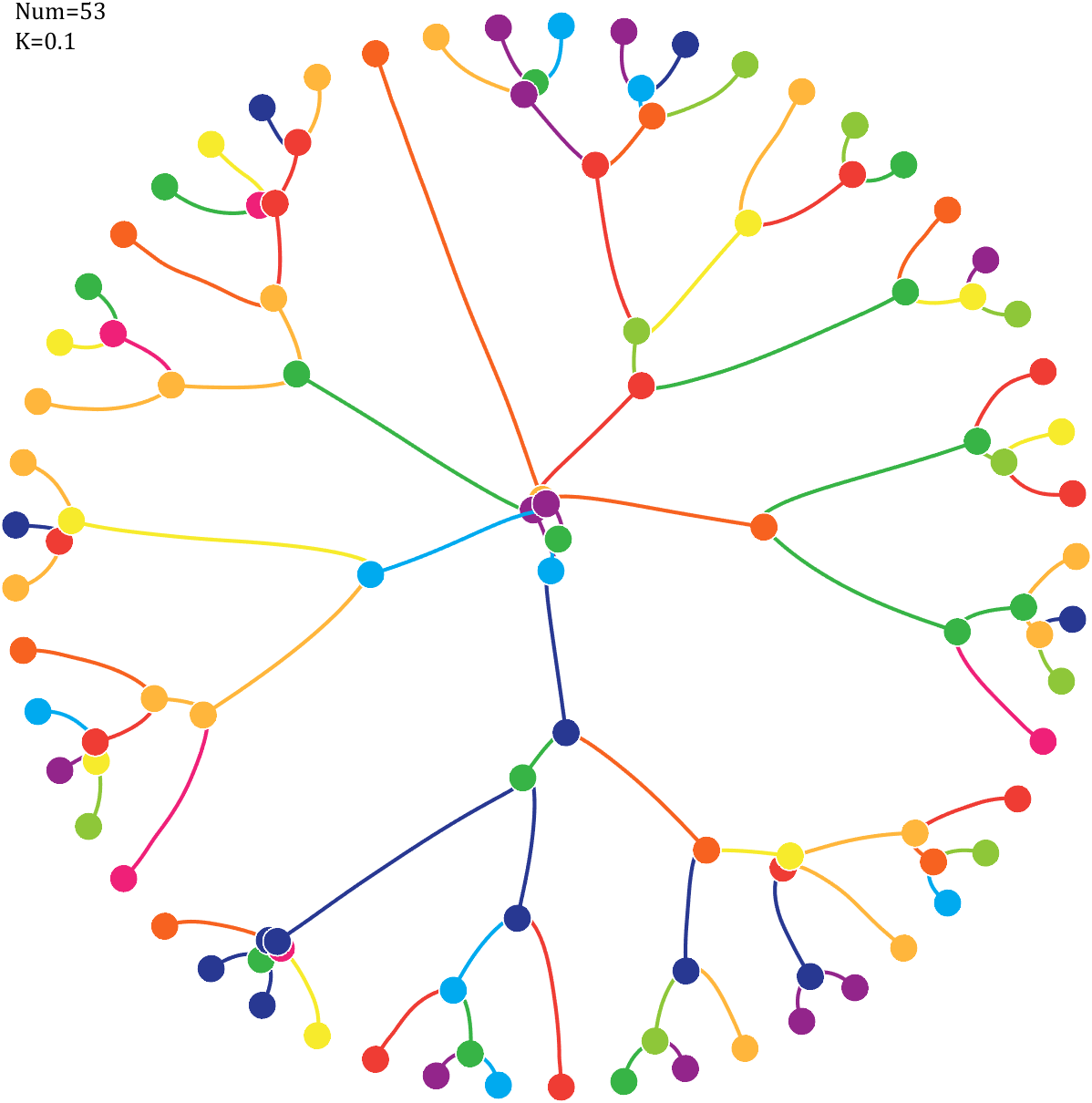

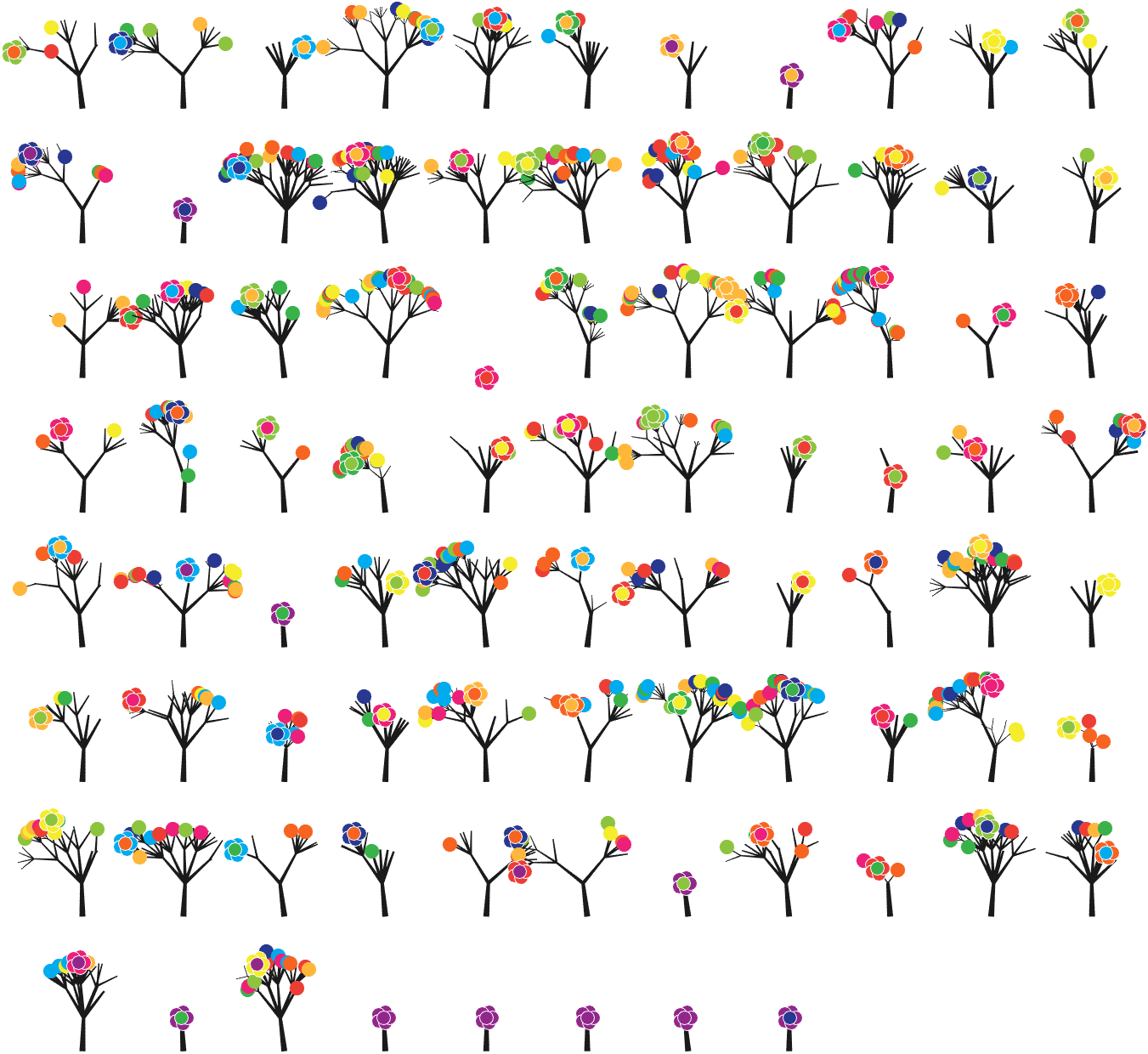

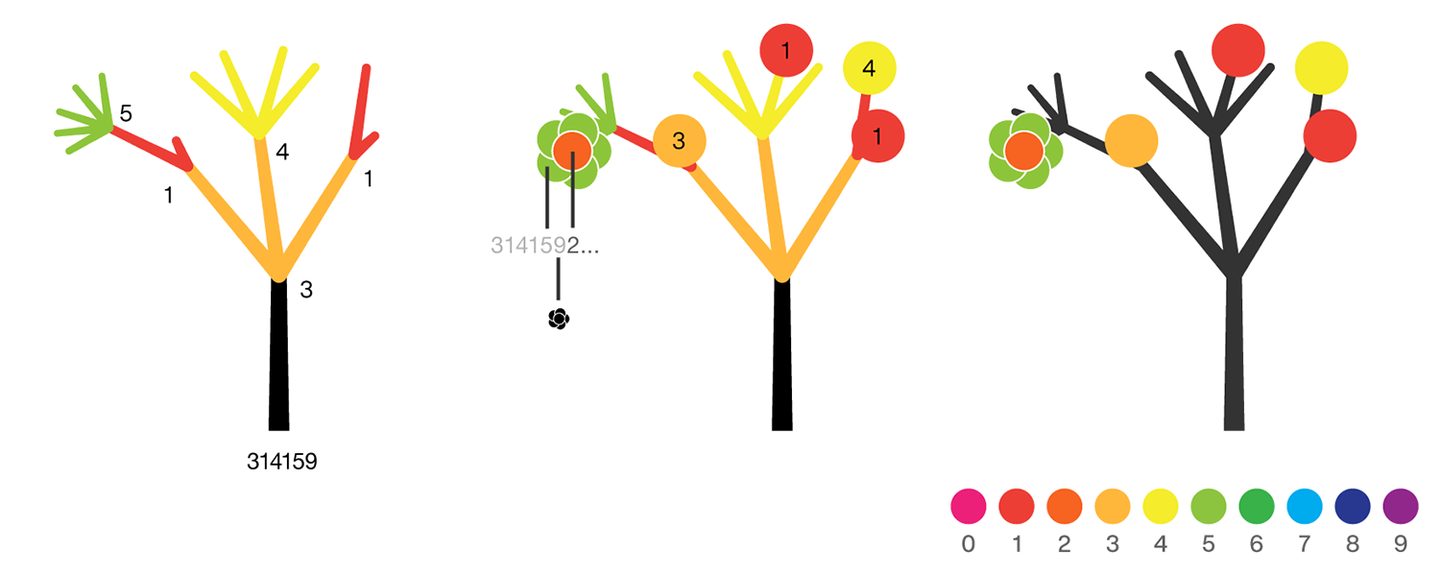

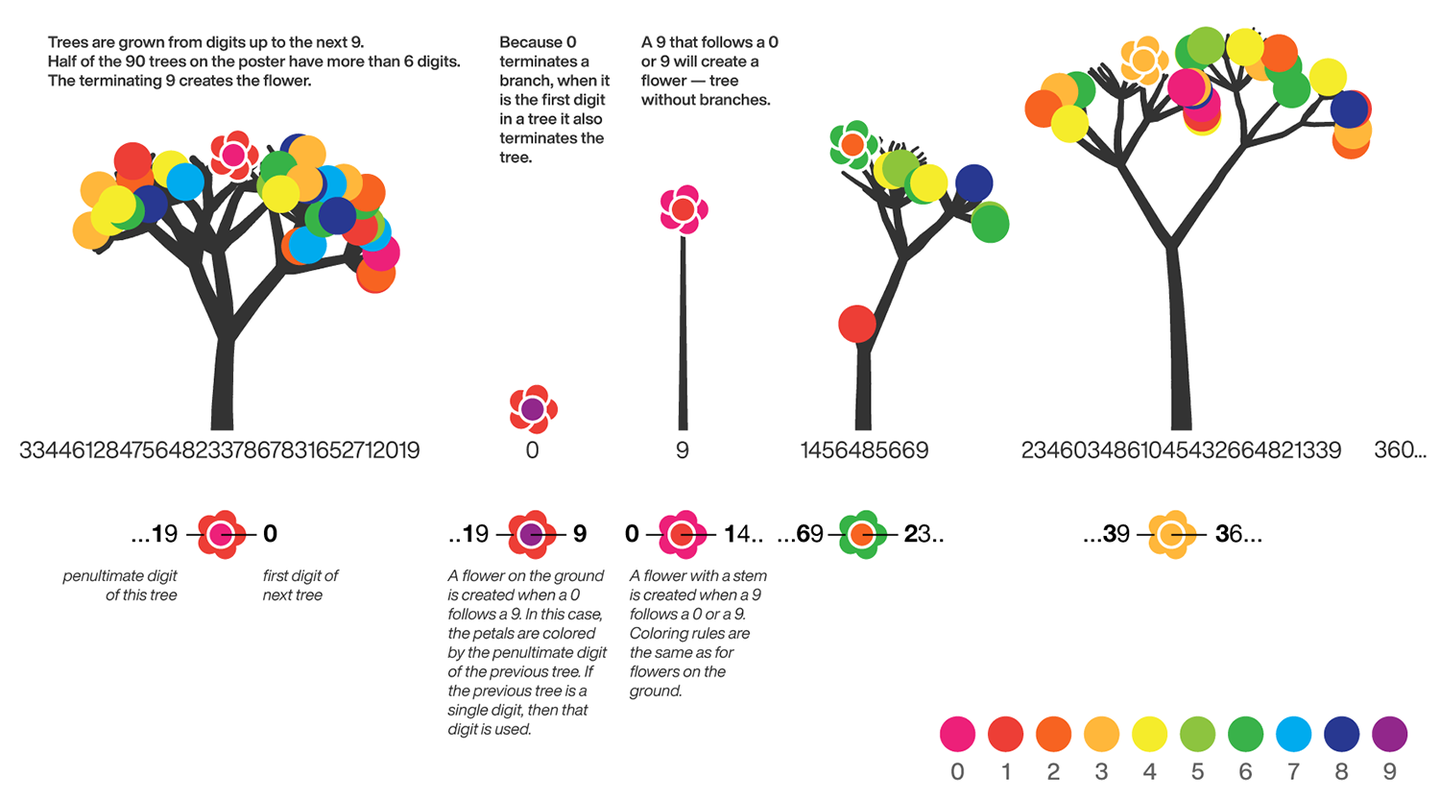

7 forest chart

The method comes from

The digits of π are shown as a forest. Each tree in the forest represents the digits of π up to the next 9. The first 10 trees are "grown" from the digit sets 314159, 2653589, 79, 3238462643383279, 50288419, 7169, 39, 9, 3751058209, and 749.

BRANCHES

The first digit of a tree controls how many branches grow from the trunk of the tree. For example, the first tree's first digit is 3, so you see 3 branches growing from the trunk.

The next digit's branches grow from the end of a branch of the previous digit in left-to-right order. This process continues until all the tree's digits have been used up.

Each tree grows from a set of consecutive digits sampled from the digits of π up to the next 9. The first tree, shown here, grows from 314159. Each of the digits determine how many branches grow at each fork in the tree — the branches here are colored by their corresponding digit to illustrate this. Leaves encode the digits in a left-to-right order. The digit 9 spawns a flower on one of the branches of the previous digit. The branching exception is 0, which terminates the current branch — 0 branches grow!

LEAVES AND FLOWERS

The tree's digits themselves are drawn as circular leaves, color-coded by the digit.

The leaf exception is 9, which causes one of the branches of the previous digit to sprout a flower! The petals of the flower are colored by the digit before the 9 and the center is colored by the digit after the 9, which is on the next tree. This is how the forest propagates.

The colors of a flower are determined by the first digit of the next tree and the penultimate digit of the current tree. If the current tree only has one digit, then that digit is used. Leaves are placed at the tips of branches in a left-to-right order — you can "easily" read them off. Additionally, the leaves are distributed within the tree (without disturbing their left-to-right order) to spread them out as much as possible and avoid overlap. This order is deterministic.

The leaf placement exception are the branch set that sprouted the flower. These are not used to grow leaves — the flower needs space!

function PiTree(X,pos,D)

lw=2;

theta=pi/2+(rand(1)-.5).*pi./12;

% 树叶及花朵颜色

CM=[237,32,121;237,62,54;247,99,33;255,183,59;245,236,43;

141,196,63;57,178,74;0,171,238;40,56,145;146,39,139]./255;

hold on

if all(X(1:end-2)==0)

endSet=[pos,pos,theta];

else

kplot(pos(1)+[0,cos(theta)],pos(2)+[0,sin(theta)],lw./.6)

endSet=[pos,pos+[cos(theta),sin(theta)],theta];

% 计算层级

Layer=0;

for i=1:length(X)

Layer=[Layer,ones(1,X(i)).*i];

end

% 计算树枝

if D

for i=1:length(X)-2

if X(i)==0 % 若数值为0则不长树枝

newSet=endSet(1,:);

elseif X(i)==1 % 若数值为1则一长一短两个树枝

tTheta=endSet(1,5);

tTheta=linspace(tTheta+pi/8,tTheta-pi/8,2)'+(rand([2,1])-.5).*pi./8;

newSet=repmat(endSet(1,3:4),[X(i),1]);

newSet=[newSet.*[1;1],newSet+[cos(tTheta),sin(tTheta)].*.7^Layer(i).*[1;.1],tTheta];

else % 其他情况数值为几长几个树枝

tTheta=endSet(1,5);

tTheta=linspace(tTheta+pi/5,tTheta-pi/5,X(i))'+(rand([X(i),1])-.5).*pi./8;

newSet=repmat(endSet(1,3:4),[X(i),1]);

newSet=[newSet,newSet+[cos(tTheta),sin(tTheta)].*.7^Layer(i),tTheta];

end

% 绘制树枝

for j=1:size(newSet,1)

kplot(newSet(j,[1,3]),newSet(j,[2,4]),lw.*.6^Layer(i))

end

endSet=[endSet;newSet];

endSet(1,:)=[];

end

end

end

% 计算叶子和花朵位置

FLSet=endSet(:,3:4);

[~,FLInd]=sort(FLSet(:,1));

FLSet=FLSet(FLInd,:);

[~,tempInd]=sort(rand([1,size(FLSet,1)]));

tempInd=sort(tempInd(1:length(X)-2));

flowerInd=tempInd(randi([1,length(X)-2],[1,1]));

leafInd=tempInd(tempInd~=flowerInd);

% 绘制树叶

for i=1:length(leafInd)

scatter(FLSet(leafInd(i),1),FLSet(leafInd(i),2),70,'filled','CData',CM(X(i)+1,:))

end

% 绘制花朵

for i=1:5

% if ~D

% tC=CM(X(end)+1,:);

% else

% tC=CM(X(end-2)+1,:);

% end

scatter(FLSet(flowerInd,1)+cos(pi*2*i/5).*.18,FLSet(flowerInd,2)+sin(pi*2*i/5).*.18,60,...

'filled','CData',CM(X(end-2)+1,:),'MarkerEdgeColor',[1,1,1])

end

scatter(FLSet(flowerInd,1),FLSet(flowerInd,2),60,'filled','CData',CM(X(end)+1,:),'MarkerEdgeColor',[1,1,1])

drawnow;%axis tight

% =========================================================================

function kplot(XX,YY,LW,varargin)

LW=linspace(LW,LW*.6,10);%+rand(1,20).*LW./10;

XX=linspace(XX(1),XX(2),11)';

XX=[XX(1:end-1),XX(2:end)];

YY=linspace(YY(1),YY(2),11)';

YY=[YY(1:end-1),YY(2:end)];

for ii=1:10

plot(XX(ii,:),YY(ii,:),'LineWidth',LW(ii),'Color',[.1,.1,.1])

end

end

end

main part:

Pi=[3,getPi(800)];

pos9=[0,find(Pi==9)];

set(gcf,'Position',[200,50,900,900],'Color',[1,1,1]);

ax=gca;hold on

ax.Position=[0,0,1,1];

ax.DataAspectRatio=[1,1,1];

ax.XLim=[.5,36];

ax.XTick=[];

ax.YTick=[];

ax.XColor='none';

ax.YColor='none';

for j=1:8

for i=1:11

n=i+(j-1)*11;

if n<=85

tPi=Pi((pos9(n)+1):pos9(n+1)+1);

if length(tPi)>2

PiTree(tPi,[0+i*3,0-j*4],true);

else

PiTree([Pi(pos9(n)),tPi],[0+i*3,0-j*4],false);

end

end

end

end

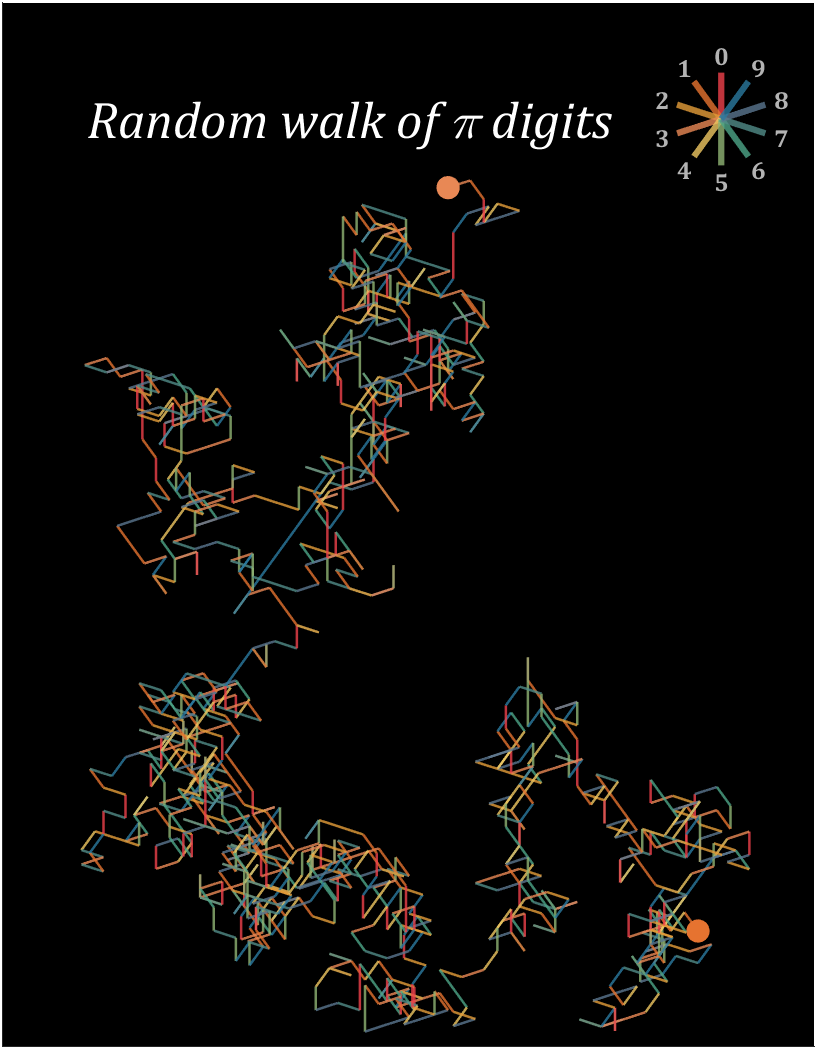

8 random walk

n=1200;

% 获取pi前n位小数

Pi=getPi(n);

CM=[239,65,75;230,115,48;229,158,57;232,136,85;239,199,97;

144,180,116;78,166,136;81,140,136;90,118,142;43,121,159]./255;

hold on

endPoint=[0,0];

t=linspace(0,2*pi,100);

T=linspace(0,2*pi,11)+pi/2;

fill(endPoint(1)+cos(t).*.5,endPoint(2)+sin(t).*.5,CM(Pi(1)+1,:),'EdgeColor','none')

for i=1:n

theta=T(Pi(i)+1);

plot(endPoint(1)+[0,cos(theta)],endPoint(2)+[0,sin(theta)],'Color',[CM(Pi(i)+1,:),.8],'LineWidth',1.2);

endPoint=endPoint+[cos(theta),sin(theta)];

end

fill(endPoint(1)+cos(t).*.5,endPoint(2)+sin(t).*.5,CM(Pi(n)+1,:),'EdgeColor','none')

% 图窗和坐标区域修饰

set(gcf,'Position',[200,100,820,820]);

ax=gca;

ax.XTick=[];

ax.YTick=[];

ax.Color=[0,0,0];

ax.DataAspectRatio=[1,1,1];

ax.XLim=[-30,5];

ax.YLim=[-5,40];

% 绘制图例

endPoint=[1,35];

for i=1:10

theta=T(i);

plot(endPoint(1)+[0,cos(theta).*2],endPoint(2)+[0,sin(theta).*2],'Color',[CM(i,:),.8],'LineWidth',3);

text(endPoint(1)+cos(theta).*2.7,endPoint(2)+sin(theta).*2.7,num2str(i-1),'Color',[1,1,1].*.7,...

'FontSize',12,'FontWeight','bold','FontName','Cambria','HorizontalAlignment','center')

end

text(-15,35,'Random walk of \pi digits','Color',[1,1,1],'FontName','Cambria',...

'HorizontalAlignment','center','FontSize',25,'FontAngle','italic')

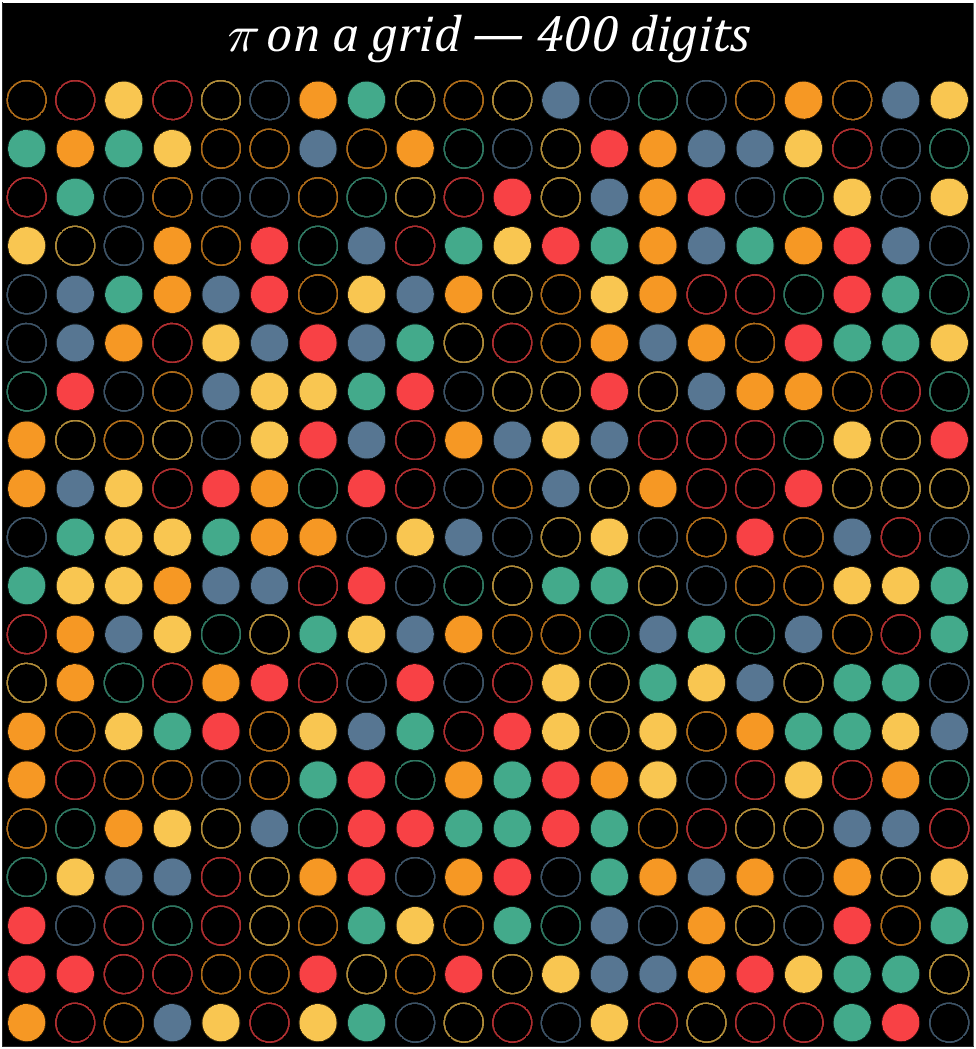

9 grid chart

Pi=[3,getPi(399)];

% 配色数据

CM=[248,65,69;246,152,36;249,198,81;67,170,139;87,118,146]./255;

% 绘制圆圈

hold on

t=linspace(0,2*pi,100);

x=cos(t).*.8.*.5;

y=sin(t).*.8.*.5;

for i=1:400

[col,row]=ind2sub([20,20],i);

if mod(Pi(i),2)==0

fill(x+col,y+row,CM(round((Pi(i)+1)/2),:),'LineWidth',1,'EdgeAlpha',.8)

else

fill(x+col,y+row,[0,0,0],'EdgeColor',CM(round((Pi(i)+1)/2),:),'LineWidth',1,'EdgeAlpha',.7)

end

end

text(10.5,-.4,'\pi on a grid — 400 digits','Color',[1,1,1],'FontName','Cambria',...

'HorizontalAlignment','center','FontSize',25,'FontAngle','italic')

% 图窗和坐标区域修饰

set(gcf,'Position',[200,100,820,820]);

ax=gca;

ax.YDir='reverse';

ax.XLim=[.5,20.5];

ax.YLim=[-1,20.5];

ax.XTick=[];

ax.YTick=[];

ax.Color=[0,0,0];

ax.DataAspectRatio=[1,1,1];

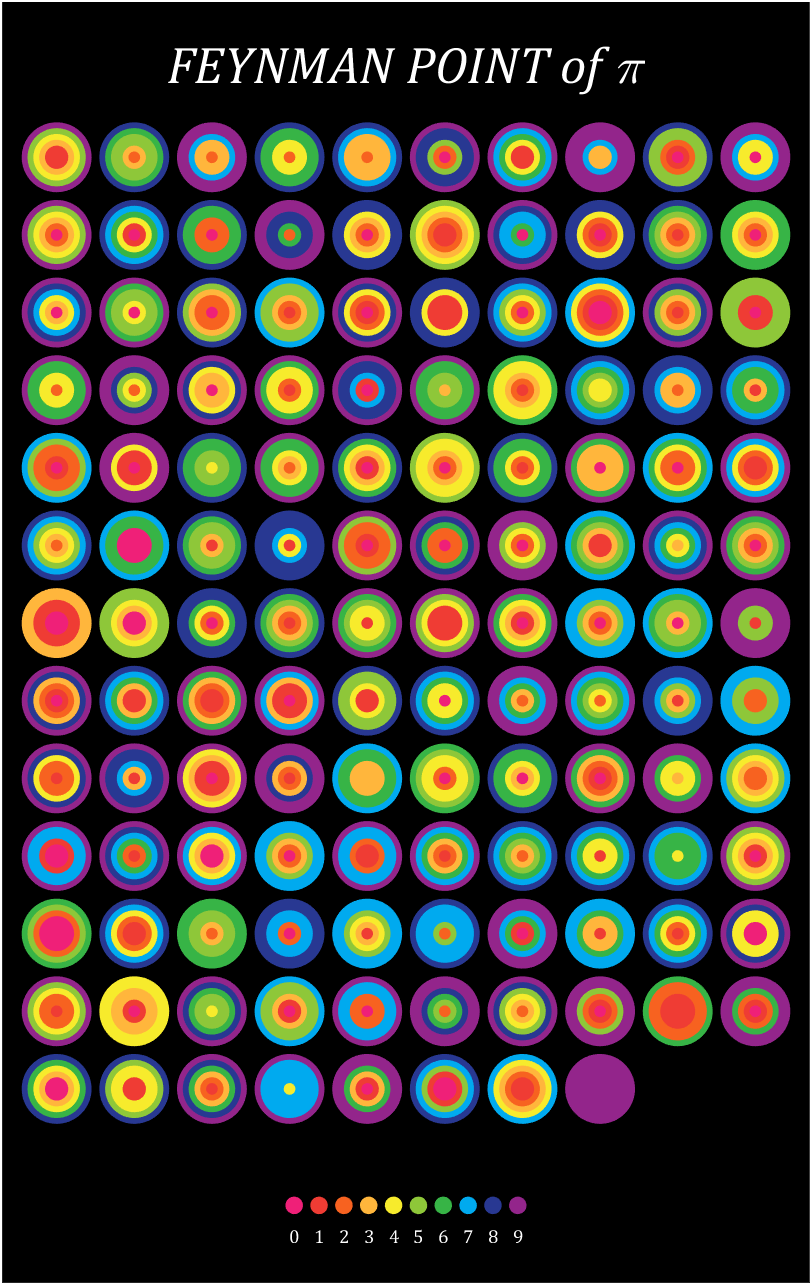

10 scale grid diagram

Let's still put the numbers in the form of circles, but the difference is that six numbers are grouped together, and the pure purple circle at the end is the six 9s that we are familiar with decimal places 762-767

Pi=[3,getPi(767)];

% 762-767

% 配色数据

CM=[239,32,120;239,60,52;247,98,32;255,182,60;247,235,44;

142,199,57;55,180,70;0,170,239;40,56,146;147,37,139]./255;

% 绘制圆圈

hold on

t=linspace(0,2*pi,100);

x=cos(t).*.9.*.5;

y=sin(t).*.9.*.5;

for i=1:6:length(Pi)

n=round((i-1)/6+1);

[col,row]=ind2sub([10,13],n);

tNum=Pi(i:i+5);

numNum=find([diff(sort(tNum)),1]);

numNum=[numNum(1),diff(numNum)];

cumNum=cumsum(numNum);

uniNum=unique(tNum);

for j=length(cumNum):-1:1

fill(x./6.*cumNum(j)+col,y./6.*cumNum(j)+row,CM(uniNum(j)+1,:),'EdgeColor','none')

end

end

% 绘制图例

for i=1:10

fill(x./4+5.5+(i-5.5)*.32,y./4+14.5,CM(i,:),'EdgeColor','none')

text(5.5+(i-5.5)*.32,14.9,num2str(i-1),'Color',[1,1,1],'FontSize',...

9,'FontName','Cambria','HorizontalAlignment','center')

end

text(5.5,-.2,'FEYNMAN POINT of \pi','Color',[1,1,1],'FontName','Cambria',...

'HorizontalAlignment','center','FontSize',25,'FontAngle','italic')

% 图窗和坐标区域修饰

set(gcf,'Position',[200,100,600,820]);

ax=gca;

ax.YDir='reverse';

ax.Position=[0,0,1,1];

ax.XLim=[.3,10.7];

ax.YLim=[-1,15.5];

ax.XTick=[];

ax.YTick=[];

ax.Color=[0,0,0];

ax.DataAspectRatio=[1,1,1];

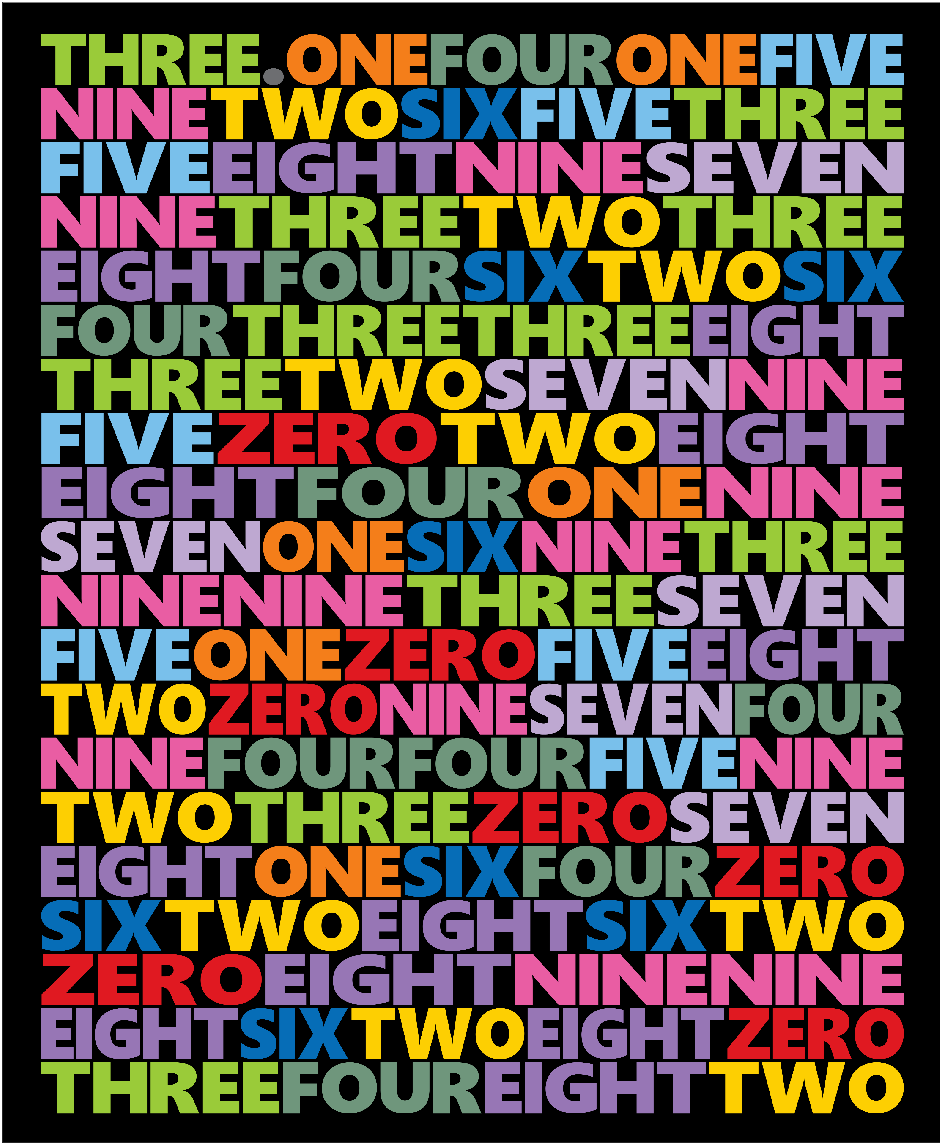

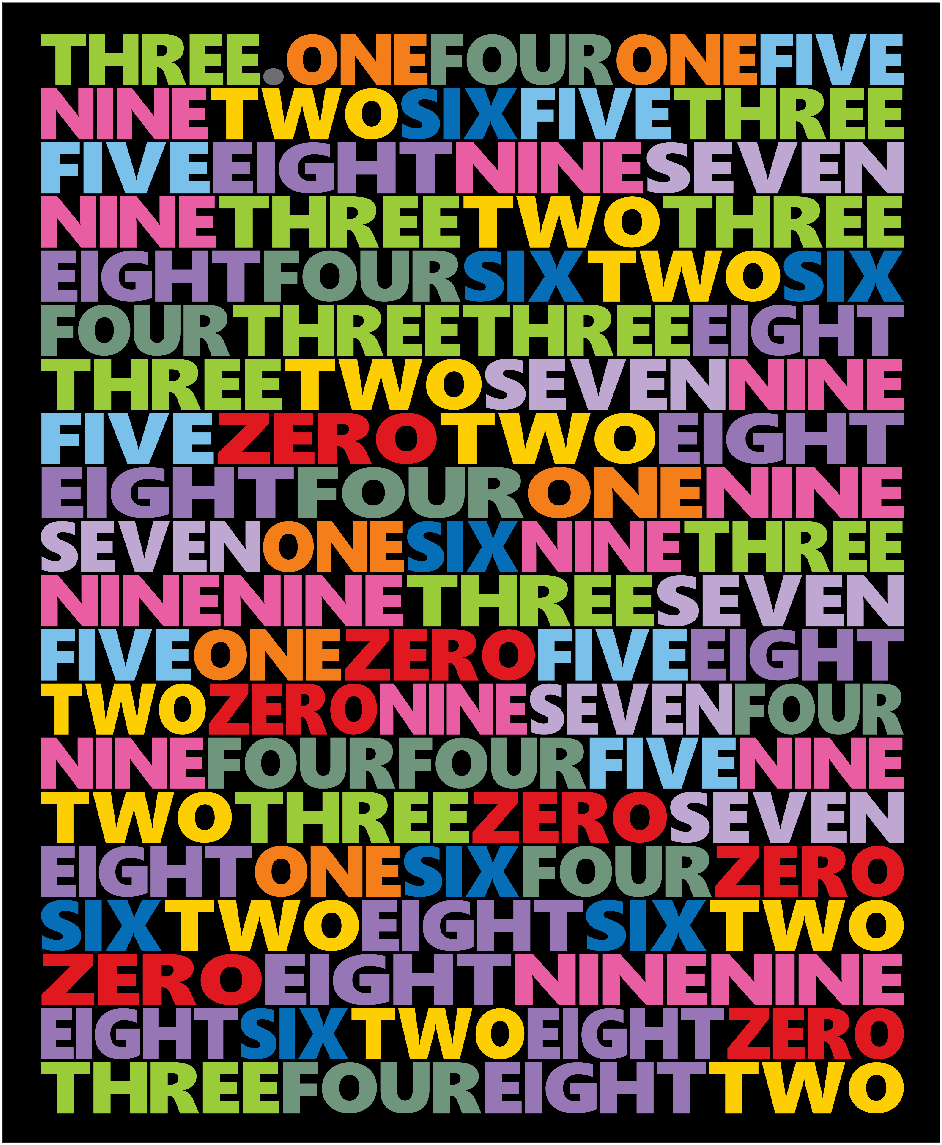

11 text chart

First, write a code to generate an image of each letter:

function getLogo

if ~exist('image','dir')

mkdir('image\')

end

logoSet=['.',char(65:90)];

for i=1:27

figure();

ax=gca;

ax.XLim=[-1,1];

ax.YLim=[-1,1];

ax.XColor='none';

ax.YColor='none';

ax.DataAspectRatio=[1,1,1];

logo=logoSet(i);

hold on

text(0,0,logo,'HorizontalAlignment','center','FontSize',320,'FontName','Segoe UI Black')

exportgraphics(ax,['image\',logo,'.png'])

close

end

dotPic=imread('image\..png');

newDotPic=uint8(ones([400,size(dotPic,2),3]).*255);

newDotPic(end-size(dotPic,1)+1:end,:,1)=dotPic(:,:,1);

newDotPic(end-size(dotPic,1)+1:end,:,2)=dotPic(:,:,2);

newDotPic(end-size(dotPic,1)+1:end,:,3)=dotPic(:,:,3);

imwrite(newDotPic,'image\..png')

S=20;

for i=1:27

logo=logoSet(i);

tPic=imread(['image\',logo,'.png']);

sz=size(tPic,[1,2]);

sz=round(sz./sz(1).*400);

tPic=imresize(tPic,sz);

tBox=uint8(255.*ones(size(tPic,[1,2])+S));

tBox(S+1:S+size(tPic,1),S+1:S+size(tPic,2))=tPic(:,:,1);

imwrite(cat(3,tBox,tBox,tBox),['image\',logo,'.png'])

end

end

Pi=[3,-1,getPi(150)];

CM=[109,110,113;224,25,33;244,126,26;253,207,2;154,203,57;111,150,124;

121,192,235;6,109,183;190,168,209;151,118,181;233,93,163]./255;

ST={'.','ZERO','ONE','TWO','THREE','FOUR','FIVE','SIX','SEVEN','EIGHT','NINE'};

n=1;

hold on

% 循环绘制字母

for i=1:20%:10

STList='';

NMList=[];

PicListR=uint8(zeros(400,0));

PicListG=uint8(zeros(400,0));

PicListB=uint8(zeros(400,0));

% PicListA=uint8(zeros(400,0));

for j=1:6

STList=[STList,ST{Pi(n)+2}];

NMList=[NMList,ones(size(ST{Pi(n)+2})).*(Pi(n)+2)];

n=n+1;

if length(STList)>15&&length(STList)+length(ST{Pi(n)+2})>20

break;

end

end

for k=1:length(STList)

tPic=imread(['image\',STList(k),'.png']);

% PicListA=[PicListA,tPic(:,:,1)];

PicListR=[PicListR,(255-tPic(:,:,1)).*CM(NMList(k),1)];

PicListG=[PicListG,(255-tPic(:,:,2)).*CM(NMList(k),2)];

PicListB=[PicListB,(255-tPic(:,:,3)).*CM(NMList(k),3)];

end

PicList=cat(3,PicListR,PicListG,PicListB);

image([-1200,1200],[0,150]-(i-1)*150,flipud(PicList))

end

% 图窗及坐标区域修饰

set(gcf,'Position',[200,100,600,820]);

ax=gca;

ax.DataAspectRatio=[1,1,1];

ax.XLim=[-1300,1300];

ax.Position=[0,0,1,1];

ax.XTick=[];

ax.YTick=[];

ax.Color=[0,0,0];

ax.YLim=[-19*150-80,230];

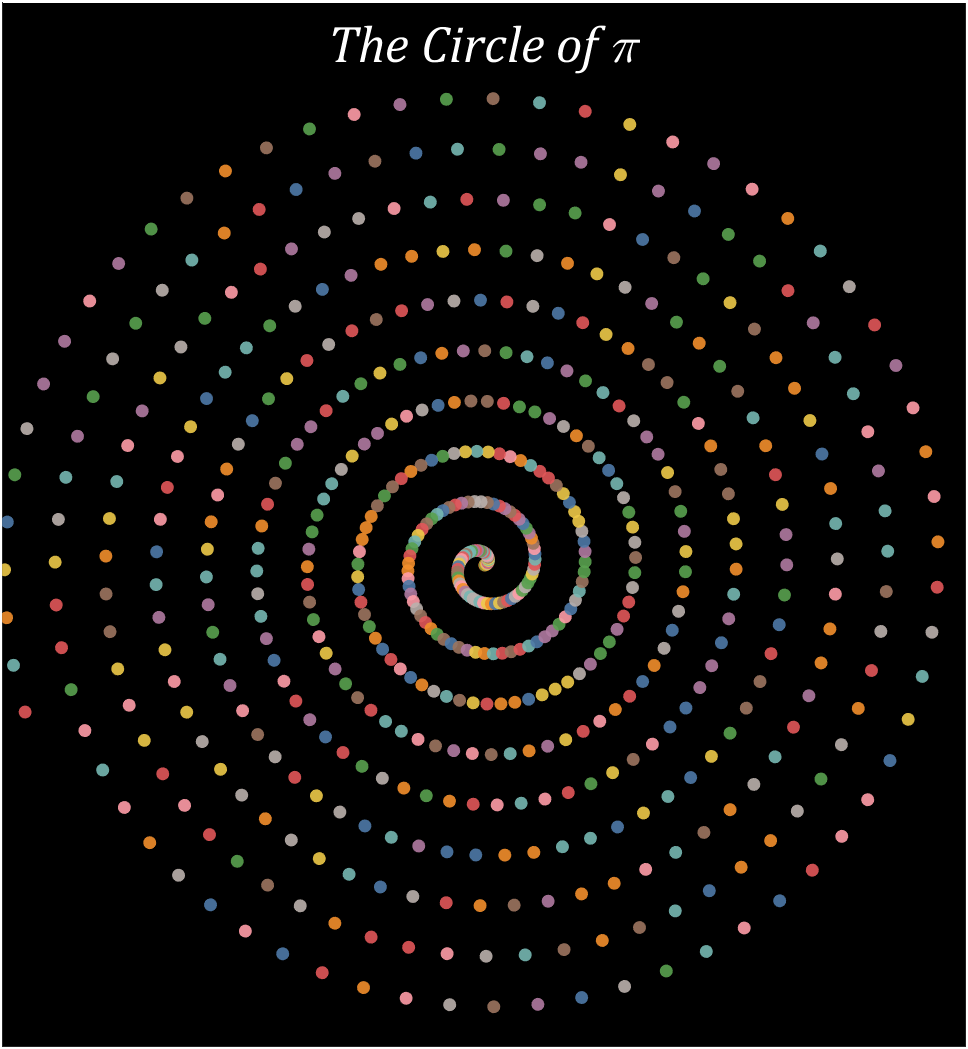

12 spiral chart

Pi=getPi(600);

% 配色列表

CM=[78,121,167;242,142,43;225,87,89;118,183,178;89,161,79;

237,201,72;176,122,161;255,157,167;156,117,95;186,176,172]./255;

% 绘制圆圈

hold on

t=linspace(0,2*pi,100);

x=cos(t).*.8;

y=sin(t).*.8;

for i=1:600

X=i.*cos(i./10)./10;

Y=i.*sin(i./10)./10;

fill(X+x,Y+y,CM(Pi(i)+1,:),'EdgeColor','none','FaceAlpha',.9)

end

text(0,65,'The Circle of \pi','Color',[1,1,1],'FontName','Cambria',...

'HorizontalAlignment','center','FontSize',25,'FontAngle','italic')

% 图窗和坐标区域修饰

set(gcf,'Position',[200,100,820,820]);

ax=gca;

ax.XLim=[-60,60];

ax.YLim=[-60,70];

ax.XTick=[];

ax.YTick=[];

ax.Color=[0,0,0];

ax.DataAspectRatio=[1,1,1];

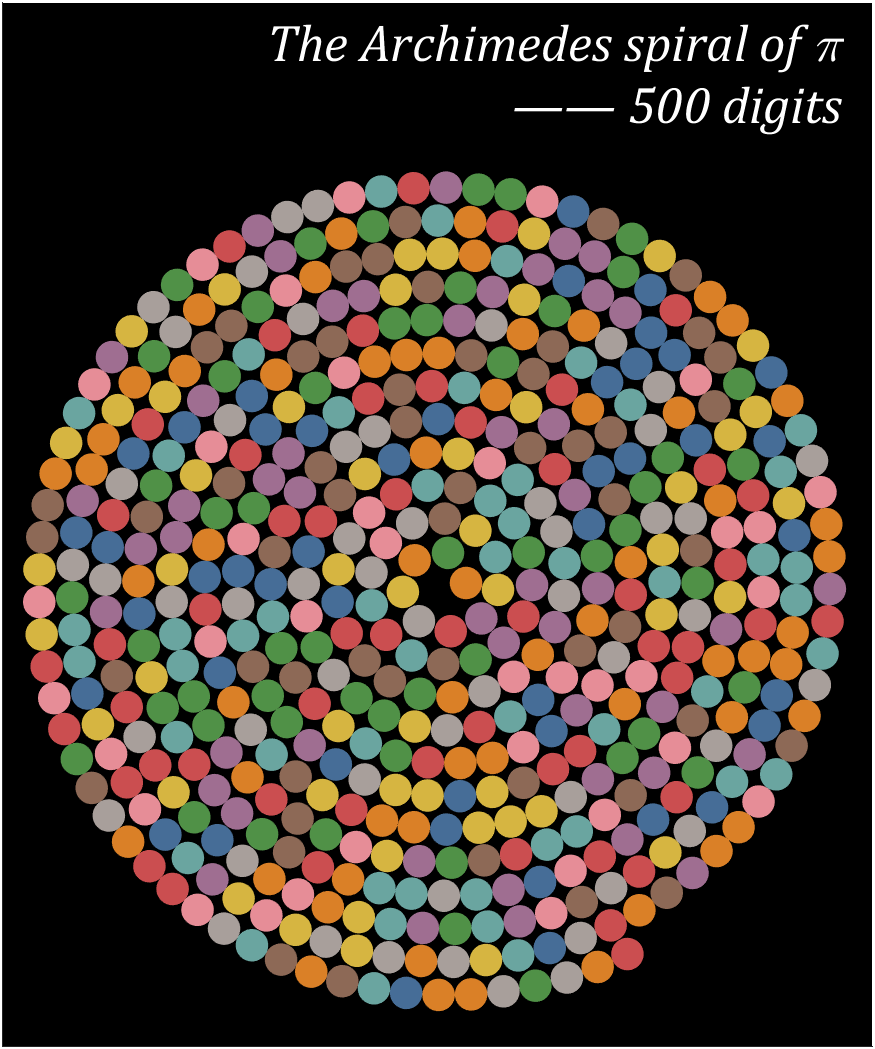

13 Archimedean spiral diagram

a=1;b=.227;

Pi=getPi(500);

% 配色列表

CM=[78,121,167;242,142,43;225,87,89;118,183,178;89,161,79;

237,201,72;176,122,161;255,157,167;156,117,95;186,176,172]./255;

% 绘制圆圈

hold on

T=0;R=1;

t=linspace(0,2*pi,100);

x=cos(t).*.7;

y=sin(t).*.7;

for i=1:500

X=R.*cos(T);Y=R.*sin(T);

fill(X+x,Y+y,CM(Pi(i)+1,:),'EdgeColor','none','FaceAlpha',.9)

T=T+1./R.*1.4;

R=a+b*T;

end

text(17.25,22,{'The Archimedes spiral of \pi';'—— 500 digits'},...

'Color',[1,1,1],'FontName','Cambria',...

'HorizontalAlignment','right','FontSize',25,'FontAngle','italic')

% 图窗和坐标区域修饰

set(gcf,'Position',[200,100,820,820]);

ax=gca;

ax.XLim=[-19,18.5];

ax.YLim=[-20,25];

ax.XTick=[];

ax.YTick=[];

ax.Color=[0,0,0];

ax.DataAspectRatio=[1,1,1];

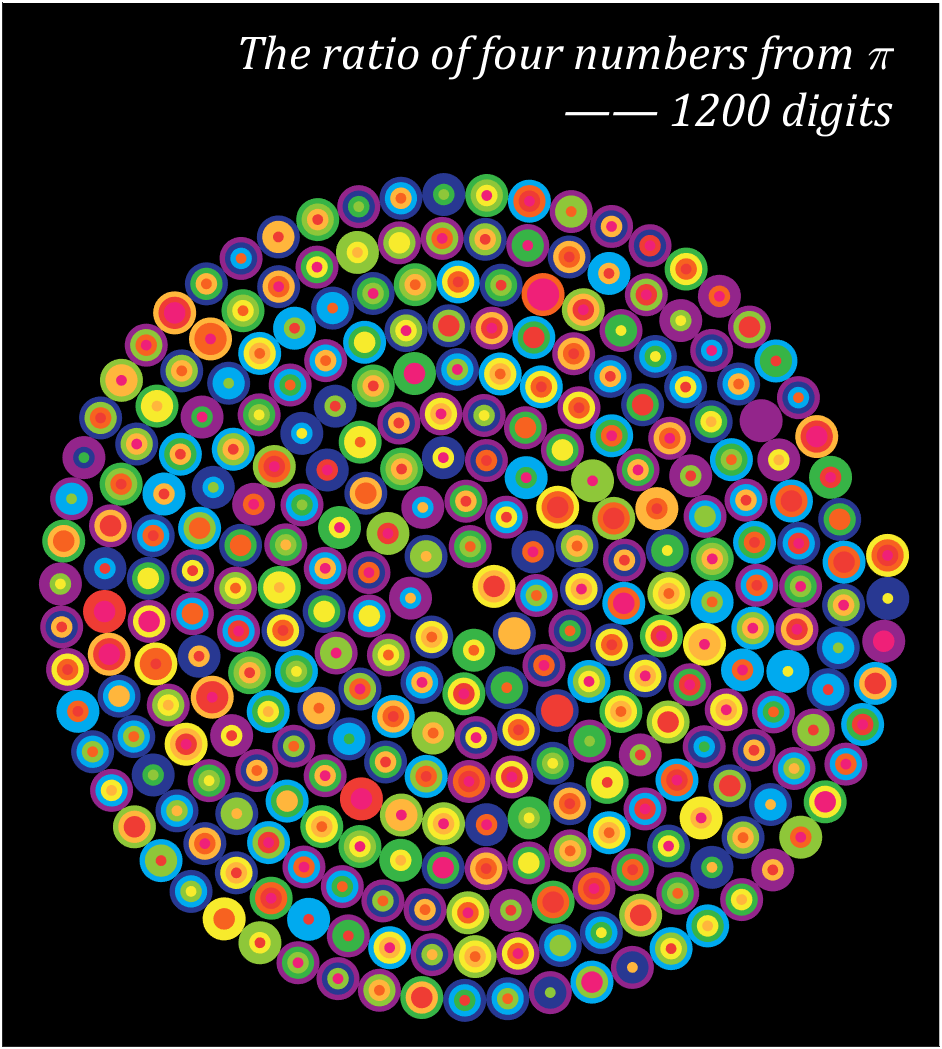

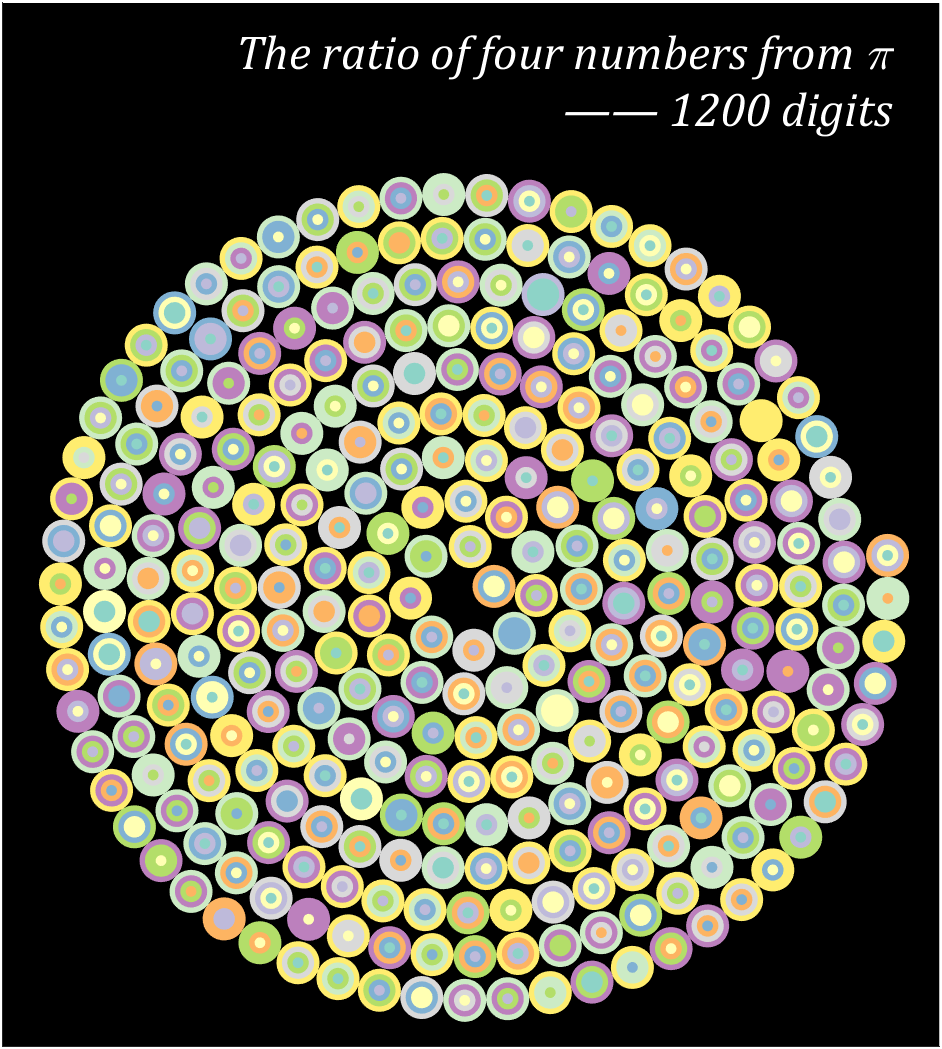

14 proportional Archimedean spiral diagram

Pi=[3,getPi(1199)];

% 配色数据

CM=[239,32,120;239,60,52;247,98,32;255,182,60;247,235,44;

142,199,57;55,180,70;0,170,239;40,56,146;147,37,139]./255;

% CM=slanCM(184,10);

% 绘制圆圈

hold on

T=0;R=1;

t=linspace(0,2*pi,100);

x=cos(t).*.7;

y=sin(t).*.7;

for i=1:4:length(Pi)

X=R.*cos(T);Y=R.*sin(T);

tNum=Pi(i:i+3);

numNum=find([diff(sort(tNum)),1]);

numNum=[numNum(1),diff(numNum)];

cumNum=cumsum(numNum);

uniNum=unique(tNum);

for j=length(cumNum):-1:1

fill(x./4.*cumNum(j)+X,y./4.*cumNum(j)+Y,CM(uniNum(j)+1,:),'EdgeColor','none')

end

T=T+1./R.*1.4;

R=a+b*T;

end

text(14,16.5,{'The ratio of four numbers from \pi';'—— 1200 digits'},...

'Color',[1,1,1],'FontName','Cambria',...

'HorizontalAlignment','right','FontSize',23,'FontAngle','italic')

% 图窗和坐标区域修饰

set(gcf,'Position',[200,100,820,820]);

ax=gca;

ax.XLim=[-15,15.5];

ax.YLim=[-15,19];

ax.XTick=[];

ax.YTick=[];

ax.Color=[0,0,0];

ax.DataAspectRatio=[1,1,1];

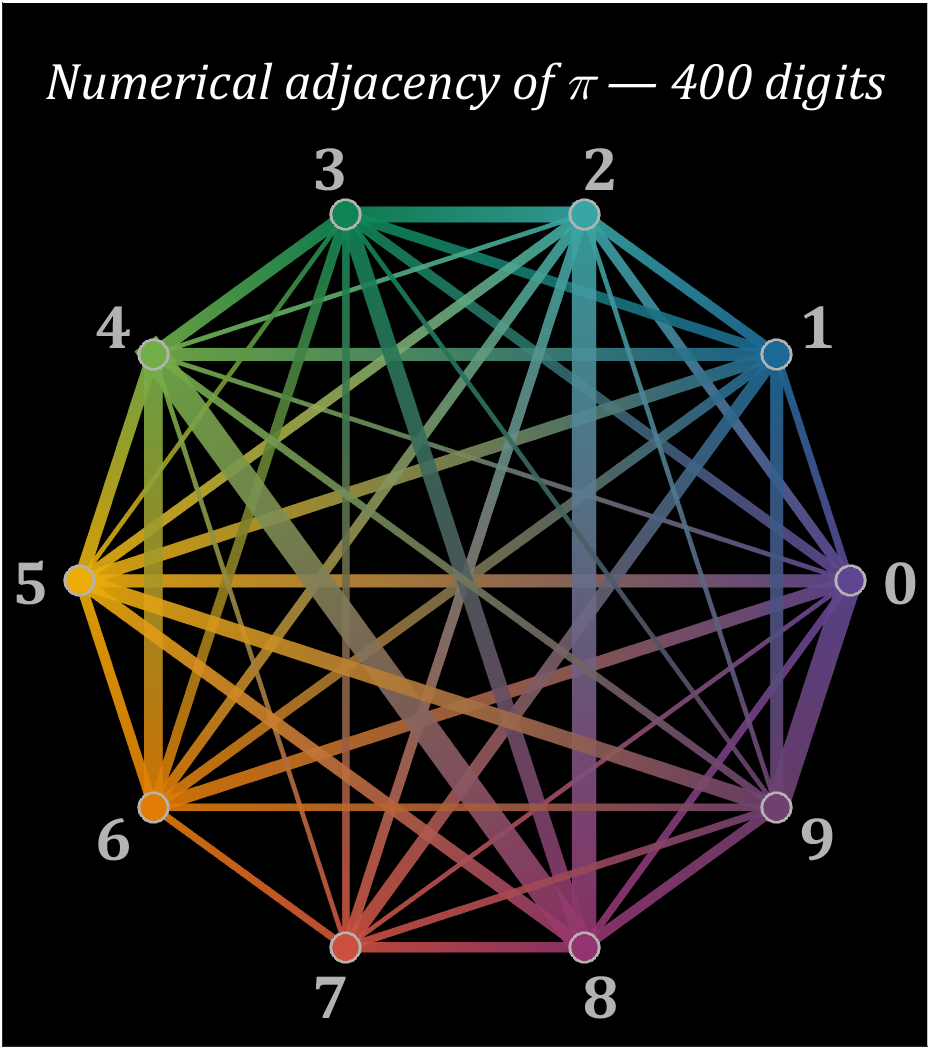

15 graph

% 构建连接矩阵

corrMat=zeros(10,10);

Pi=getPi(401);

for i=1:400

corrMat(Pi(i)+1,Pi(i+1)+1)=corrMat(Pi(i)+1,Pi(i+1)+1)+1;

end

% 配色列表

colorList=[0.3725 0.2745 0.5647

0.1137 0.4118 0.5882

0.2196 0.6510 0.6471

0.0588 0.5216 0.3294

0.4510 0.6863 0.2824

0.9294 0.6784 0.0314

0.8824 0.4863 0.0196

0.8000 0.3137 0.2431

0.5804 0.2039 0.4314

0.4353 0.2510 0.4392];

t=linspace(0,2*pi,11);t=t(1:10)';

posXY=[cos(t),sin(t)];

maxWidth=max(corrMat(corrMat>0));

minWidth=min(corrMat(corrMat>0));

ttList=linspace(0,1,3)';

% 循环绘图

hold on

for i=1:size(corrMat,1)

for j=i+1:size(corrMat,2)

if corrMat(i,j)>0

tW=(corrMat(i,j)-minWidth)./(maxWidth-minWidth);

colorData=(1-ttList).*colorList(i,:)+ttList.*colorList(j,:);

CData(:,:,1)=colorData(:,1);

CData(:,:,2)=colorData(:,2);

CData(:,:,3)=colorData(:,3);

% 绘制连线

fill(linspace(posXY(i,1),posXY(j,1),3),...

linspace(posXY(i,2),posXY(j,2),3),[0,0,0],'LineWidth',tW.*12+1,...

'CData',CData,'EdgeColor','interp','EdgeAlpha',.7,'FaceAlpha',.7)

end

end

% 绘制圆点

scatter(posXY(i,1),posXY(i,2),200,'filled','LineWidth',1.2,...

'MarkerFaceColor',colorList(i,:),'MarkerEdgeColor',[.7,.7,.7]);

text(posXY(i,1).*1.13,posXY(i,2).*1.13,num2str(i-1),'Color',[1,1,1].*.7,...

'FontSize',30,'FontWeight','bold','FontName','Cambria','HorizontalAlignment','center')

end

text(0,1.3,'Numerical adjacency of \pi — 400 digits','Color',[1,1,1],'FontName','Cambria',...

'HorizontalAlignment','center','FontSize',25,'FontAngle','italic')

% 图窗和坐标区域修饰

set(gcf,'Position',[200,100,820,820]);

ax=gca;

ax.XLim=[-1.2,1.2];

ax.YLim=[-1.21,1.5];

ax.XTick=[];

ax.YTick=[];

ax.Color=[0,0,0];

ax.DataAspectRatio=[1,1,1];

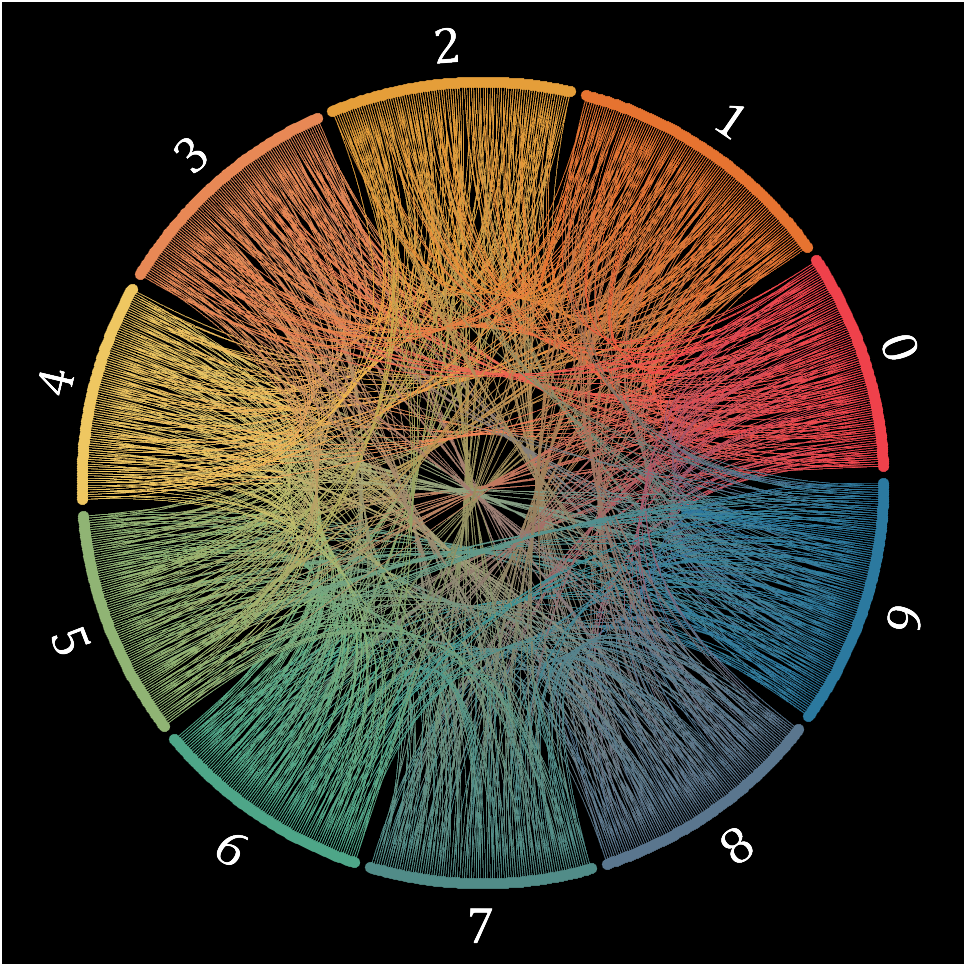

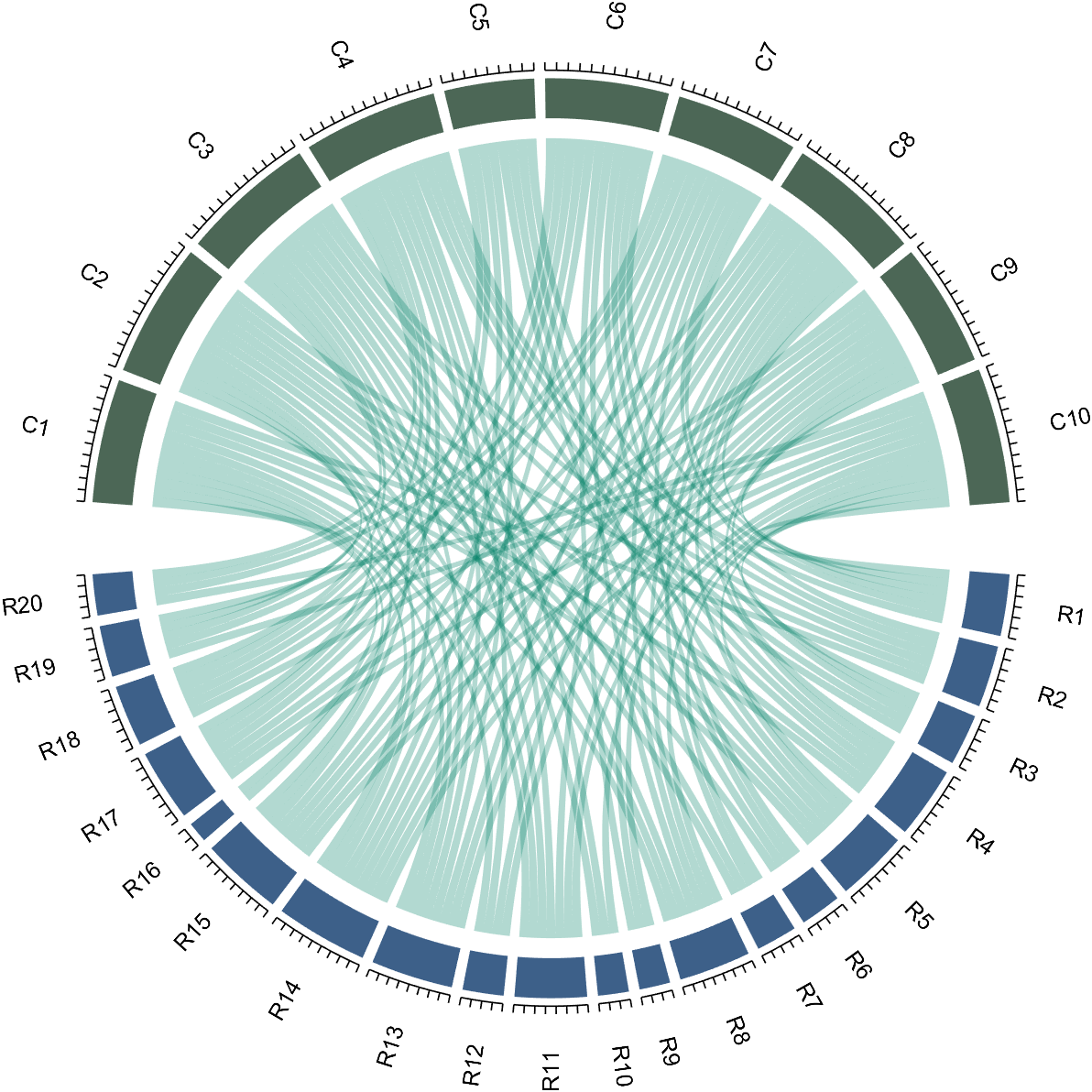

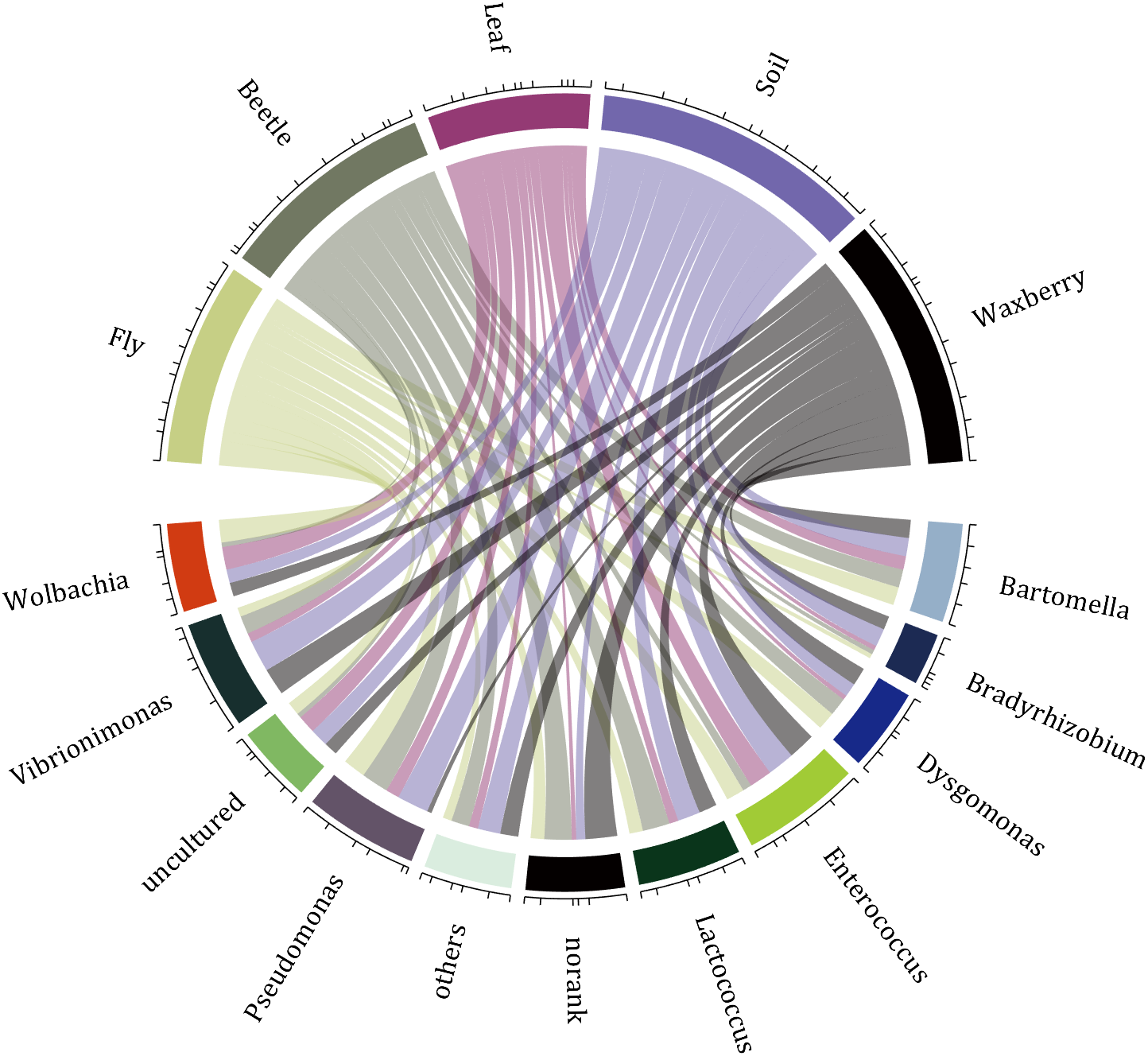

16 circos chart

Need to use this tool:

Class=getPi(1001)+1;

Data=diag(ones(1,1000),-1);

className={'0','1','2','3','4','5','6','7','8','9'};

colorOrder=[239,65,75;230,115,48;229,158,57;232,136,85;239,199,97;

144,180,116;78,166,136;81,140,136;90,118,142;43,121,159]./255;

CC=circosChart(Data,Class,'ClassName',className,'ColorOrder',colorOrder);

CC=CC.draw();

ax=gca;

ax.Color=[0,0,0];

CC.setClassLabel('Color',[1,1,1],'FontSize',25,'FontName','Cambria')

CC.setLine('LineWidth',.7)

YOU CAN GET ALL CODE HERE:

Happy Pi Day

Happy Pi Day

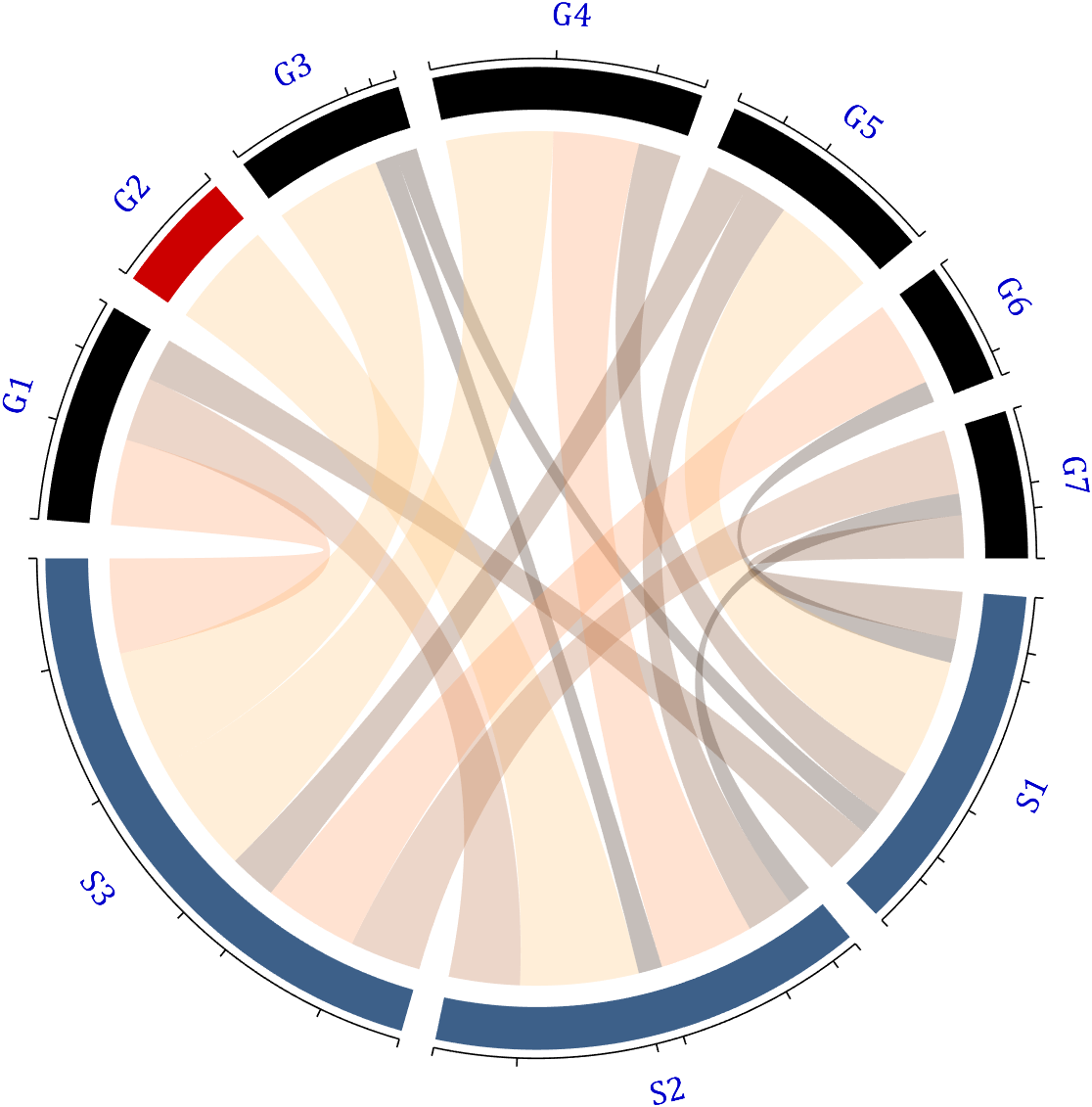

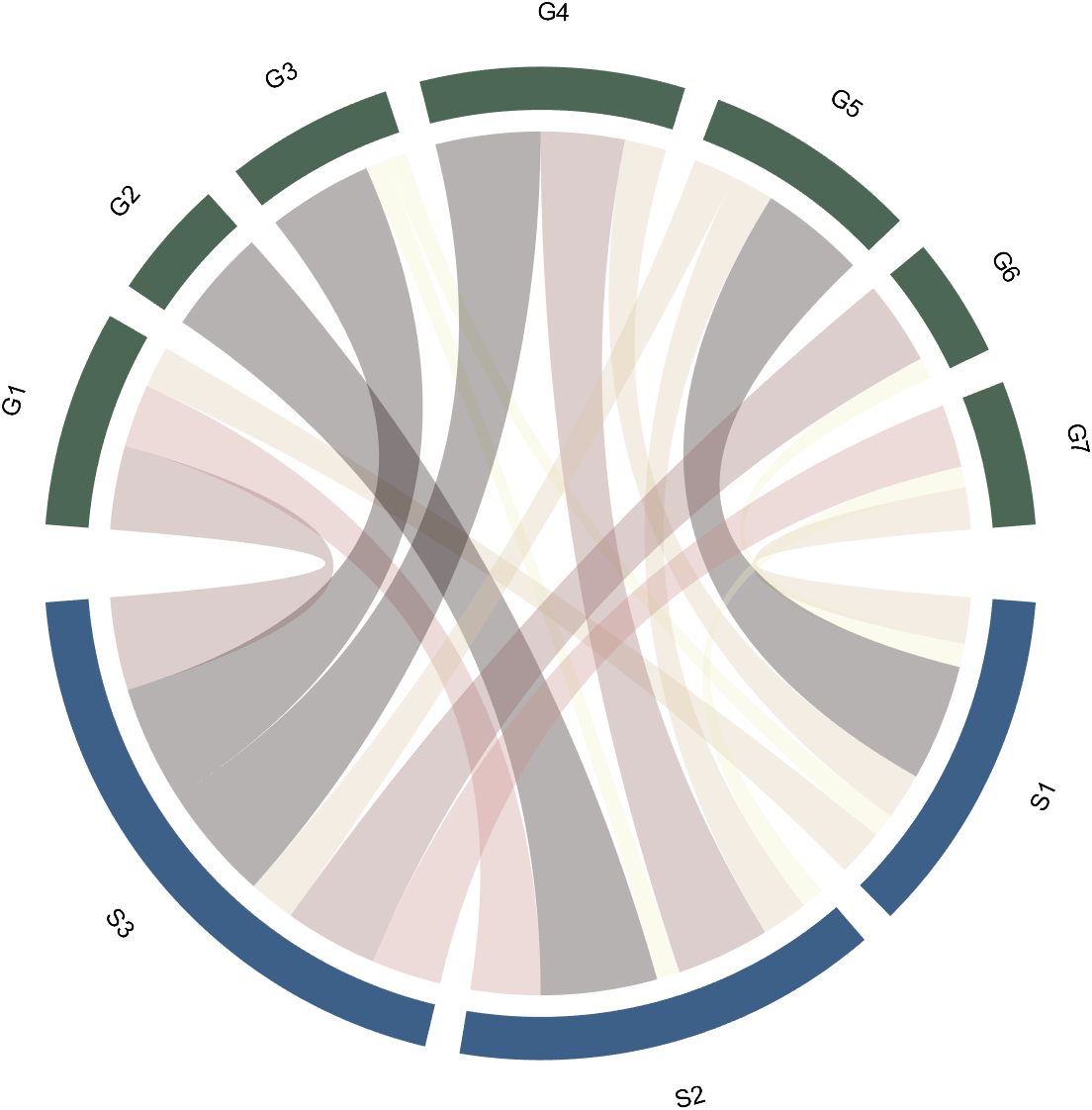

Chord diagrams are very common in Python and R, but there are no related functions in MATLAB before. It is not easy to draw chord diagrams of the same quality as R language, But I created a MATLAB tool that could almost do it.

↓ ↓ ↓ ↓ ↓ ↓ ↓ ↓ ↓ ↓

↑ ↑ ↑ ↑ ↑ ↑ ↑ ↑ ↑ ↑

Here is the help document:

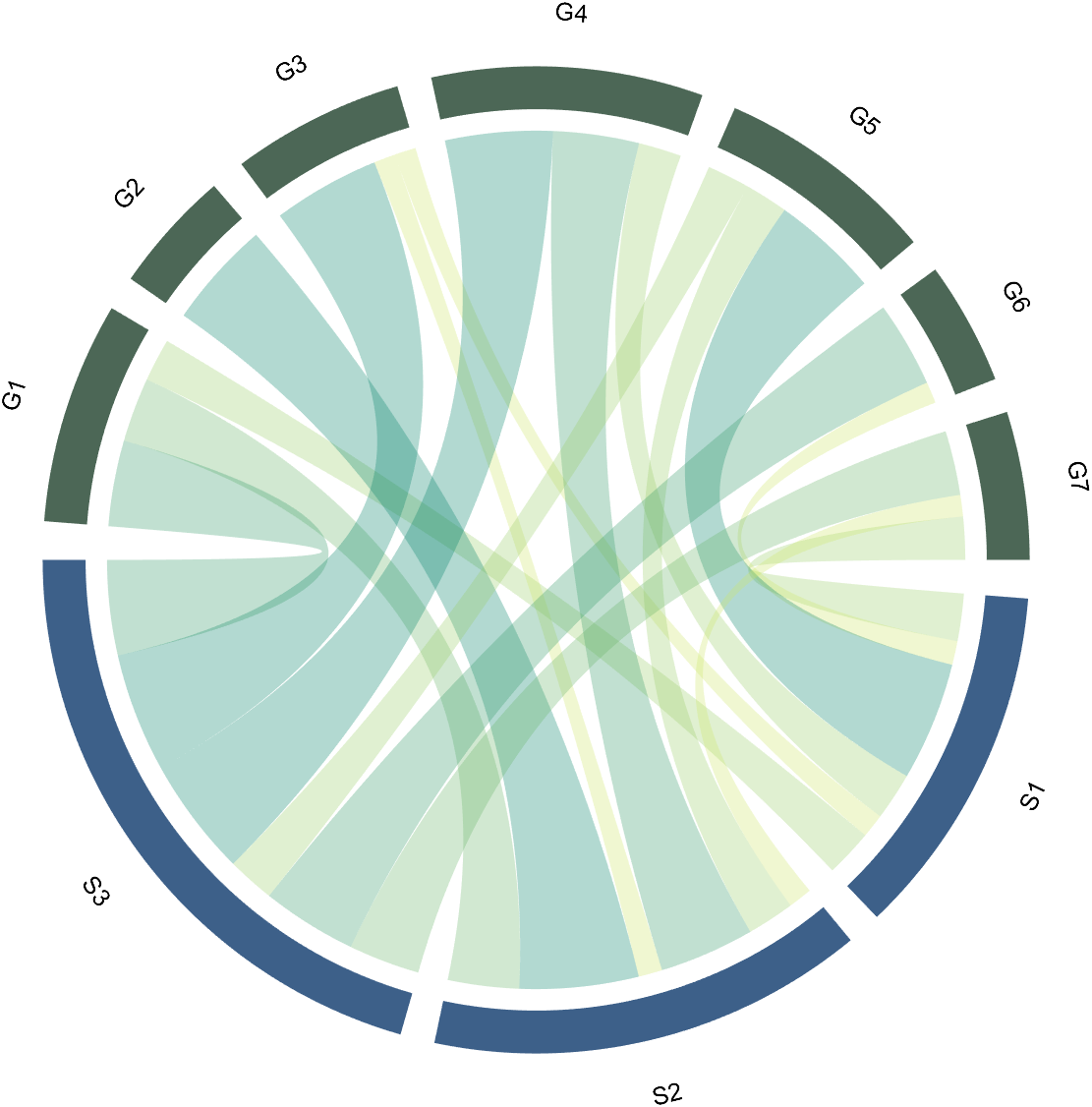

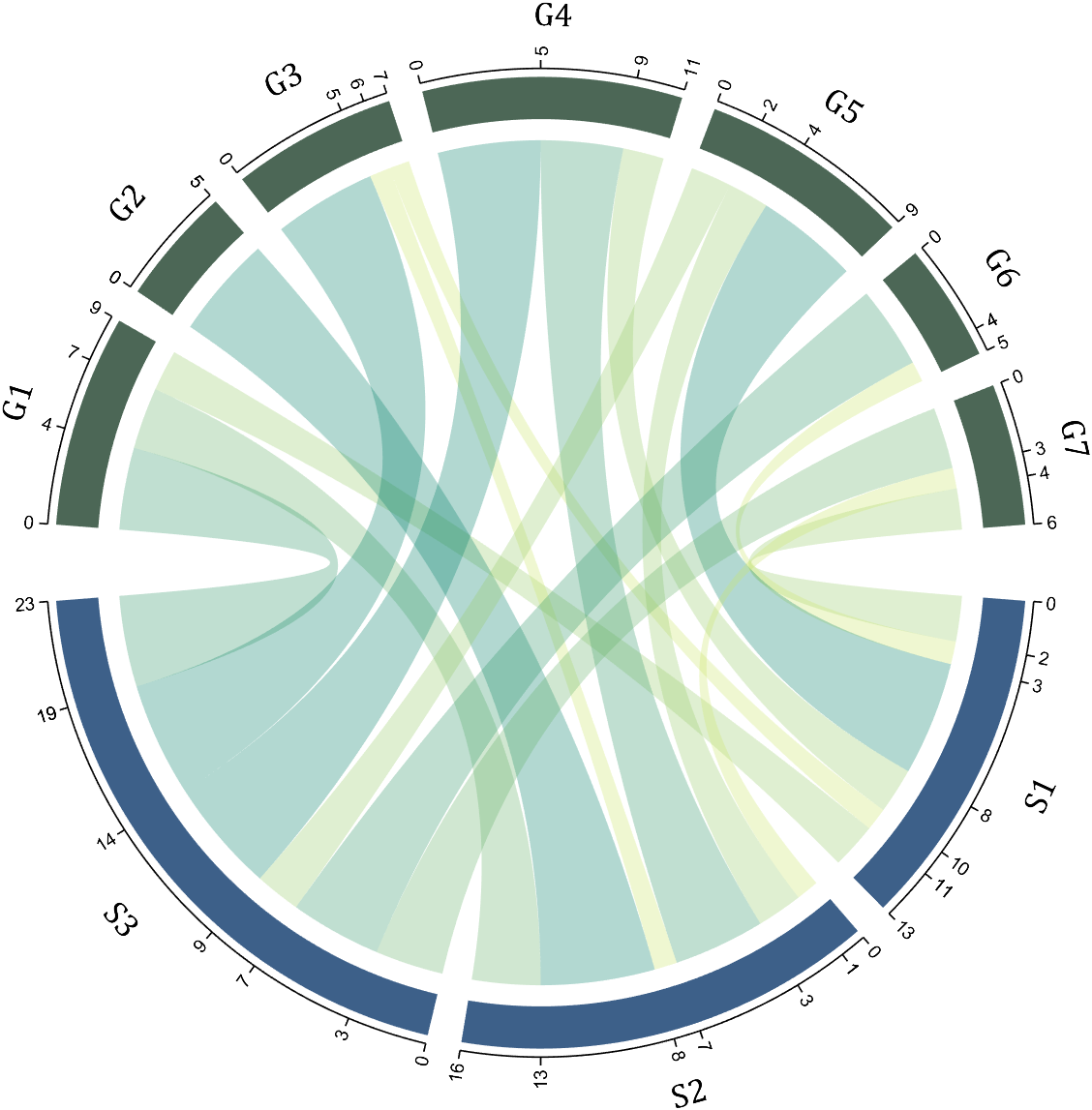

1 Data Format

The data requirement is a numerical matrix with all values greater than or equal to 0, or a table array, or a numerical matrix and cell array for names. First, give an example of a numerical matrix:

1.1 Numerical Matrix

dataMat=randi([0,5],[5,4]);

% 绘图(draw)

CC=chordChart(dataMat);

CC=CC.draw();

Since each object is not named, it will be automatically named Rn and Cn

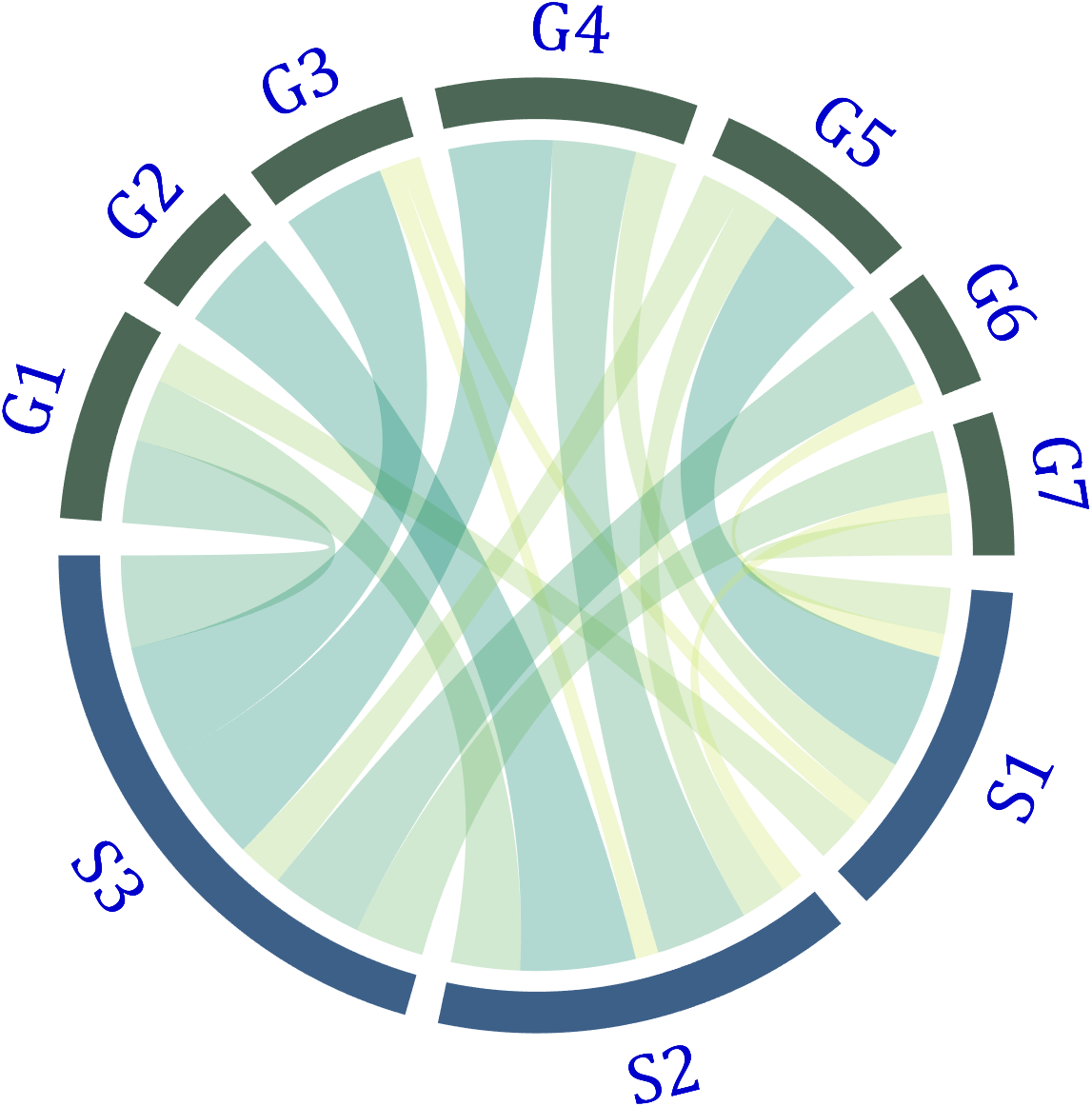

1.2 Numerical Matrix and Cell Array for Names

dataMat=[2 0 1 2 5 1 2;

3 5 1 4 2 0 1;

4 0 5 5 2 4 3];

colName={'G1','G2','G3','G4','G5','G6','G7'};

rowName={'S1','S2','S3'};

CC=chordChart(dataMat,'rowName',rowName,'colName',colName);

CC=CC.draw();

RowName should be the same size as the rows of the matrix

ColName should be the same size as the columns of the matrix

For this example, if the value in the second row and third column is 1, it indicates that there is an energy flow from S2 to G3, and a chord with a width of 1 is needed between these two.

1.3 Table Array

A table array in the following format is required:

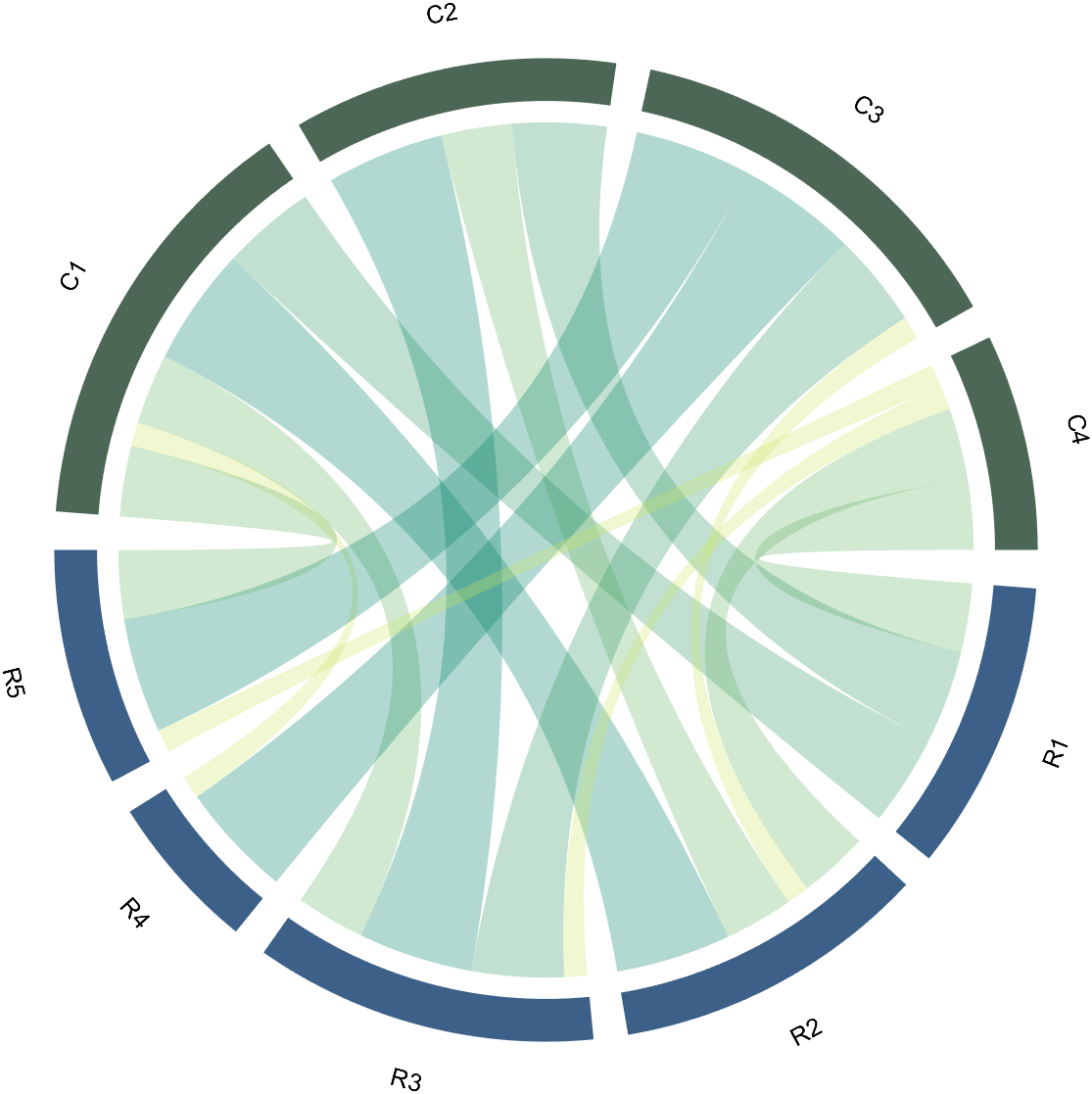

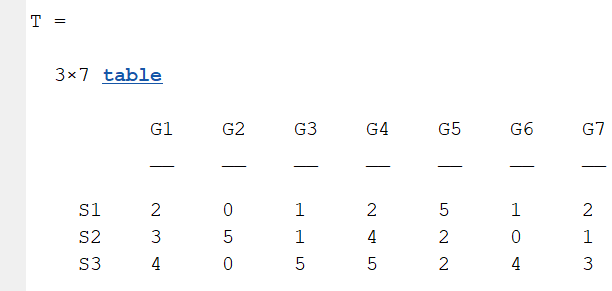

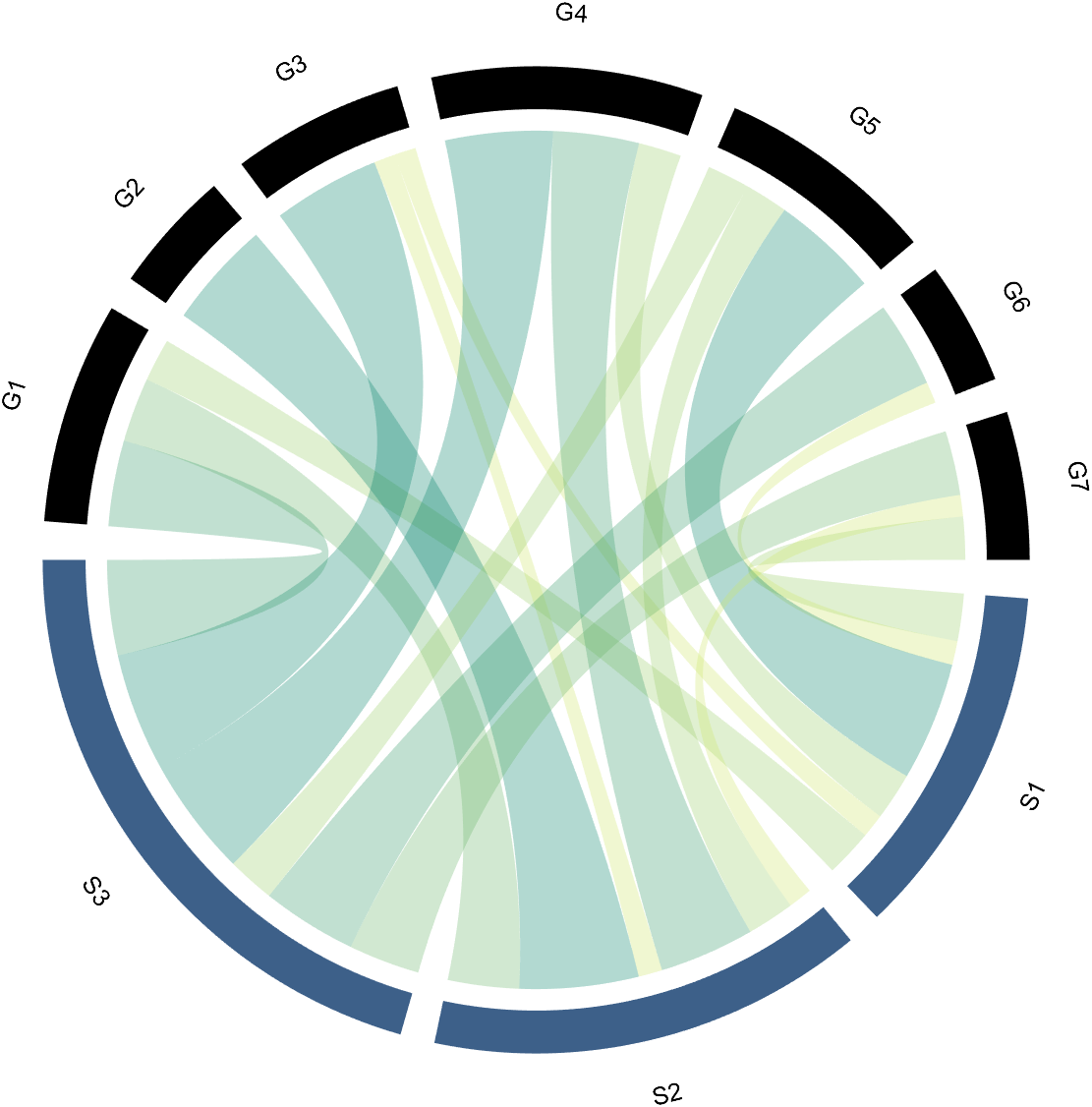

2 Decorate Chord

2.1 Batch modification of chords

Batch modification of chords can be done using the setChordProp function, and all properties of the Patch object can be modified. For example, modifying the color of the string, edge color, edge line sstyle, etc.:

CC.setChordProp('EdgeColor',[.3,.3,.3],'LineStyle','--',...

'LineWidth',.1,'FaceColor',[.3,.3,.3])

2.2 Individual Modification of Chord

The individual modification of chord can be done using the setChordMN function, where the values of m and n correspond exactly to the rows and columns of the original numerical matrix. For example, changing the color of the strings flowing from S2 to G4 to red:

CC.setChordMN(2,4,'FaceColor',[1,0,0])

2.3 Color Mapping of Chords

Just use function colormap to do so:

% version 1.7.0更新

% 可使用colormap函数直接修改颜色

% Colors can be adjusted directly using the function colormap(demo4)

colormap(flipud(pink))

3 Arc Shaped Block Decoration

3.1 Batch Decoration of Arc-Shaped Blocks

use:

- setSquareT_Prop

- setSquareF_Prop

to modify the upper and lower blocks separately, and all attributes of the Patch object can be modified. For example, batch modify the upper blocks (change to black):

CC.setSquareT_Prop('FaceColor',[0,0,0])

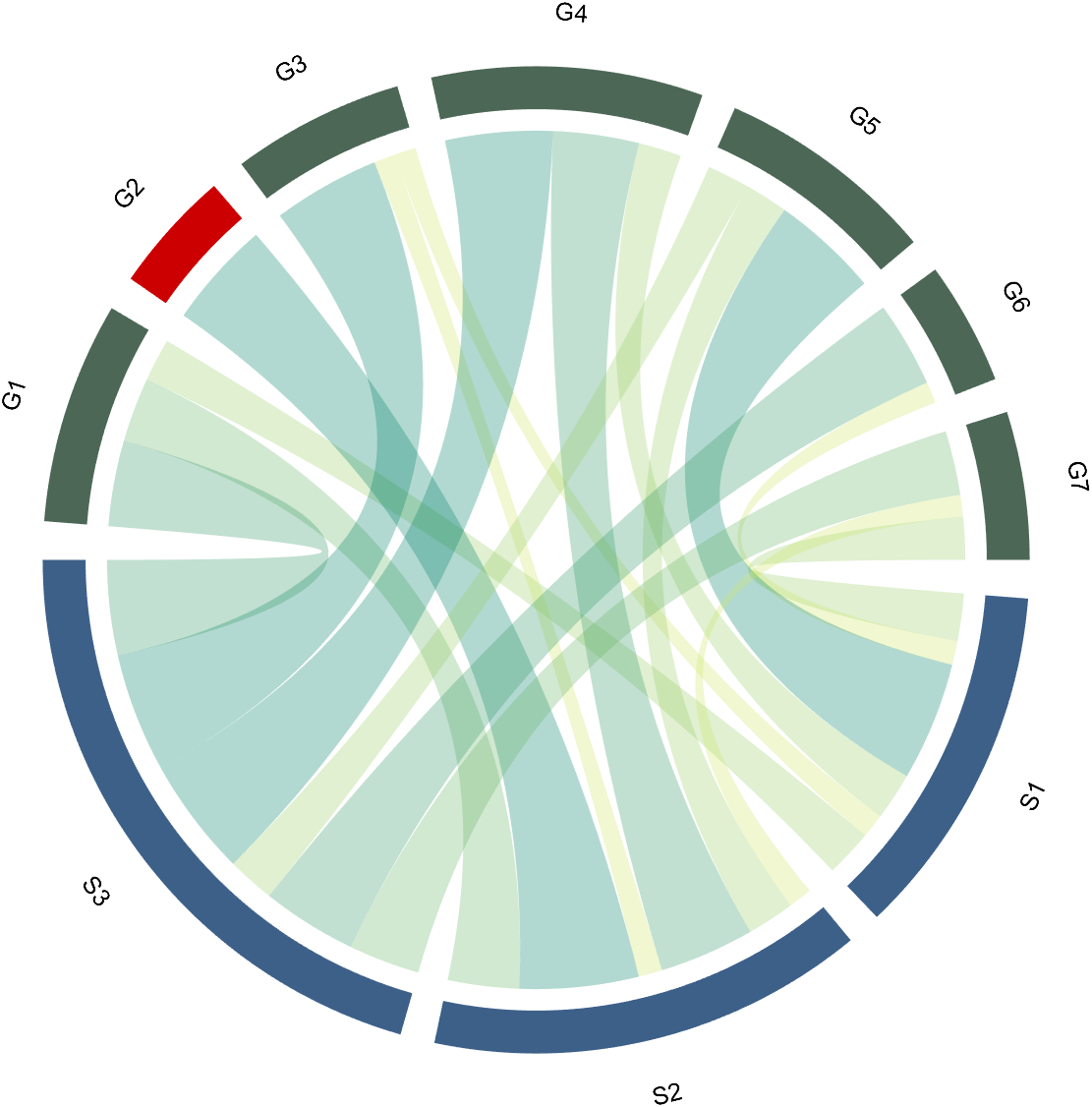

3.2 Arc-Shaped Blocks Individually Decoration

use:

- setSquareT_N

- setSquareF_N

to modify the upper and lower blocks separately. For example, modify the second block above separately (changed to red):

CC.setSquareT_N(2,'FaceColor',[.8,0,0])

4 Font Adjustment

Use the setFont function to adjust the font, and all properties of the text object can be modified. For example, changing the font size, font, and color of the text:

CC.setFont('FontSize',25,'FontName','Cambria','Color',[0,0,.8])

5 Show and Hide Ticks

Usage:

CC.tickState('on')

% CC.tickState('off')

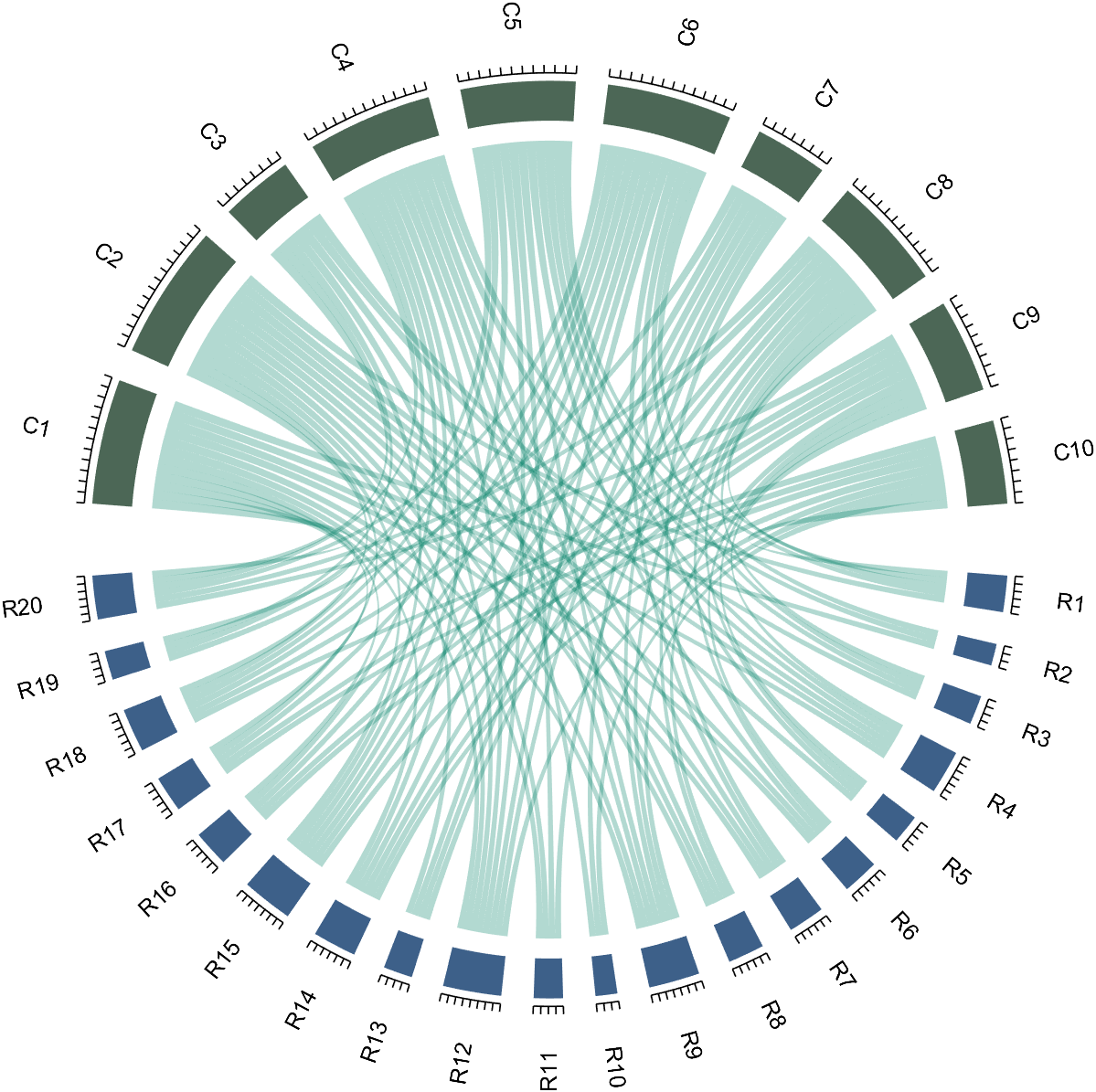

6 Attribute 'Sep' with Adjustable Square Spacing

If the matrix size is large, the drawing will be out of scale:

dataMat=randi([0,1],[20,10]);

CC=chordChart(dataMat);

CC=CC.draw();

% CC.tickState('on')

We can modify its Sep attribute:

dataMat=randi([0,1],[20,10]);

% use Sep to decrease space (separation)

% 使用 sep 减小空隙

CC=chordChart(dataMat,'Sep',1/120);

CC=CC.draw();

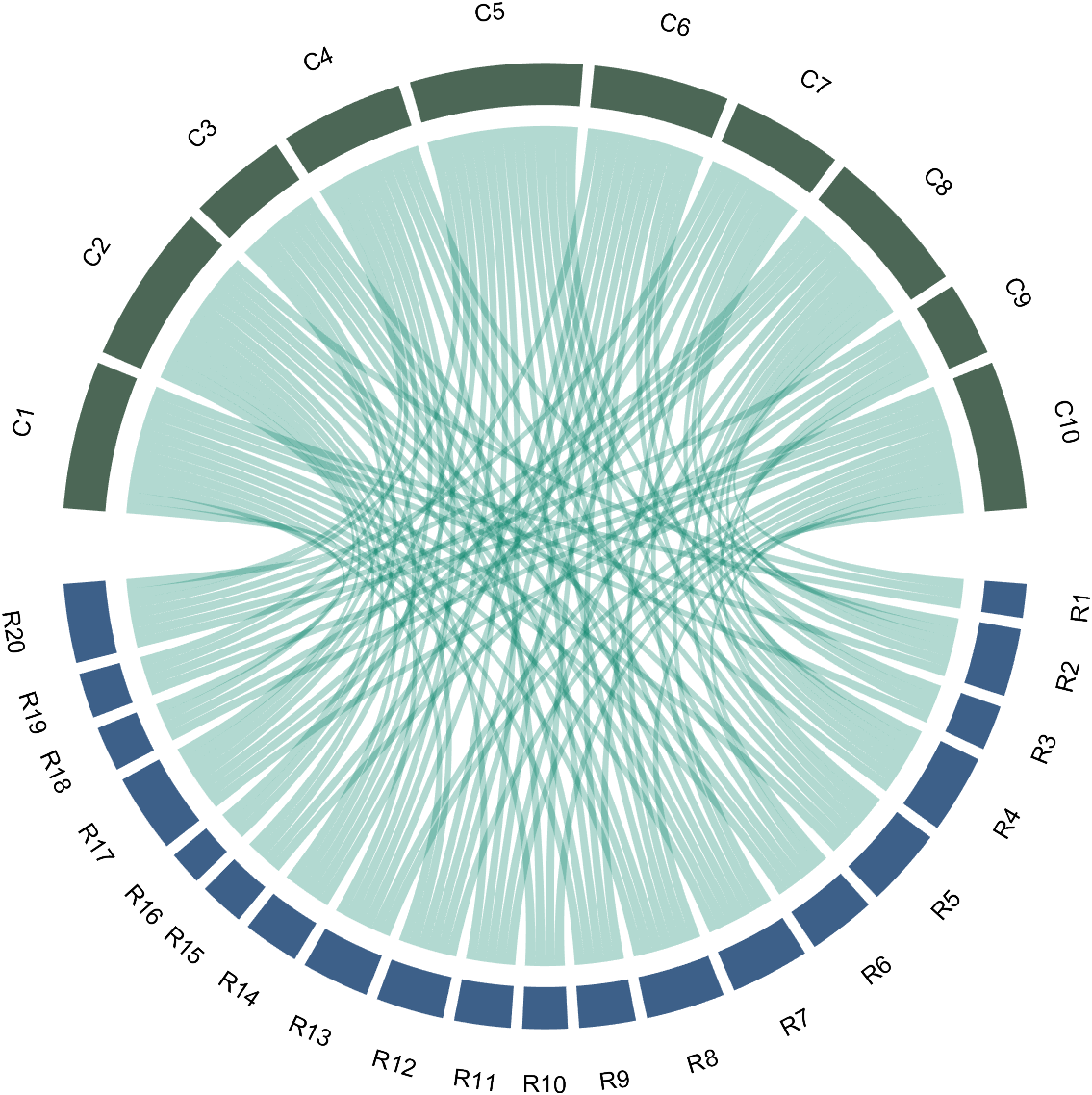

7 Modify Text Direction

dataMat=randi([0,1],[20,10]);

% use Sep to decrease space (separation)

% 使用 sep 减小空隙

CC=chordChart(dataMat,'Sep',1/120);

CC=CC.draw();

CC.tickState('on')

% version 1.7.0更新

% 函数labelRatato用来旋转标签

% The function labelRatato is used to rotate the label

CC.labelRotate('on')

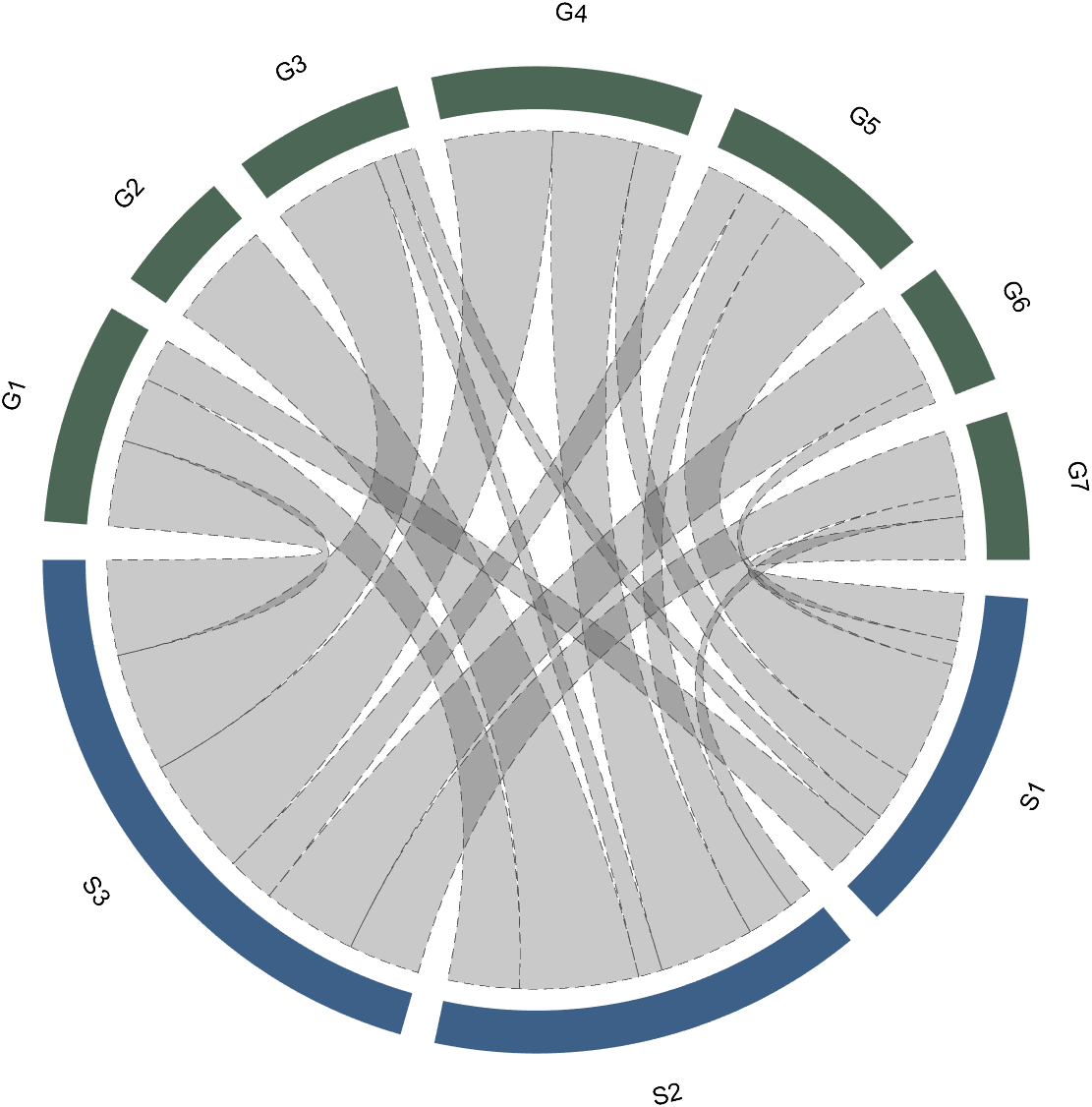

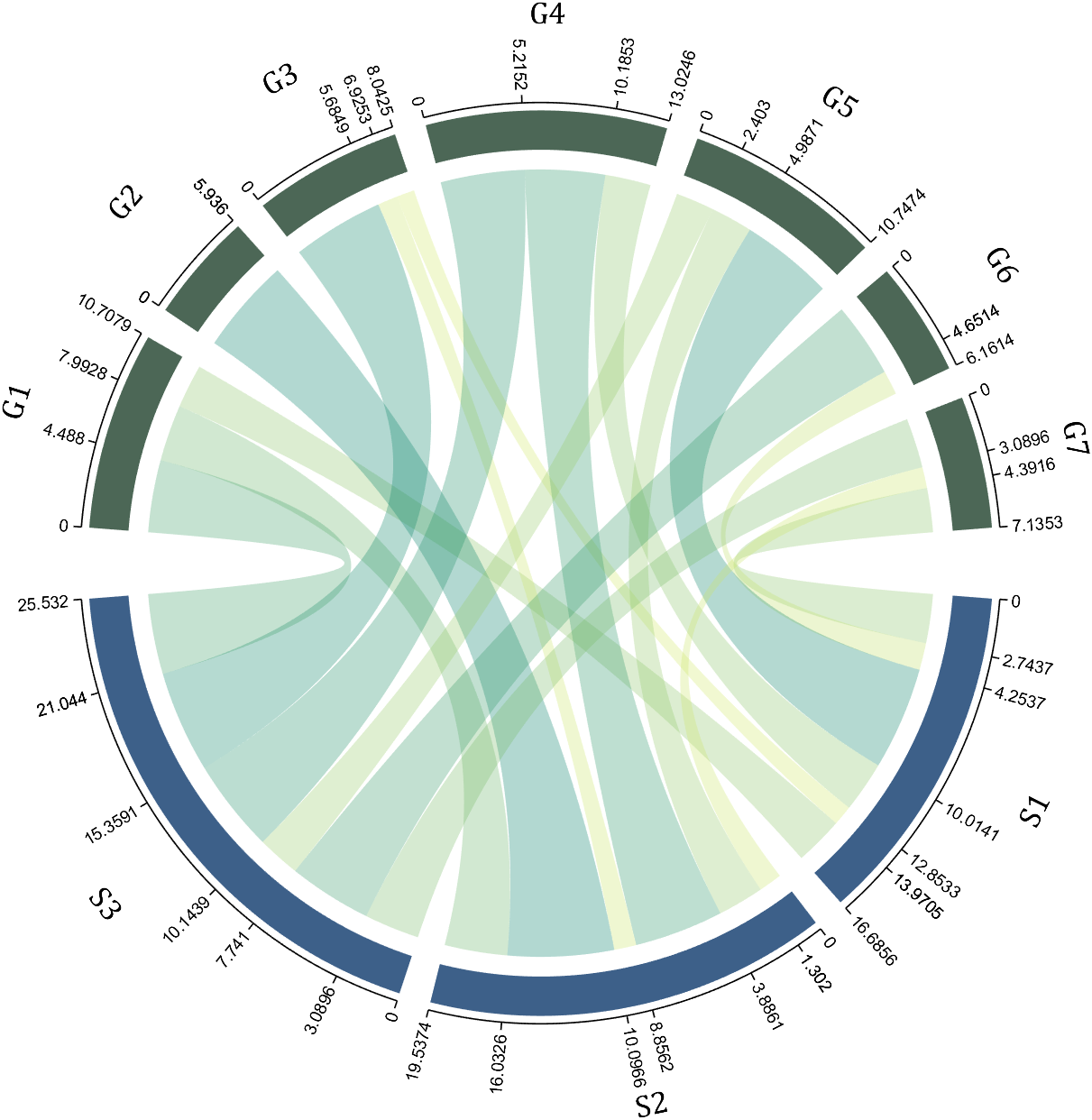

8 Add Tick Labels

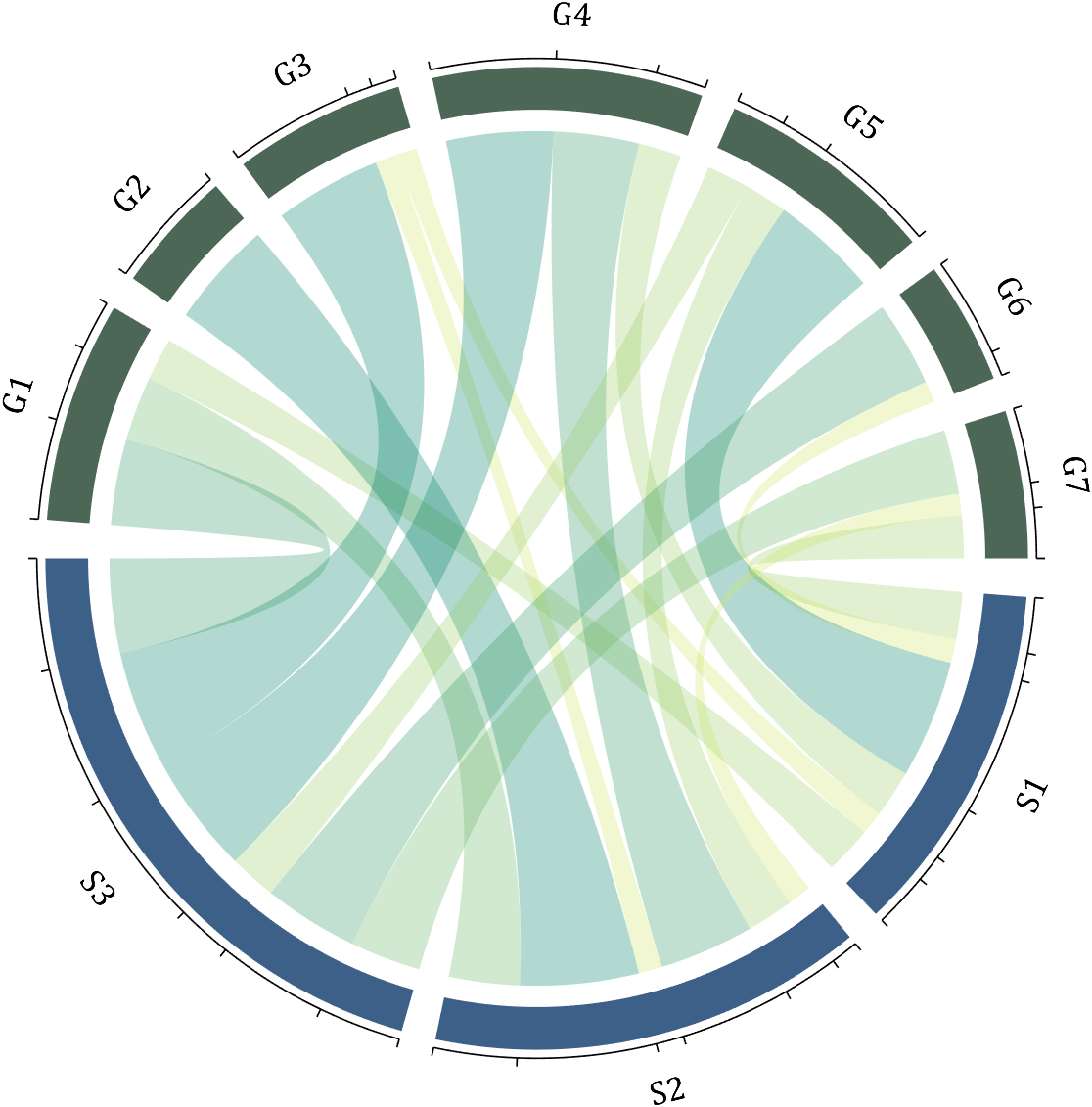

dataMat=[2 0 1 2 5 1 2;

3 5 1 4 2 0 1;

4 0 5 5 2 4 3];

colName={'G1','G2','G3','G4','G5','G6','G7'};

rowName={'S1','S2','S3'};

CC=chordChart(dataMat,'rowName',rowName,'colName',colName);

CC=CC.draw();

CC.setFont('FontSize',17,'FontName','Cambria')

% 显示刻度和数值

% Displays scales and numeric values

CC.tickState('on')

CC.tickLabelState('on')

% 调节标签半径

% Adjustable Label radius

CC.setLabelRadius(1.3);

% figure()

% dataMat=[2 0 1 2 5 1 2;

% 3 5 1 4 2 0 1;

% 4 0 5 5 2 4 3];

% dataMat=dataMat+rand(3,7);

% dataMat(dataMat<1)=0;

%

% CC=chordChart(dataMat,'rowName',rowName,'colName',colName);

% CC=CC.draw();

% CC.setFont('FontSize',17,'FontName','Cambria')

%

% % 显示刻度和数值

% % Displays scales and numeric values

% CC.tickState('on')

% CC.tickLabelState('on')

%

% % 调节标签半径

% % Adjustable Label radius

% CC.setLabelRadius(1.4);

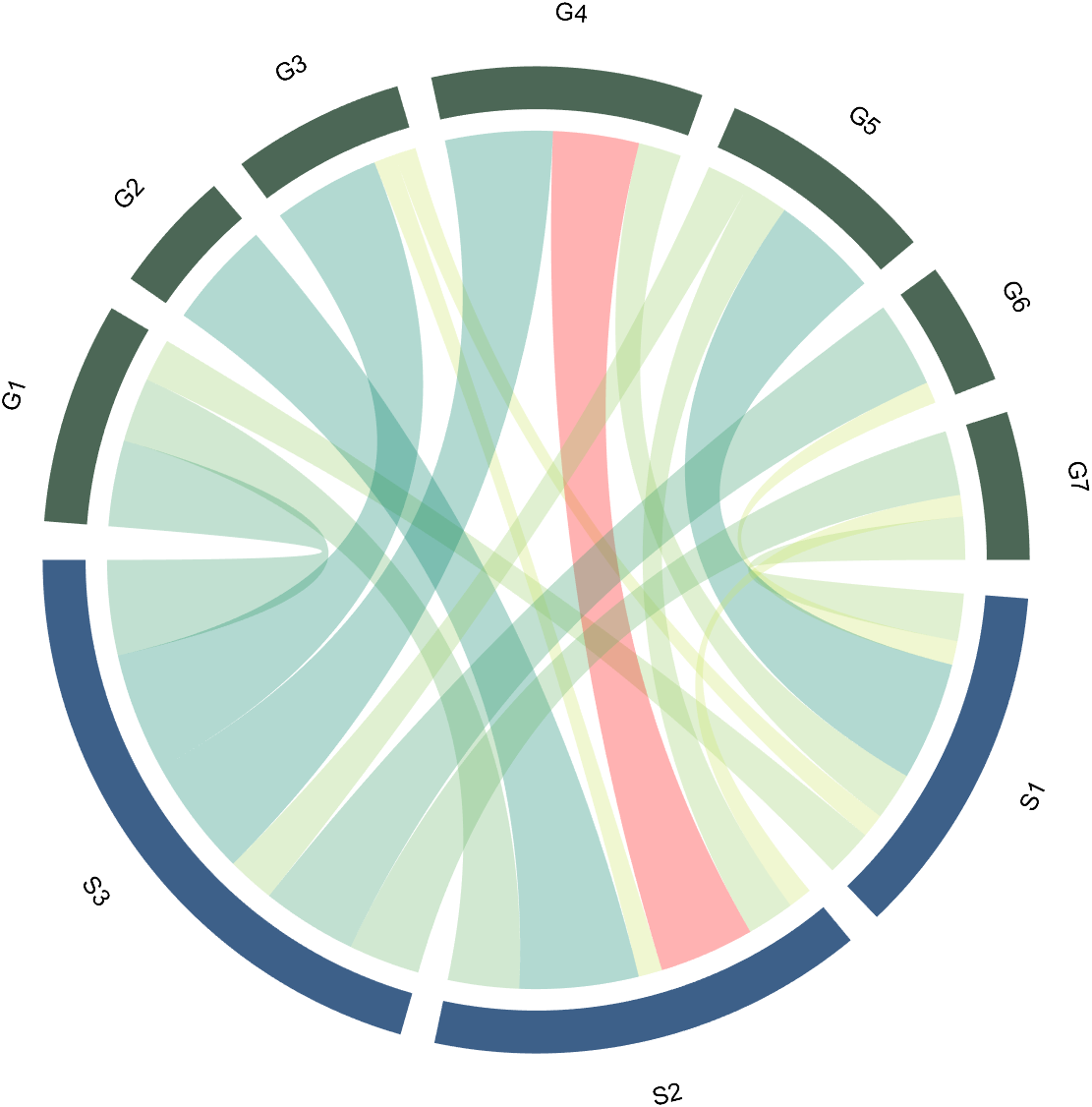

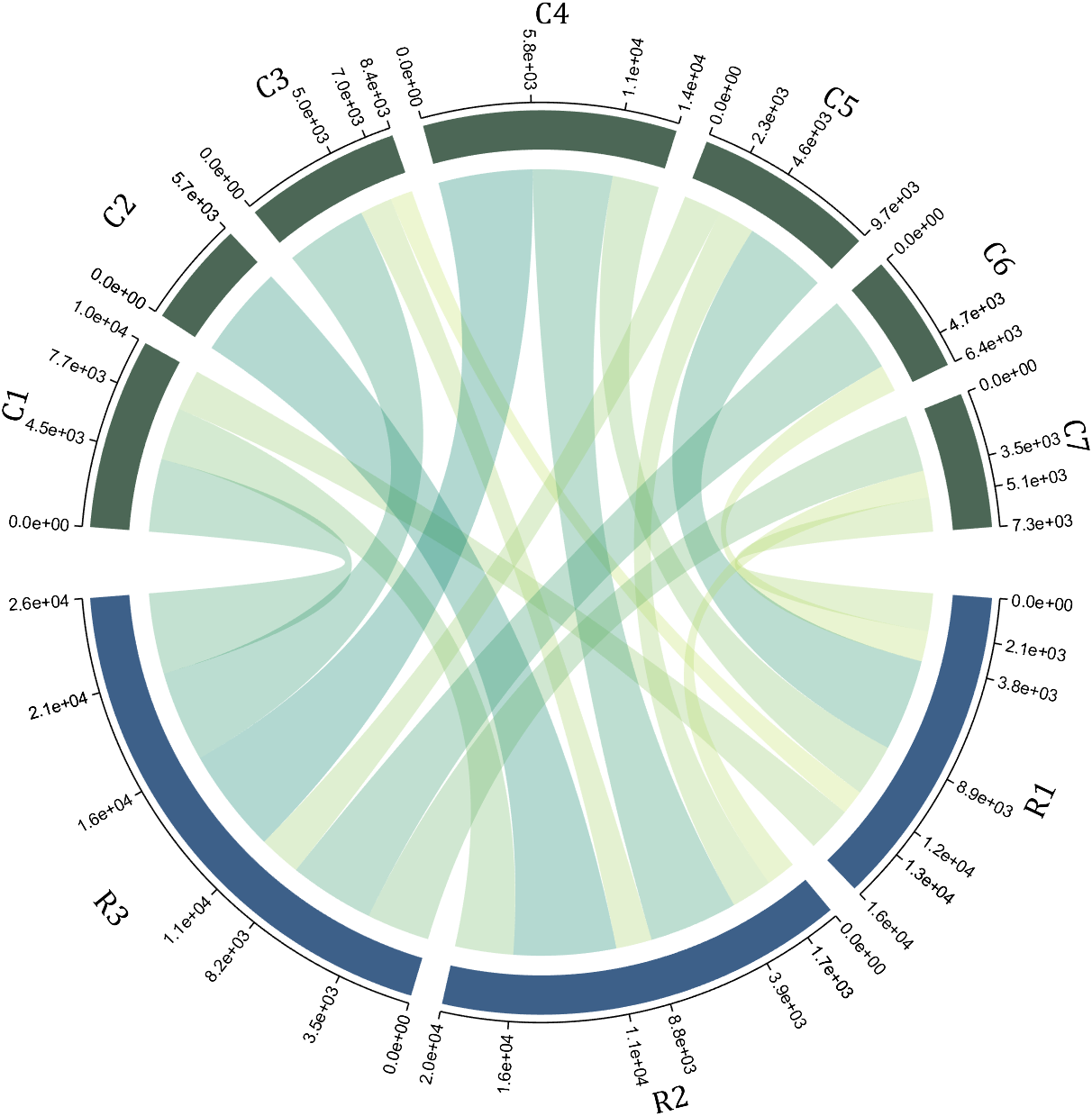

9 Custom Tick Label Format

A function handle is required to input numeric output strings. The format can be set through the setTickLabelFormat function, such as Scientific notation:

dataMat=[2 0 1 2 5 1 2;

3 5 1 4 2 0 1;

4 0 5 5 2 4 3];

dataMat=dataMat+rand(3,7);

dataMat(dataMat<1)=0;

dataMat=dataMat.*1000;

CC=chordChart(dataMat);

CC=CC.draw();

CC.setFont('FontSize',17,'FontName','Cambria')

% 显示刻度和数值

% Displays scales and numeric values

CC.tickState('on')

CC.tickLabelState('on')

% 调节标签半径

% Adjustable Label radius

CC.setLabelRadius(1.4);

% 调整数值字符串格式

% Adjust numeric string format

CC.setTickLabelFormat(@(x)sprintf('%0.1e',x))

10 A Demo

rng(2)

dataMat=randi([1,7],[11,5]);

colName={'Fly','Beetle','Leaf','Soil','Waxberry'};

rowName={'Bartomella','Bradyrhizobium','Dysgomonas','Enterococcus',...

'Lactococcus','norank','others','Pseudomonas','uncultured',...

'Vibrionimonas','Wolbachia'};

CC=chordChart(dataMat,'rowName',rowName,'colName',colName,'Sep',1/80);

CC=CC.draw();

% 修改上方方块颜色(Modify the color of the blocks above)

CListT=[0.7765 0.8118 0.5216;0.4431 0.4706 0.3843;0.5804 0.2275 0.4549;

0.4471 0.4039 0.6745;0.0157 0 0 ];

for i=1:5

CC.setSquareT_N(i,'FaceColor',CListT(i,:))

end

% 修改下方方块颜色(Modify the color of the blocks below)

CListF=[0.5843 0.6863 0.7843;0.1098 0.1647 0.3255;0.0902 0.1608 0.5373;

0.6314 0.7961 0.2118;0.0392 0.2078 0.1059;0.0157 0 0 ;

0.8549 0.9294 0.8745;0.3882 0.3255 0.4078;0.5020 0.7216 0.3843;

0.0902 0.1843 0.1804;0.8196 0.2314 0.0706];

for i=1:11

CC.setSquareF_N(i,'FaceColor',CListF(i,:))

end

% 修改弦颜色(Modify chord color)

for i=1:5

for j=1:11

CC.setChordMN(j,i,'FaceColor',CListT(i,:),'FaceAlpha',.5)

end

end

CC.tickState('on')

CC.labelRotate('on')

CC.setFont('FontSize',17,'FontName','Cambria')

Hope to have your Reviews and Stars!!!

↓ ↓ ↓ ↓ ↓ ↓ ↓ ↓ ↓ ↓

↑ ↑ ↑ ↑ ↑ ↑ ↑ ↑ ↑ ↑

chord chart 弦图

plot beautiful chord chart 好看的弦图绘制

Most of my projects are the tension between what exists and what I must create to make the project work. The more I leverage what exists, the faster I can complete my project in a shorter amount of time. I often find out later in the process that a MATLAB function already exists and has existed for 10 releases. The faster that I discover built-in functions, the faster I can get to the new stuff that I have to invent.

I asked the AI Chat Playground why to use MATLAB's builtin functions and I got some interesting ideas. What are your thoughts?

AI Chat Playground:

- Efficiency and Performance: MATLAB's built-in functions are highly optimized for performance. They are written in optimized and compiled languages like C or C++, which means they run faster than equivalent functions written directly in MATLAB language. When you use these functions, your code can execute more efficiently, which is especially beneficial for handling large datasets or complex mathematical computations.

- Reliability and Stability: Built-in functions have been rigorously tested and debugged by the developers at MathWorks (the company behind MATLAB). They are less likely to contain errors compared to custom-written code, which means you can rely on them to produce accurate and consistent results.

- Ease of Use: Built-in functions are designed to be user-friendly, with clear documentation and support materials available. This can make it easier to perform complex operations without needing a deep understanding of the underlying algorithms. It also reduces the amount of code you need to write and debug, saving time and reducing the potential for errors.

- Compatibility: Built-in functions are updated alongside MATLAB itself, ensuring compatibility with new features and versions of the software. Using built-in functions can help ensure that your code continues to work correctly as MATLAB evolves.

- Advanced Features: MATLAB’s built-in functions often include advanced features and options that are not readily available or would be difficult to implement on your own. For example, MATLAB’s mathematical functions can handle a wide range of special cases and data types, providing more flexibility than custom implementations.

- Community and Support: Using built-in functions means you're working with standard tools recognized by the MATLAB community. This can make it easier to get help from other users or from MathWorks support, as more people will be familiar with the functionality and potential issues of these functions.

Given a vector v whose order we would like to randomly permute, many would perform the permutation by explicitly querying the length/size of v, e.g.,

I=randperm(numel(v));

v=v(I);

However, one can instead do as follows, avoiding the size query.

v=v(randperm(end))

Analogous things can be done with matrices, e.g.,

A=A(randperm(end), randperm(end));

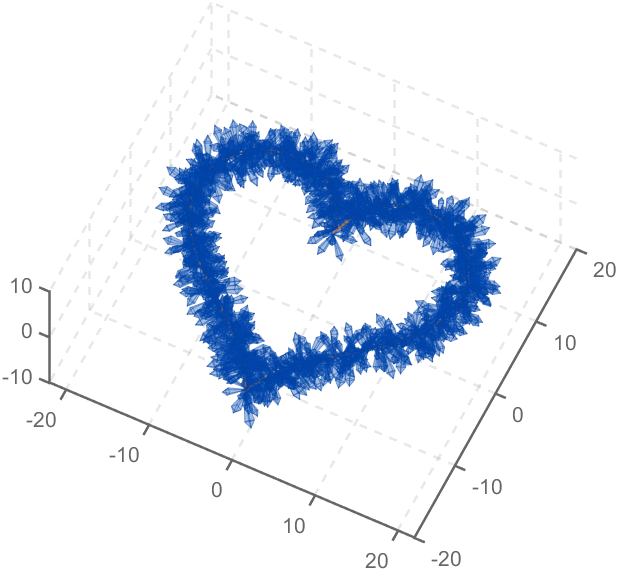

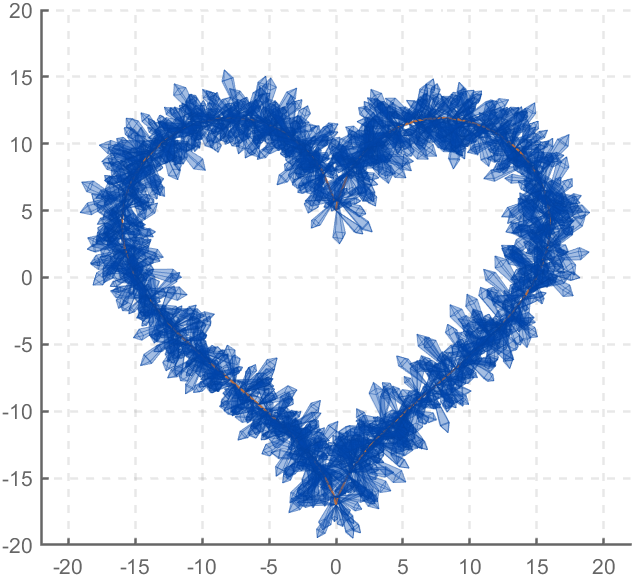

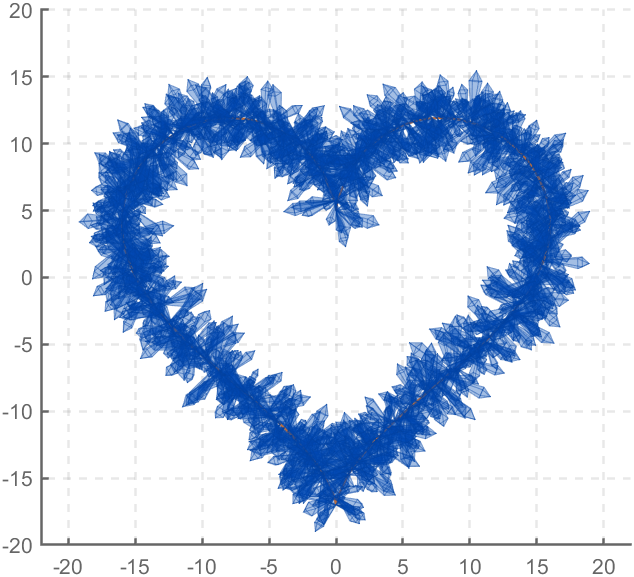

The creativity comes from the copper sulfate crystal heart made in junior high school. Copper sulfate is a triclinic crystal, and the same structure was not used here for convenience in drawing.

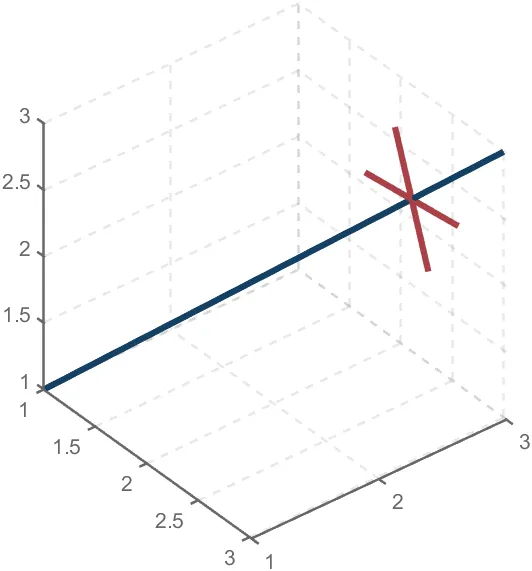

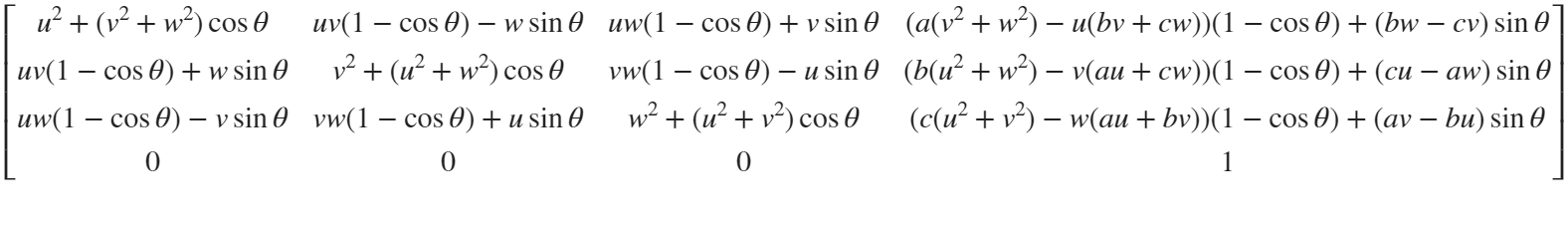

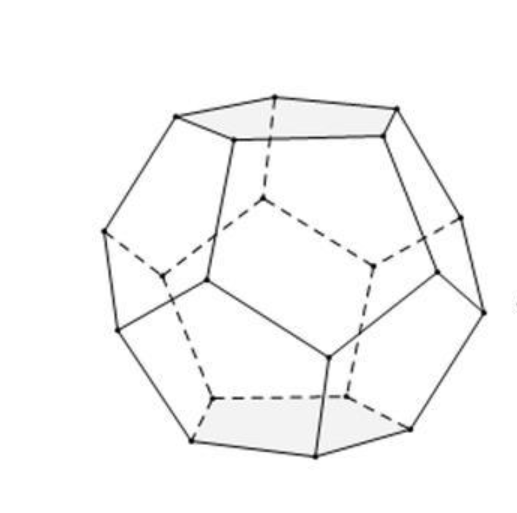

Part 1. Coordinate transformation

To draw a crystal heart, one must first be able to draw crystal clusters. To draw a crystal cluster, one must first be able to draw a crystal. To draw a crystal, we need this kind of structure:

We first need a point with a certain distance from the straight line and a perpendicular point of cutPnt, which is very easy to find, for example, cutPnt=[x0, y0, z0]; The direction of the central axis is V=[x1, y1, z1]; If the distance to the straight line is L, the following points clearly meet the conditions:

v2=[z1,z1,-x1-y1];

v2=v2./norm(v2).*L;

pnt=cutPnt+v2;

But finding only one point is not enough. We need to find four points, and each point is obtained by rotating the previous point around a straight line by  degrees. Therefore, we need to obtain our point rotation transformation matrix around a straight line

degrees. Therefore, we need to obtain our point rotation transformation matrix around a straight line

quite complex,right?

rotateMat=[u^2+(v^2+w^2)*cos(theta) , u*v*(1-cos(theta))-w*sin(theta), u*w*(1-cos(theta))+v*sin(theta), (a*(v^2+w^2)-u*(b*v+c*w))*(1-cos(theta))+(b*w-c*v)*sin(theta);

u*v*(1-cos(theta))+w*sin(theta), v^2+(u^2+w^2)*cos(theta) , v*w*(1-cos(theta))-u*sin(theta), (b*(u^2+w^2)-v*(a*u+c*w))*(1-cos(theta))+(c*u-a*w)*sin(theta);

u*w*(1-cos(theta))-v*sin(theta), v*w*(1-cos(theta))+u*sin(theta), w^2+(u^2+v^2)*cos(theta) , (c*(u^2+v^2)-w*(a*u+b*v))*(1-cos(theta))+(a*v-b*u)*sin(theta);

0 , 0 , 0 , 1];

Where [u, v, w] is the directional unit vector, and [a, b, c] is the initial coordinate of the axis:

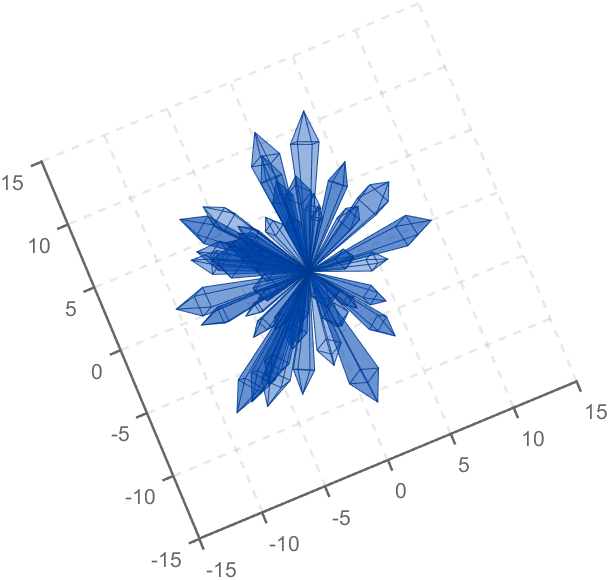

Part 2. Crystal Cluster Drawing

function crystall

hold on

for i=1:50

len=rand(1)*8+5;

tempV=rand(1,3)-0.5;

tempV(3)=abs(tempV(3));

tempV=tempV./norm(tempV).*len;

tempEpnt=tempV;

drawCrystal([0 0 0],tempEpnt,pi/6,0.8,0.1,rand(1).*0.2+0.2)

disp(i)

end

ax=gca;

ax.XLim=[-15,15];

ax.YLim=[-15,15];

ax.ZLim=[-2,15];

grid on

ax.GridLineStyle='--';

ax.LineWidth=1.2;

ax.XColor=[1,1,1].*0.4;

ax.YColor=[1,1,1].*0.4;

ax.ZColor=[1,1,1].*0.4;

ax.DataAspectRatio=[1,1,1];

ax.DataAspectRatioMode='manual';

ax.CameraPosition=[-67.6287 -204.5276 82.7879];

function drawCrystal(Spnt,Epnt,theta,cl,w,alpha)

%plot3([Spnt(1),Epnt(1)],[Spnt(2),Epnt(2)],[Spnt(3),Epnt(3)])

mainV=Epnt-Spnt;

cutPnt=cl.*(mainV)+Spnt;

cutV=[mainV(3),mainV(3),-mainV(1)-mainV(2)];

cutV=cutV./norm(cutV).*w.*norm(mainV);

cornerPnt=cutPnt+cutV;

cornerPnt=rotateAxis(Spnt,Epnt,cornerPnt,theta);

cornerPntSet(1,:)=cornerPnt';

for ii=1:3

cornerPnt=rotateAxis(Spnt,Epnt,cornerPnt,pi/2);

cornerPntSet(ii+1,:)=cornerPnt';

end

F = [1,3,4;1,4,5;1,5,6;1,6,3;...

2,3,4;2,4,5;2,5,6;2,6,3];

V = [Spnt;Epnt;cornerPntSet];

patch('Faces',F,'Vertices',V,'FaceColor',[0 71 177]./255,...

'FaceAlpha',alpha,'EdgeColor',[0 71 177]./255.*0.8,...

'EdgeAlpha',0.6,'LineWidth',0.5,'EdgeLighting',...

'gouraud','SpecularStrength',0.3)

end

function newPnt=rotateAxis(Spnt,Epnt,cornerPnt,theta)

V=Epnt-Spnt;V=V./norm(V);

u=V(1);v=V(2);w=V(3);

a=Spnt(1);b=Spnt(2);c=Spnt(3);

cornerPnt=[cornerPnt(:);1];

rotateMat=[u^2+(v^2+w^2)*cos(theta) , u*v*(1-cos(theta))-w*sin(theta), u*w*(1-cos(theta))+v*sin(theta), (a*(v^2+w^2)-u*(b*v+c*w))*(1-cos(theta))+(b*w-c*v)*sin(theta);

u*v*(1-cos(theta))+w*sin(theta), v^2+(u^2+w^2)*cos(theta) , v*w*(1-cos(theta))-u*sin(theta), (b*(u^2+w^2)-v*(a*u+c*w))*(1-cos(theta))+(c*u-a*w)*sin(theta);

u*w*(1-cos(theta))-v*sin(theta), v*w*(1-cos(theta))+u*sin(theta), w^2+(u^2+v^2)*cos(theta) , (c*(u^2+v^2)-w*(a*u+b*v))*(1-cos(theta))+(a*v-b*u)*sin(theta);

0 , 0 , 0 , 1];

newPnt=rotateMat*cornerPnt;

newPnt(4)=[];

end

end

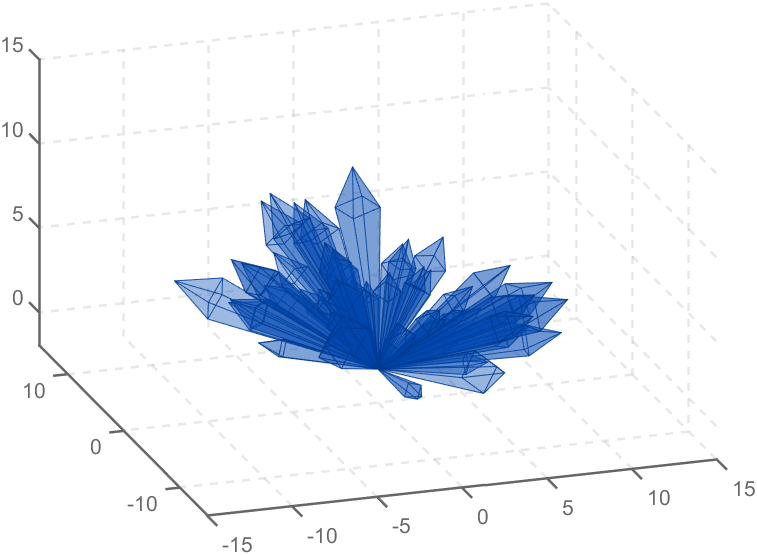

Part 3. Drawing of Crystal Heart

function crystalHeart

clc;clear;close all

hold on

% drawCrystal([1,1,1],[3,3,3],pi/6,0.8,0.14)

sep=pi/8;

t=[0:0.2:sep,sep:0.02:pi-sep,pi-sep:0.2:pi+sep,pi+sep:0.02:2*pi-sep,2*pi-sep:0.2:2*pi];

x=16*sin(t).^3;

y=13*cos(t)-5*cos(2*t)-2*cos(3*t)-cos(4*t);

z=zeros(size(t));

plot3(x,y,z,'Color',[186,110,64]./255,'LineWidth',1)

for i=1:length(t)

for j=1:6

len=rand(1)*2.5+1.5;

tempV=rand(1,3)-0.5;

tempV=tempV./norm(tempV).*len;

tempSpnt=[x(i),y(i),z(i)];

tempEpnt=tempV+tempSpnt;

drawCrystal(tempSpnt,tempEpnt,pi/6,0.8,0.14)

disp([i,j])

end

end

ax=gca;

ax.XLim=[-22,22];

ax.YLim=[-20,20];

ax.ZLim=[-10,10];

grid on

ax.GridLineStyle='--';

ax.LineWidth=1.2;

ax.XColor=[1,1,1].*0.4;

ax.YColor=[1,1,1].*0.4;

ax.ZColor=[1,1,1].*0.4;

ax.DataAspectRatio=[1,1,1];

ax.DataAspectRatioMode='manual';

function drawCrystal(Spnt,Epnt,theta,cl,w)

%plot3([Spnt(1),Epnt(1)],[Spnt(2),Epnt(2)],[Spnt(3),Epnt(3)])

mainV=Epnt-Spnt;

cutPnt=cl.*(mainV)+Spnt;

cutV=[mainV(3),mainV(3),-mainV(1)-mainV(2)];

cutV=cutV./norm(cutV).*w.*norm(mainV);

cornerPnt=cutPnt+cutV;

cornerPnt=rotateAxis(Spnt,Epnt,cornerPnt,theta);

cornerPntSet(1,:)=cornerPnt';

for ii=1:3

cornerPnt=rotateAxis(Spnt,Epnt,cornerPnt,pi/2);

cornerPntSet(ii+1,:)=cornerPnt';

end

F = [1,3,4;1,4,5;1,5,6;1,6,3;...

2,3,4;2,4,5;2,5,6;2,6,3];

V = [Spnt;Epnt;cornerPntSet];

patch('Faces',F,'Vertices',V,'FaceColor',[0 71 177]./255,...

'FaceAlpha',0.2,'EdgeColor',[0 71 177]./255.*0.9,...

'EdgeAlpha',0.25,'LineWidth',0.01,'EdgeLighting',...

'gouraud','SpecularStrength',0.3)

end

function newPnt=rotateAxis(Spnt,Epnt,cornerPnt,theta)

V=Epnt-Spnt;V=V./norm(V);

u=V(1);v=V(2);w=V(3);

a=Spnt(1);b=Spnt(2);c=Spnt(3);

cornerPnt=[cornerPnt(:);1];

rotateMat=[u^2+(v^2+w^2)*cos(theta) , u*v*(1-cos(theta))-w*sin(theta), u*w*(1-cos(theta))+v*sin(theta), (a*(v^2+w^2)-u*(b*v+c*w))*(1-cos(theta))+(b*w-c*v)*sin(theta);

u*v*(1-cos(theta))+w*sin(theta), v^2+(u^2+w^2)*cos(theta) , v*w*(1-cos(theta))-u*sin(theta), (b*(u^2+w^2)-v*(a*u+c*w))*(1-cos(theta))+(c*u-a*w)*sin(theta);

u*w*(1-cos(theta))-v*sin(theta), v*w*(1-cos(theta))+u*sin(theta), w^2+(u^2+v^2)*cos(theta) , (c*(u^2+v^2)-w*(a*u+b*v))*(1-cos(theta))+(a*v-b*u)*sin(theta);

0 , 0 , 0 , 1];

newPnt=rotateMat*cornerPnt;

newPnt(4)=[];

end

end

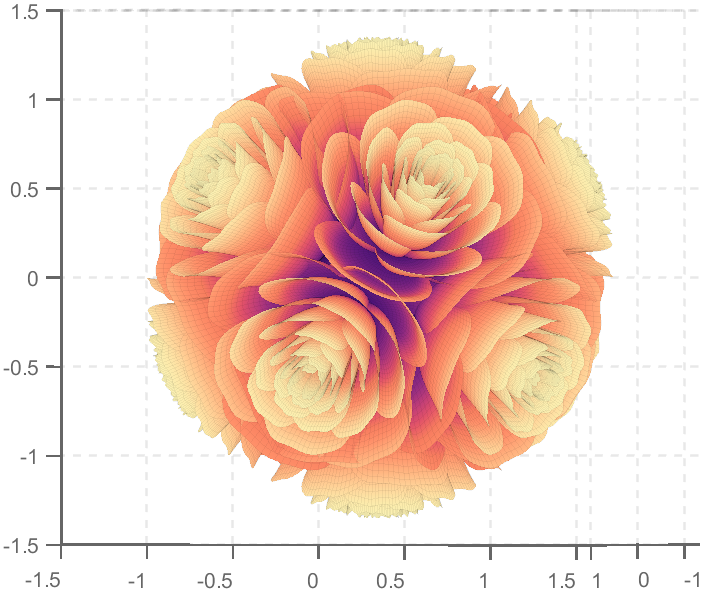

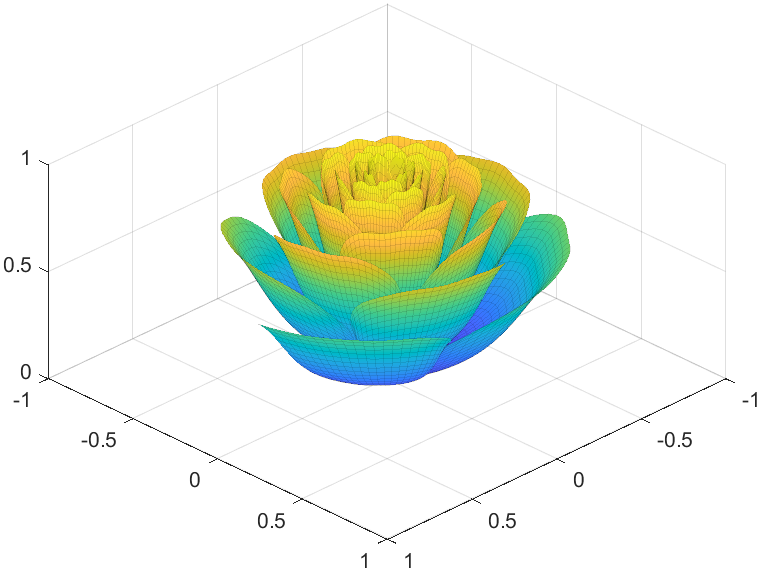

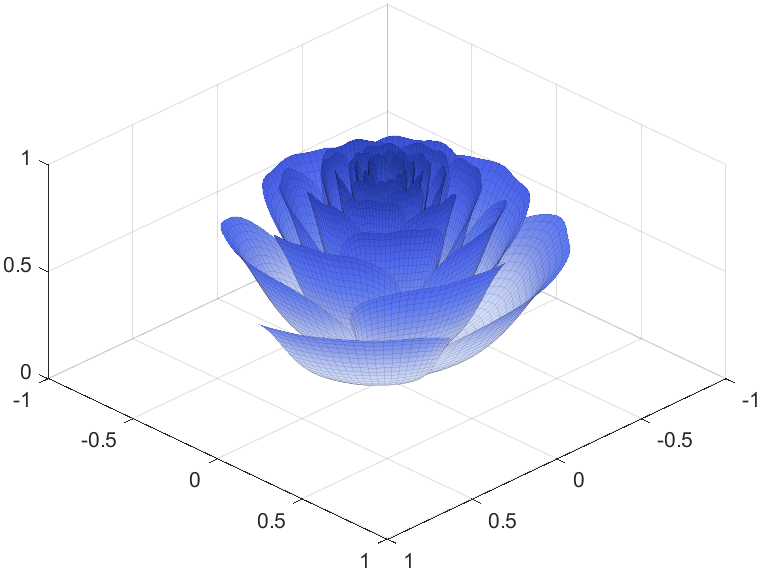

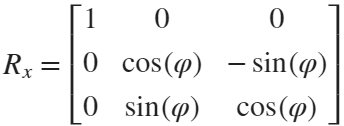

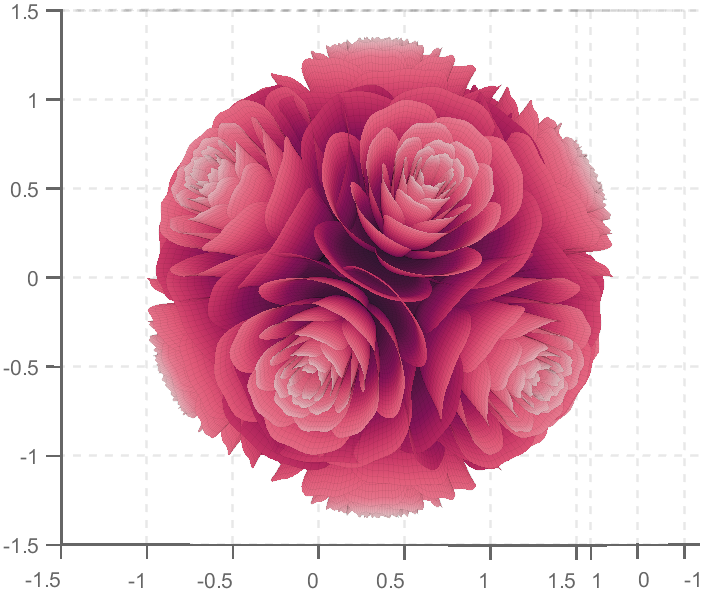

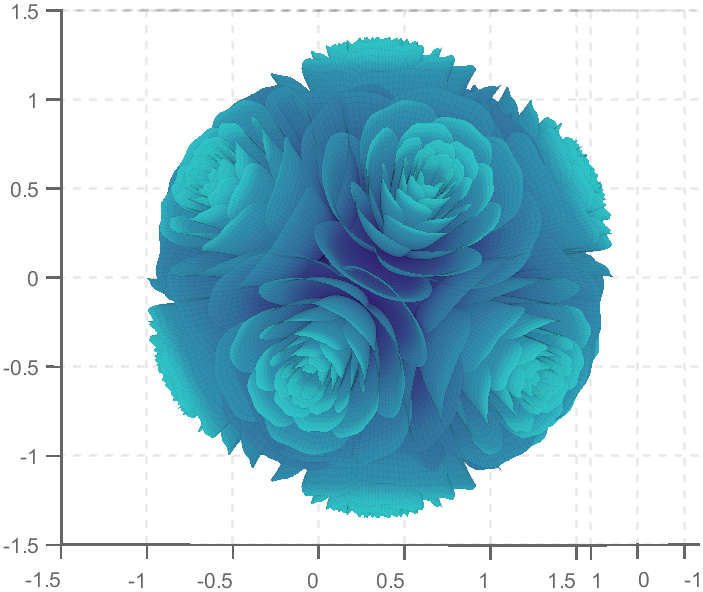

So, how to draw a roseball just like this ?

To begin with, we need to know how to draw a single rose in MATLAB:

function drawrose

set(gca,'CameraPosition',[2 2 2])

hold on

grid on

[x,t]=meshgrid((0:24)./24,(0:0.5:575)./575.*20.*pi+4*pi);

p=(pi/2)*exp(-t./(8*pi));

change=sin(15*t)/150;

u=1-(1-mod(3.6*t,2*pi)./pi).^4./2+change;

y=2*(x.^2-x).^2.*sin(p);

r=u.*(x.*sin(p)+y.*cos(p));

h=u.*(x.*cos(p)-y.*sin(p));

surface(r.*cos(t),r.*sin(t),h,'EdgeAlpha',0.1,...

'EdgeColor',[0 0 0],'FaceColor','interp')

end

Tts pretty easy, Now we are trying to dye it the desired color:

function drawrose

set(gca,'CameraPosition',[2 2 2])

hold on

grid on

[x,t]=meshgrid((0:24)./24,(0:0.5:575)./575.*20.*pi+4*pi);

p=(pi/2)*exp(-t./(8*pi));

change=sin(15*t)/150;

u=1-(1-mod(3.6*t,2*pi)./pi).^4./2+change;

y=2*(x.^2-x).^2.*sin(p);

r=u.*(x.*sin(p)+y.*cos(p));

h=u.*(x.*cos(p)-y.*sin(p));

map=[0.9176 0.9412 1.0000

0.8353 0.8706 0.9922

0.8196 0.8627 0.9804

0.7020 0.7569 0.9412

0.5176 0.5882 0.9255

0.3686 0.4824 0.9412

0.3059 0.4000 0.9333

0.2275 0.3176 0.8353

0.1216 0.2275 0.6471];

Xi=1:size(map,1);Xq=linspace(1,size(map,1),100);

map=[interp1(Xi,map(:,1),Xq,'linear')',...

interp1(Xi,map(:,2),Xq,'linear')',...

interp1(Xi,map(:,3),Xq,'linear')'];

surface(r.*cos(t),r.*sin(t),h,'EdgeAlpha',0.1,...

'EdgeColor',[0 0 0],'FaceColor','interp')

colormap(map)

end

I try to take colors from real roses and interpolate them to make them more realistic

Then, how can I put these colorful flowers on to a ball ?

We need to place the drawn flowers on each face of the polyhedron sphere through coordinate transformation. Here, we use a regular dodecahedron:

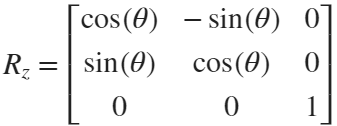

Move the flower using the following rotation formula:

We place a flower on each plane, which means that the angle between every two flowers is  degrees. We can place each flower at the appropriate angle through multiple x-axis rotations and multiple z-axis rotations. The code is as follows:

degrees. We can place each flower at the appropriate angle through multiple x-axis rotations and multiple z-axis rotations. The code is as follows:

function roseBall(colorList)

%曲面数据计算

%==========================================================================

[x,t]=meshgrid((0:24)./24,(0:0.5:575)./575.*20.*pi+4*pi);

p=(pi/2)*exp(-t./(8*pi));

change=sin(15*t)/150;

u=1-(1-mod(3.6*t,2*pi)./pi).^4./2+change;

y=2*(x.^2-x).^2.*sin(p);

r=u.*(x.*sin(p)+y.*cos(p));

h=u.*(x.*cos(p)-y.*sin(p));

%颜色映射表

%==========================================================================

hMap=(h-min(min(h)))./(max(max(h))-min(min(h)));

col=size(hMap,2);

if nargin<1

colorList=[0.0200 0.0400 0.3900

0 0.0900 0.5800

0 0.1300 0.6400

0.0200 0.0600 0.6900

0 0.0800 0.7900

0.0100 0.1800 0.8500

0 0.1300 0.9600

0.0100 0.2600 0.9900

0 0.3500 0.9900

0.0700 0.6200 1.0000

0.1700 0.6900 1.0000];

end

colorFunc=colorFuncFactory(colorList);

dataMap=colorFunc(hMap');

colorMap(:,:,1)=dataMap(:,1:col);

colorMap(:,:,2)=dataMap(:,col+1:2*col);

colorMap(:,:,3)=dataMap(:,2*col+1:3*col);

function colorFunc=colorFuncFactory(colorList)

xx=(0:size(colorList,1)-1)./(size(colorList,1)-1);

y1=colorList(:,1);y2=colorList(:,2);y3=colorList(:,3);

colorFunc=@(X)[interp1(xx,y1,X,'linear')',interp1(xx,y2,X,'linear')',interp1(xx,y3,X,'linear')'];

end

%曲面旋转及绘制

%==========================================================================

surface(r.*cos(t),r.*sin(t),h+0.35,'EdgeAlpha',0.05,...

'EdgeColor',[0 0 0],'FaceColor','interp','CData',colorMap)

hold on

surface(r.*cos(t),r.*sin(t),-h-0.35,'EdgeAlpha',0.05,...

'EdgeColor',[0 0 0],'FaceColor','interp','CData',colorMap)

Xset=r.*cos(t);

Yset=r.*sin(t);

Zset=h+0.35;

yaw_z=72*pi/180;

roll_x=pi-acos(-1/sqrt(5));

R_z_2=[cos(yaw_z),-sin(yaw_z),0;

sin(yaw_z),cos(yaw_z),0;

0,0,1];

R_z_1=[cos(yaw_z/2),-sin(yaw_z/2),0;

sin(yaw_z/2),cos(yaw_z/2),0;

0,0,1];

R_x_2=[1,0,0;

0,cos(roll_x),-sin(roll_x);

0,sin(roll_x),cos(roll_x)];

[nX,nY,nZ]=rotateXYZ(Xset,Yset,Zset,R_x_2);

surface(nX,nY,nZ,'EdgeAlpha',0.05,...

'EdgeColor',[0 0 0],'FaceColor','interp','CData',colorMap)

for k=1:4

[nX,nY,nZ]=rotateXYZ(nX,nY,nZ,R_z_2);

surface(nX,nY,nZ,'EdgeAlpha',0.05,...

'EdgeColor',[0 0 0],'FaceColor','interp','CData',colorMap)

end

[nX,nY,nZ]=rotateXYZ(nX,nY,nZ,R_z_1);

for k=1:5

[nX,nY,nZ]=rotateXYZ(nX,nY,nZ,R_z_2);

surface(nX,nY,-nZ,'EdgeAlpha',0.05,...

'EdgeColor',[0 0 0],'FaceColor','interp','CData',colorMap)

end

%--------------------------------------------------------------------------

function [nX,nY,nZ]=rotateXYZ(X,Y,Z,R)

nX=zeros(size(X));

nY=zeros(size(Y));

nZ=zeros(size(Z));

for i=1:size(X,1)

for j=1:size(X,2)

v=[X(i,j);Y(i,j);Z(i,j)];

nv=R*v;

nX(i,j)=nv(1);

nY(i,j)=nv(2);

nZ(i,j)=nv(3);

end

end

end

%axes属性调整

%==========================================================================

ax=gca;

grid on

ax.GridLineStyle='--';

ax.LineWidth=1.2;

ax.XColor=[1,1,1].*0.4;

ax.YColor=[1,1,1].*0.4;

ax.ZColor=[1,1,1].*0.4;

ax.DataAspectRatio=[1,1,1];

ax.DataAspectRatioMode='manual';

ax.CameraPosition=[-6.5914 -24.1625 -0.0384];

end

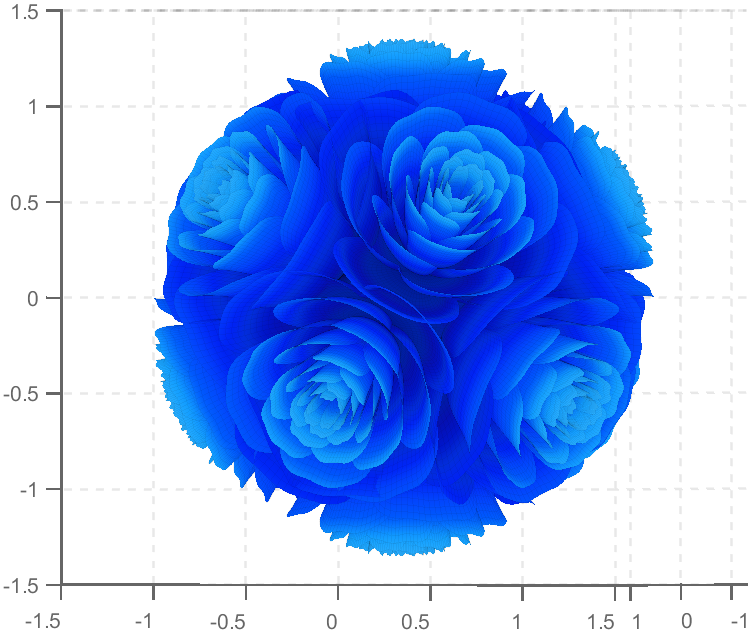

TRY DIFFERENT COLORS !!

colorList1=[0.2000 0.0800 0.4300

0.2000 0.1300 0.4600

0.2000 0.2100 0.5000

0.2000 0.2800 0.5300

0.2000 0.3700 0.5800

0.1900 0.4500 0.6200

0.2000 0.4800 0.6400

0.1900 0.5400 0.6700

0.1900 0.5700 0.6900

0.1900 0.7500 0.7800

0.1900 0.8000 0.8100

];

colorList2=[0.1300 0.1000 0.1600

0.2000 0.0900 0.2000

0.2800 0.0800 0.2300

0.4200 0.0800 0.3000

0.5100 0.0700 0.3400

0.6600 0.1200 0.3500

0.7900 0.2200 0.4000

0.8800 0.3500 0.4700

0.9000 0.4500 0.5400

0.8900 0.7800 0.7900

];

colorList3=[0.3200 0.3100 0.7600

0.3800 0.3400 0.7600

0.5300 0.4200 0.7500

0.6400 0.4900 0.7300

0.7200 0.5500 0.7200

0.7900 0.6100 0.7100

0.9100 0.7100 0.6800

0.9800 0.7600 0.6700

];

colorList4=[0.2100 0.0900 0.3800

0.2900 0.0700 0.4700

0.4000 0.1100 0.4900

0.5500 0.1600 0.5100

0.7500 0.2400 0.4700

0.8900 0.3200 0.4100

0.9700 0.4900 0.3700

1.0000 0.5600 0.4100

1.0000 0.6900 0.4900

1.0000 0.8200 0.5900

0.9900 0.9200 0.6700

0.9800 0.9500 0.7100];

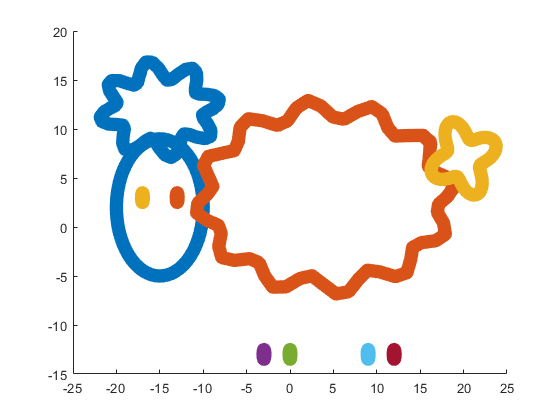

Let us consider how to draw a Happy Sheep. A Happy Sheep was introduced in the MATLAB Mini Hack contest: Happy Sheep!

In this contest there was the strict limitation on the code length. So the code of the Happy Sheep is very compact and is only 280 characters long. We will analyze the process of drawing the Happy Sheep in MATLAB step by step. The explanations of the even more compact version of the code of the same sheep are given below.

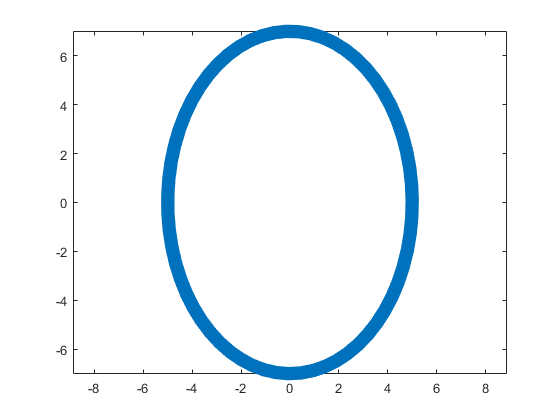

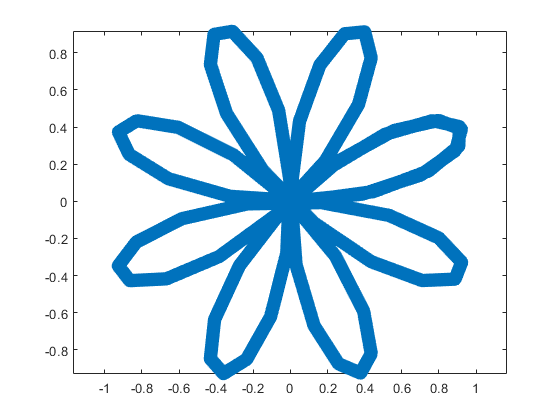

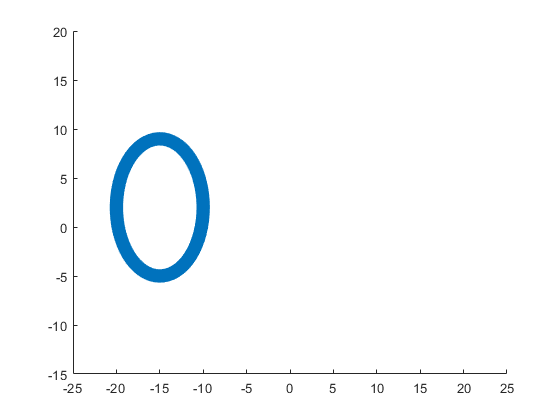

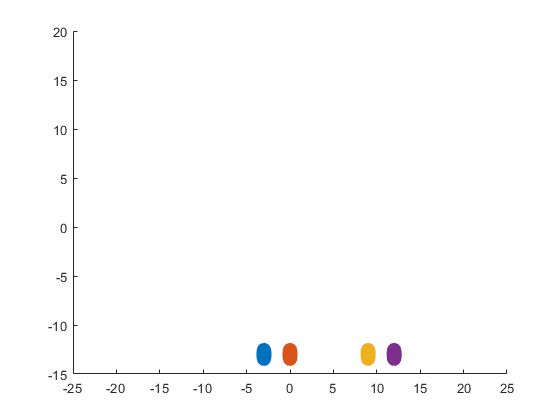

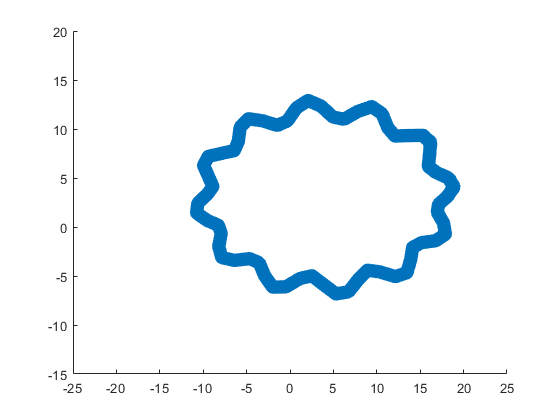

So, how to draw a sheep? It is very easy. We could notice that usually a sheep is covered by crimped wool. Therefore, a sheep could be painted using several geometrical curves of similar types. Of course, then it will be an abstract model of the real sheep. Let us select two mathematical curves, which are the most appropriate for our goal. They are an ellipse for smooth parts of the sheep and an ellipse combined with a rose for woolen parts of the sheep.

Let us recall the mathematical formulas of these curves. A parametric representation of the standard ellipse is the following:

Also we will use the following parametric representation of the rose (rhodonea) curve:

This curve was named by the mathematician Guido Grandi.

Let us combine them in one curve and add possible shifts:

Now if we would like to create an ellipse, we will set  and

and  . If we would like to create a rose, we will set

. If we would like to create a rose, we will set  and

and  . If we would like to shift our curve, we will set

. If we would like to shift our curve, we will set  and

and  to the required values. Of course, we could set all non-zero parameters to combine both chosen curves and use the shifts.

to the required values. Of course, we could set all non-zero parameters to combine both chosen curves and use the shifts.

Let us describe how to create these curves using the MATLAB code. To make the code more compact, it is possible to program both formulas for the combined curve in one line using the anonymous function. We could make the code more compact using the function handles for sine and cosine functions. Then the MATLAB code for an example of the ellipse curve will be the following.

% Handles

s=@sin;

c=@cos;

% Ellipse + Polar Rose

F=@(t,a,f) a(1)*f(t)+s(a(2)*t).*f(t)+a(3);

% Angles

t=0:.1:7;

% Parameters

E = [5 7;0 0;0 0];

% Painting

figure;

plot(F(t,E(:,1),c),F(t,E(:,2),s),'LineWidth',10);

axis equal

The parameter t varies from 0 to 7, which is the nearest integer greater than  , with the step 0.1. The result of this code is the following ellipse curve with

, with the step 0.1. The result of this code is the following ellipse curve with  and

and  .

.

This ellipse is described by the following parametric equations:

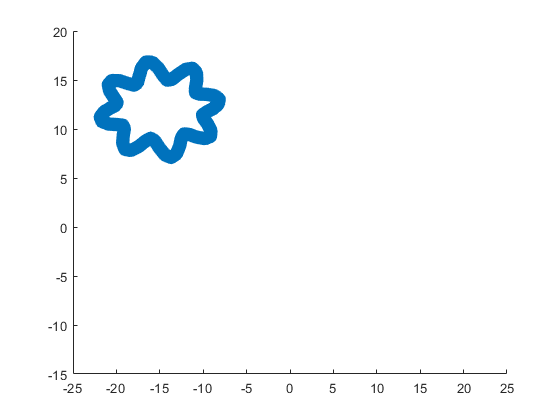

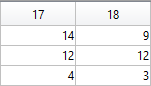

The MATLAB code for an example of the rose curve will be the following.

% Handles

s=@sin;

c=@cos;

% Ellipse + Polar Rose

F=@(t,a,f) a(1)*f(t)+s(a(2)*t).*f(t)+a(3);

% Angles

t=0:.1:7;

% Parameters

R = [0 0;4 4;0 0];

% Painting

figure;

plot(F(t,R(:,1),c),F(t,R(:,2),s),'LineWidth',10);

axis equal

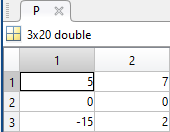

The result of this code is the following rose curve with  and

and  .

.

This rose is described by the following parametric equations:

Obviously, now we are ready to draw main parts of our sheep! As we reproduce an abstract model of the sheep, let us select the following main parts for the representation: head, eyes, hoofs, body, crown, and tail. We will use ellipses for the first three parts in this list and ellipses combined with roses for the last three ones.

First let us describe drawing of each part independently.

The following MATLAB code will be used to do this.

% Handles

s=@sin;

c=@cos;

% Ellipse + Polar Rose

F=@(t,a,f) a(1)*f(t)+s(a(2)*t).*f(t)+a(3);

% Angles

t=0:.1:7;

% Parameters

Head = 1;

Eyes = 2:3;

Hoofs = 4:7;

Body = 8;

Crown = 9;

Tail = 10;

G=-13;

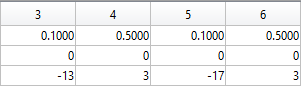

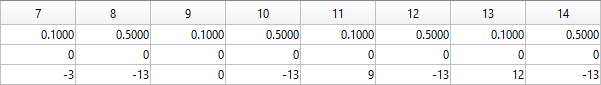

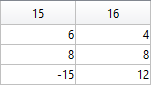

P=[5 7 repmat([.1 .5],1,6) 6 4 14 9 3 3;zeros(1,14) 8 8 12 12 4 4;...

-15 2 G 3 -17 3 -3 G 0 G 9 G 12 G -15 12 4 3 20 7];

% Painting

figure;

hold;

for i=Head

plot(F(t,P(:,2*i-1),c),F(t,P(:,2*i),s),'LineWidth',10);

end

axis([-25 25 -15 20]);

figure;

hold;

for i=Eyes

plot(F(t,P(:,2*i-1),c),F(t,P(:,2*i),s),'LineWidth',10);

end

axis([-25 25 -15 20]);

figure;

hold;

for i=Hoofs

plot(F(t,P(:,2*i-1),c),F(t,P(:,2*i),s),'LineWidth',10);

end

axis([-25 25 -15 20]);

figure;

hold;

for i=Body

plot(F(t,P(:,2*i-1),c),F(t,P(:,2*i),s),'LineWidth',10);

end

axis([-25 25 -15 20]);

figure;

hold;

for i=Crown

plot(F(t,P(:,2*i-1),c),F(t,P(:,2*i),s),'LineWidth',10);

end

axis([-25 25 -15 20]);

figure;

hold;

for i=Tail

plot(F(t,P(:,2*i-1),c),F(t,P(:,2*i),s),'LineWidth',10);

end

axis([-25 25 -15 20]);

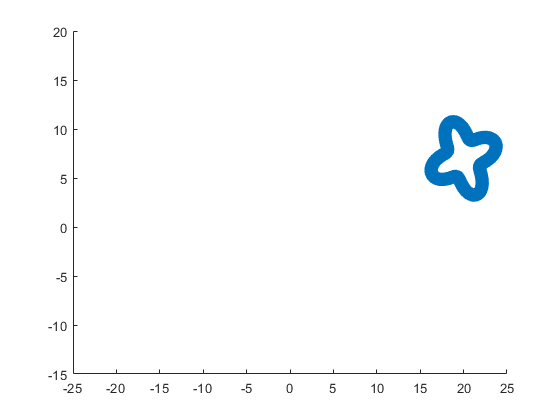

The parameters  ,

,  ,

,  ,

,  ,

,  , and

, and  are written in the different submatrices of the matrix P. The code generates the following curves to illustrate the different parts of our sheep.

are written in the different submatrices of the matrix P. The code generates the following curves to illustrate the different parts of our sheep.

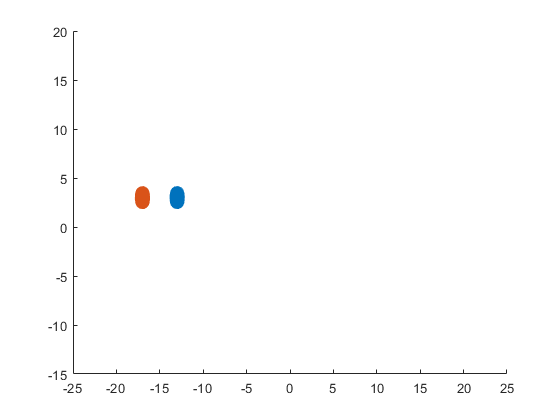

The following ellipse describes the head of the sheep.

The following submatrix of the matrix P represents its parameters.

The parametric equations of the head are the following:

The following ellipses describe the eyes of the sheep.

The following submatrices of the matrix P represent their parameters.

The parametric equations of the left and right eyes correspondingly are the following:

The following ellipses describe the hoofs of the sheep.

The following submatrices of the matrix P represent their parameters.

The parametric equations of the right front, left front, right hind, and left hind hoofs correspondingly are the following:

The following ellipse combined with the rose describes the crown of the sheep.

The following submatrix of the matrix P represents its parameters.

The parametric equations of the crown are the following:

The following ellipse combined with the rose describes the body of the sheep.

The following submatrix of the matrix P represents its parameters.

The parametric equations of the body are the following:

The following ellipse combined with the rose describes the tail of the sheep.

The following submatrix of the matrix P represents its parameters.

The parametric equations of the tail are the following:

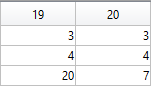

Now all the parts of our sheep should be put together! It is very easy because all the parts are described by the same equations with different parameters.

The following code helps us to accomplish this goal and ultimately draw a Happy Sheep in MATLAB!

% Happy Sheep!

% By Victoria A. Sablina

% Handles

s=@sin;

c=@cos;

% Ellipse + Rose

F=@(t,a,f) a(1)*f(t)+s(a(2)*t).*f(t)+a(3);

% Angles

t=0:.1:7;

% Parameters

% Head (1:2)

% Eyes (3:6)

% Hoofs (7:14)

% Crown (15:16)

% Body (17:18)

% Tail (19:20)

G=-13;

P=[5 7 repmat([.1 .5],1,6) 6 4 14 9 3 3;zeros(1,14) 8 8 12 12 4 4;...

-15 2 G 3 -17 3 -3 G 0 G 9 G 12 G -15 12 4 3 20 7];

% Painting

hold;

for i=1:10

plot(F(t,P(:,2*i-1),c),F(t,P(:,2*i),s),'LineWidth',10);

end

This code is even more compact than the original code from the contest. It is only 253 instead of 280 characters long and generates the same Happy Sheep!

Our sheep is happy, because of becoming famous in the MATLAB community, a star!

Congratulations! Now you know how to draw a Happy Sheep in MATLAB!

Thank you for reading!

MATLAB O/X Quiz

Answer BEFORE Googling!

- An infinite loop can be made using "for".

- "A == A" is always true.

- "round(2.5)" is 3.

- "round(-0.5)" is 0.

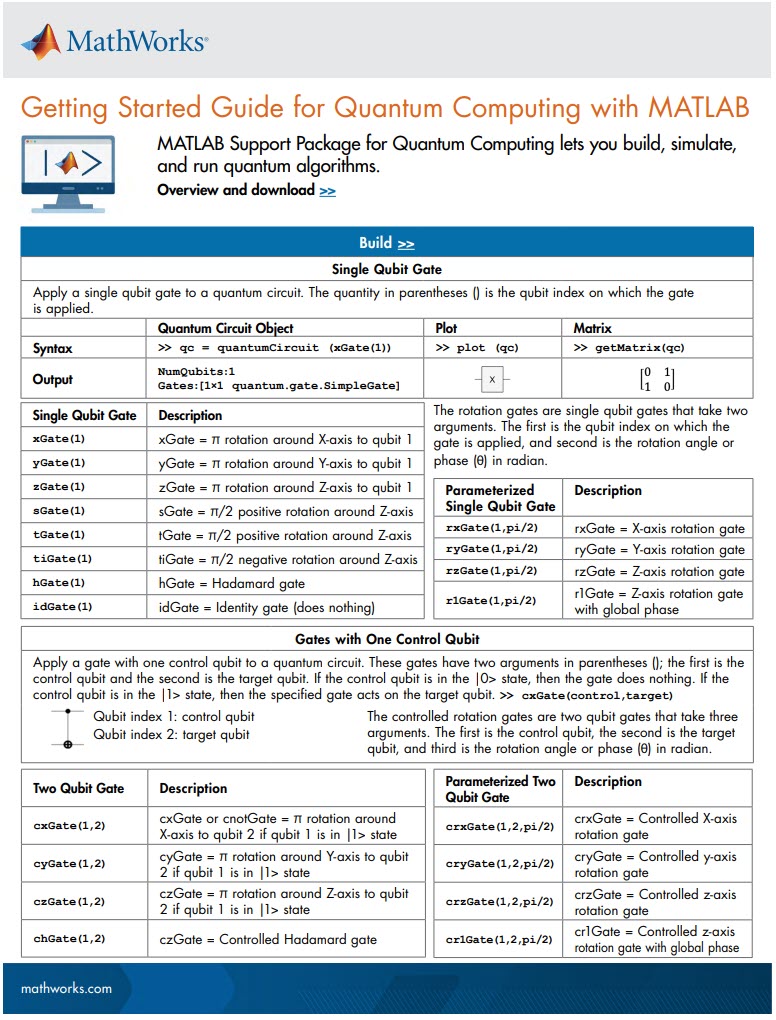

MATLAB Support Package for Quantum Computing lets you build, simulate, and run quantum algorithms.

Check out the Cheat Sheet here!

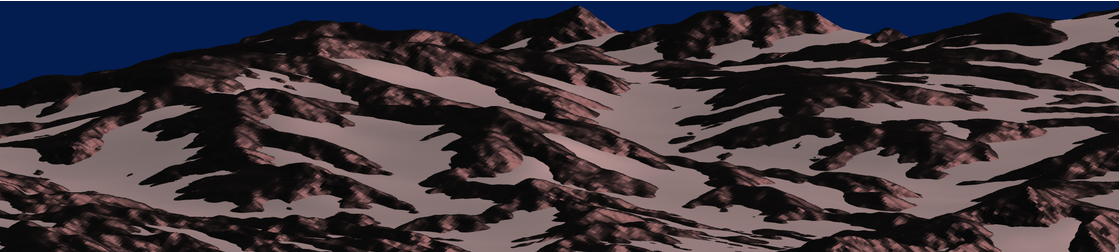

I think that MATLAB's Flipbook Mini Hack had quite some inspiring entries. My work largely deals with digital elevation models (DEMs). Hence I really liked the random renderings of landscapes, in particular this one written by Tim which inspired me to adopt the code and apply to the example data that comes with my software TopoToolbox. The results and code are shown here.

and immeditaely everyone wanted the code! It turns out that this is the result of my remix of @Zhaoxu Liu / slandarer's entry on the MATLAB Flipbook Mini Hack.

I pointed people to the Flipbook entry but, of course, that just gave the code to render a single frame and people wanted the full code to render the animated gif. That way, they could make personalised versions

I just published a blog post that gives the code used by the team behind the Mini Hack to produce the animated .gifs https://blogs.mathworks.com/matlab/2024/02/16/producing-animated-gifs-from-matlab-flipbook-mini-hack-entries/

Thanks again to @Zhaoxu Liu / slandarer for a great entry that seems like it will live for a long time :)

Producing animated gifs from MATLAB Flipbook Mini Hack entries

On Valentine's day, the MathWorks linkedIn channel posted this animated gifThe obvious question was duly asked

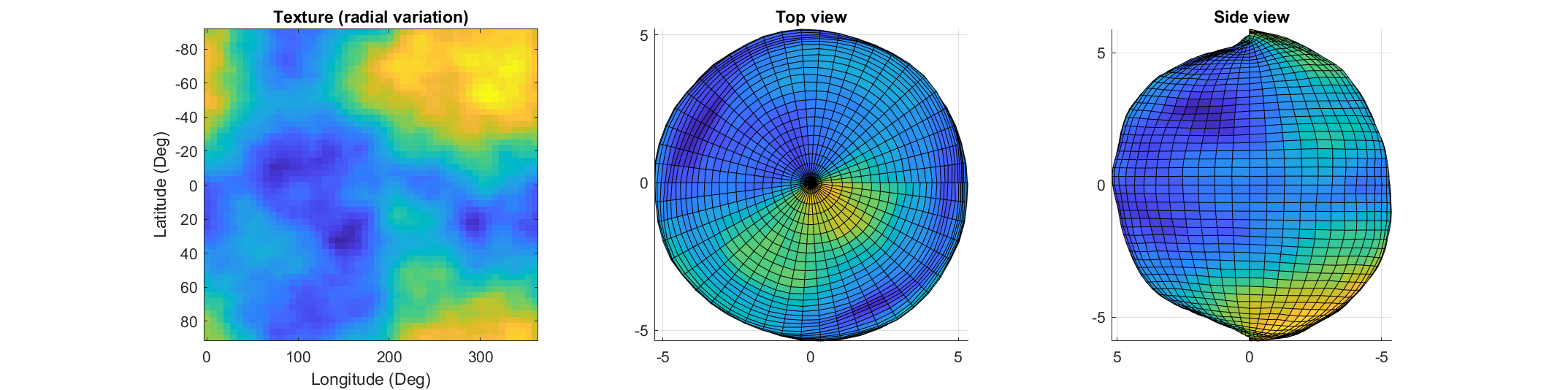

If you've dabbled in "procedural generation," (algorithmically generating natural features), you may have come across the problem of sphere texturing. How to seamlessly texture a sphere is not immediately obvious. Watch what happens, for example, if you try adding power law noise to an evenly sampled grid of spherical angle coordinates (i.e. a "UV sphere" in Blender-speak):

% Example: how [not] to texture a sphere:

rng(2, 'twister'); % Make what I have here repeatable for you

% Make our radial noise, mapped onto an equal spaced longitude and latitude

% grid.

N = 51;

b = linspace(-1, 1, N).^2;

r = abs(ifft2(exp(6i*rand(N))./(b'+b+1e-5))); % Power law noise

r = rescale(r, 0, 1) + 5;

[lon, lat] = meshgrid(linspace(0, 2*pi, N), linspace(-pi/2, pi/2, N));

[x2, y2, z2] = sph2cart(lon, lat, r);

r2d = @(x)x*180/pi;

% Radial surface texture

subplot(1, 3, 1);

imagesc(r, 'Xdata', r2d(lon(1,:)), 'Ydata', r2d(lat(:, 1)));

xlabel('Longitude (Deg)');

ylabel('Latitude (Deg)');

title('Texture (radial variation)');

% View from z axis

subplot(1, 3, 2);

surf(x2, y2, z2, r);

axis equal

view([0, 90]);

title('Top view');

% Side view

subplot(1, 3, 3);

surf(x2, y2, z2, r);

axis equal

view([-90, 0]);

title('Side view');

The created surface shows "pinching" at the poles due to different radial values mapping to the same location. Furthermore, the noise statistics change based on the density of the sampling on the surface.

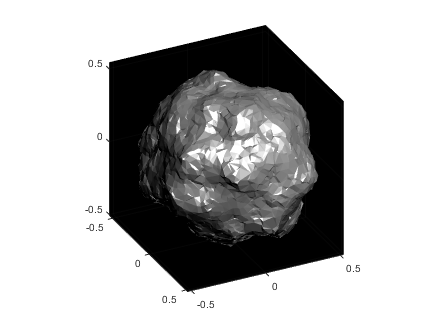

How can this be avoided? One standard method is to create a textured volume and sample the volume at points on a sphere. Code for doing this is quite simple:

rng default % Make our noise realization repeatable

% Create our 3D power-law noise

N = 201;

b = linspace(-1, 1, N);

[x3, y3, z3] = meshgrid(b, b, b);

b3 = x3.^2 + y3.^2 + z3.^2;

r = abs(ifftn(ifftshift(exp(6i*randn(size(b3)))./(b3.^1.2 + 1e-6))));

% Modify it - make it more interesting

r = rescale(r);

r = r./(abs(r - 0.5) + .1);

% Sample on a sphere

[x, y, z] = sphere(500);

% Plot

ir = interp3(x3, y3, z3, r, x, y, z, 'linear', 0);

surf(x, y, z, ir);

shading flat

axis equal off

set(gcf, 'color', 'k');

colormap(gray);

The result of evaluating this code is a seamless, textured sphere with no discontinuities at the poles or variation in the spatial statistics of the noise texture:

But what if you want to smooth it or perform some other local texture modification? Smoothing the volume and resampling is not equivalent to smoothing the surficial features shown on the map above.

A more flexible alternative is to treat the samples on the sphere surface as a set of interconnected nodes that are influenced by adjacent values. Using this approach we can start by defining the set of nodes on a sphere surface. These can be sampled almost arbitrarily, though the noise statistics will vary depending on the sampling strategy.

One noise realisation I find attractive can be had by randomly sampling a sphere. Normalizing a point in N-dimensional space by its 2-norm projects it to the surface of an N-dimensional unit sphere, so randomly sampling a sphere can be done very easily using randn() and vecnorm():

N = 5e3; % Number of nodes on our sphere

g=randn(3,N); % Random 3D points around origin

p=g./vecnorm(g); % Projected to unit sphere

The next step is to find each point's "neighbors." The first step is to find the convex hull. Since each point is on the sphere, the convex hull will include each point as a vertex in the triangulation:

k=convhull(p');

In the above, k is an N x 3 set of indices where each row represents a unique triangle formed by a triplicate of points on the sphere surface. The vertices of the full set of triangles containing a point describe the list of neighbors to that point.

What we want now is a large, sparse symmetric matrix where the indices of the columns & rows represent the indices of the points on the sphere and the nth row (and/or column) contains non-zero entries at the indices corresponding to the neighbors of the nth point.

How to do this? You could set up a tiresome nested for-loop searching for all rows (triangles) in k that contain some index n, or you could directly index via:

c=@(x)sparse(k(:,x)*[1,1,1],k,1,N,N);

t=c(1)|c(2)|c(3);

The result is the desired sparse connectivity matrix: a matrix with non-zero entries defining neighboring points.

So how do we create a textured sphere with this connectivity matrix? We will use it to form a set of equations that, when combined with the concept of "regularization," will allow us to determine the properties of the randomness on the surface. Our regularizer will penalize the difference of the radial distance of a point and the average of its neighbors. To do this we replace the main diagonal with the negative of the sum of the off-diagonal components so that the rows and columns are zero-mean. This can be done via:

w=spdiags(-sum(t,2)+1,0,double(t));

Now we invoke a bit of linear algebra. Pretend x is an N-length vector representing the radial distance of each point on our sphere with the noise realization we desire. Y will be an N-length vector of "observations" we are going to generate randomly, in this case using a uniform distribution (because it has a bias and we want a non-zero average radius, but you can play around with different distributions than uniform to get different effects):

Y=rand(N,1);

and A is going to be our "transformation" matrix mapping x to our noisy observations:

Ax = Y

In this case both x and Y are N length vectors and A is just the identity matrix:

A = speye(N);

Y, however, doesn't create the noise realization we want. So in the equation above, when solving for x we are going to introduce a regularizer which is going to penalize unwanted behavior of x by some amount. That behavior is defined by the point-neighbor radial differences represented in matrix w. Our estimate of x can then be found using one of my favorite Matlab assets, the "\" operator:

smoothness = 10; % Smoothness penalty: higher is smoother

x = (A+smoothness*w'*w)\Y; % Solving for radii

The vector x now contains the radii with the specified noise realization for the sphere which can be created simply by multiplying x by p and plotting using trisurf:

p2 = p.*x';

trisurf(k,p2(1,:),p2(2,:),p2(3,:),'FaceC', 'w', 'EdgeC', 'none','AmbientS',0,'DiffuseS',0.6,'SpecularS',1);

light;

set(gca, 'color', 'k');

axis equal

The following images show what happens as you change the smoothness parameter using values [.1, 1, 10, 100] (left to right):

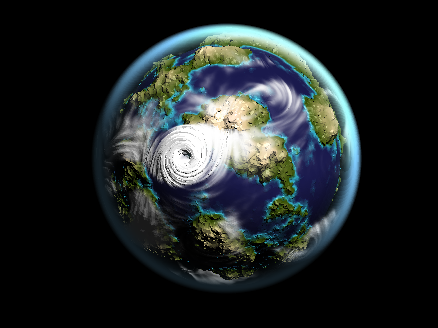

Now you know a couple ways to make a textured sphere: that's the starting point for having a lot of fun with basic procedural planet, moon, or astroid generation! Here's some examples of things you can create based on these general ideas:

The MATLAB command window isn't just for commands and outputs—it can also host interactive hyperlinks. These can serve as powerful shortcuts, enhancing the feedback you provide during code execution. Here are some hyperlinks I frequently use in fprintf statements, warnings, or error messages.

1. Open a website.

msg = "Could not download data from website.";

url = "https://blogs.mathworks.com/graphics-and-apps/";

hypertext = "Go to website"

fprintf(1,'%s <a href="matlab: web(''%s'') ">%s</a>\n',msg,url,hypertext);

Could not download data from website. Go to website

2. Open a folder in file explorer (Windows)

msg = "File saved to current directory.";

directory = cd();

hypertext = "[Open directory]";

fprintf(1,'%s <a href="matlab: winopen(''%s'') ">%s</a>\n',msg,directory,hypertext)

File saved to current directory. [Open directory]

3. Open a document (Windows)

msg = "Created database.csv.";

filepath = fullfile(cd,'database.csv');

hypertext = "[Open file]";

fprintf(1,'%s <a href="matlab: winopen(''%s'') ">%s</a>\n',msg,filepath,hypertext)

Created database.csv. [Open file]

4. Open an m-file and go to a specific line

msg = 'Go to';

file = 'streamline.m';

line = 51;

fprintf(1,'%s <a href="matlab: matlab.desktop.editor.openAndGoToLine(which(''%s''), %d); ">%s line %d</a>', msg, file, line, file, line);

Go to streamline.m line 51

5. Display more text

msg = 'Incomplete data detected.';

extendedInfo = '\tFilename: m32c4r28\n\tDate: 12/20/2014\n\tElectrode: (3,7)\n\tDepth: ???\n';

hypertext = '[Click for more info]';

warning('%s <a href="matlab: fprintf(''%s'') ">%s</a>', msg,extendedInfo,hypertext);

<click>

- Filename: m32c4r28

- Date: 12/20/2014

- Electrode: (3,7)

- Depth: ???

6. Run a function

Similarly, you can also add hyperlinks in figures and apps

And what do you do for Valentine's Day?

which technical support should I contact/ask for the published Simscape example?